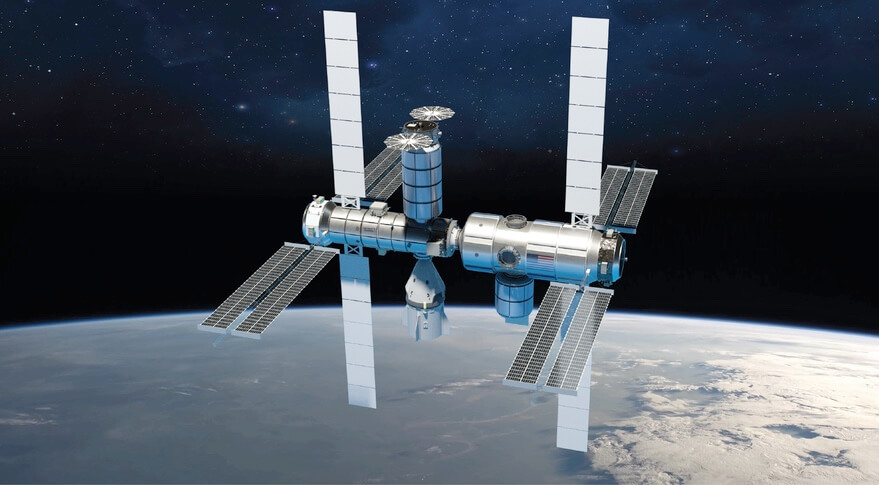

ISS transition to commercial stations poses challenges for partners (Image Credit: SNN)

WASHINGTON — NASA’s plans to shift from the International Space Station to commercial space stations may force one key partner to rethink how it cooperates in low Earth orbit.

Speaking at a panel on space diplomacy organized by George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute Feb. 23, Sylvie Espinasse, head of the European Space Agency’s Washington office, said the current arrangements between ISS partners to barter resources won’t work well on future commercial stations in low Earth orbit.

“ESA-NASA cooperation on the ISS is based on non-exchange of funds and barter of goods and services between the partners,” she said. “This allows ESA to use its asset in orbit, the Columbus module, and to fly its European astronauts.”

Once NASA shifts to commercial stations, though, “ESA will probably not be in a position to buy commercial services from U.S. providers for its research activities in LEO or to fly its astronauts,” she warned. “This will probably not be acceptable for our member states.” Buying services from U.S. companies, she explained, would contradict an ESA mandate to support Europe’s space industry.

ESA doesn’t have a formal plan for operations in LEO after the ISS is retired in 2030 but Espinasse said there were several possible options if the agency can’t buy services directly from American companies. One would be for NASA to be an intermediary, buying services from commercial stations and then bartering with ESA as it does today on the ISS.

“NASA becomes a broker between ESA and U.S. providers,” she said. “But I don’t think this kind of solution can be a long-term solution. It’s too complex.”

A long-term solution, she said, needs to involve some common interest among the partners. “In the case of Europe and ESA, we will have to find our own way to low Earth orbit with our industry,” she said. That could involve a “fully European” solution for a commercial station or industrial partnerships that include American and European companies that jointly operate a station.

An example of such a partnership she cited is cooperation between Northrop Grumman and Thales Alenia Space on the Cygnus spacecraft, developed by Northrop but using major components built by Thales. “This could be beneficial for European industry, participating in these consortia, and may be acceptable for our member states.” Notably, Northrop is one of three companies that won NASA Commercial LEO Destination (CLD) awards in December, proposing a station that leverages its work on the Cygnus spacecraft.

NASA’s own ISS transition plan, published in January, envisioned a role for current ISS partners on commercial space stations but offered few details about how future arrangements would work.

“Each Partner is currently working to identify its needs in LEO through and beyond the ISS, and all have expressed interest in the expansion of commercial uses of LEO,” the document states. “It is NASA’s intention to ensure continued collaboration with Partners on a U.S. CLD through government-to-government, government- to-industry, or industry-to-industry arrangements.”

“NASA is evaluating the capabilities and desires of the existing ISS Partnership, as well as new entrants to the space field, to partner in continuing LEO operations post-ISS,” the report added, including talks with partners on their “interest in capabilities on U.S. CLDs to include their potential requirements in the Agency’s forward planning.”

ESA, meanwhile, has started what Espinasse called “an internal reflection on post-ISS and how to fulfill European needs in LEO.” At a Feb. 16 European space summit, ESA announced it would create a “high-level advisory group” to examine options for European human spaceflight, with an interim report due before ESA’s next ministerial meeting in November. “We will see where this leads us in the coming months,” she said.

She added that the ISS partnership model should work well on exploration efforts like the NASA-led lunar Gateway, where ESA, the Canadian Space Agency and the Japanese space agency JAXA are all contributing components in exchange for flying astronauts to the moon. “There, the model of cooperation with the partners — CSA, JAXA and ESA — is quite similar to the one on the ISS,” she said. Lunar surface operations, she added, could enable additional partnership opportunities for those agencies and others.

“I do not see one model of cooperation in the future, something as monolithic as the ISS,” she concluded, “but rather different models tailored on the common objectives, requirements and priorities of the various partners.”

– Advertisement –