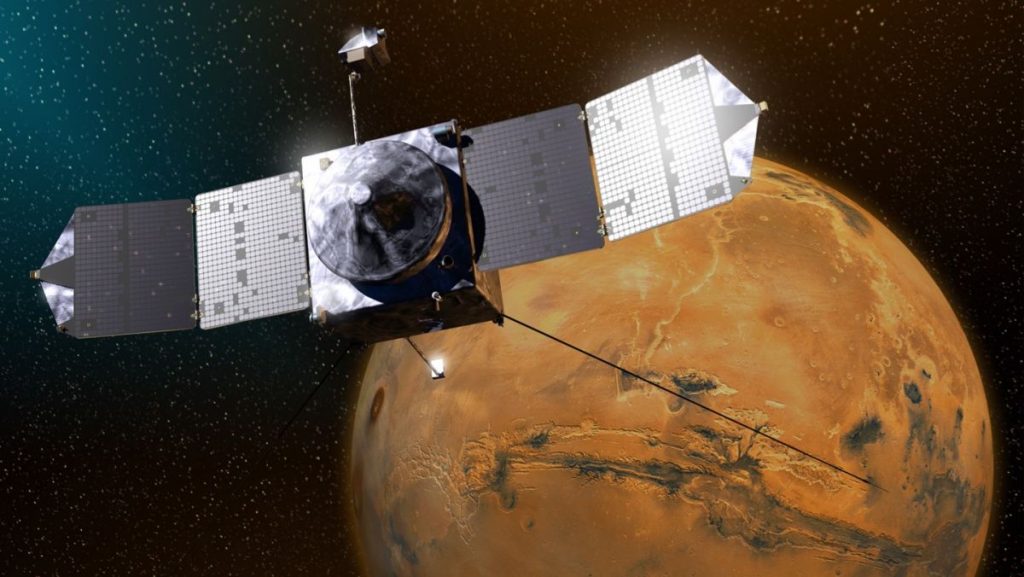

NASA’s Mars MAVEN spacecraft spent 3 months on the brink of disaster (Image Credit: Space.com)

A daunting, three-hour presentation to NASA leadership about the MAVEN Mars orbiter’s future was supposed to be the biggest challenge for the mission team early this year. But just as the presentation was going smoothly on Earth, the spacecraft itself was in serious trouble millions of miles away.

As she finished leading the presentation on that February day, Shannon Curry, recently appointed principal investigator for the MAVEN mission, felt confident about the team’s work making the case that the Mars mission should continue at least three more years, an argument based on six months of exhaustive work from the team.

Then her phone rang. “We finally finish the presentation, I turn everything back on, and our project manager calls me immediately,” Curry told Space.com. “Now, I’m thinking he’s calling me to be like, ‘Congratulations, you did it, you’re doing great,’ and he was like, ‘We’re in safe mode.'”

Related: The boldest Mars missions in history

Safe mode means that a spacecraft has run into a problem it can’t solve on its own, so it has shut down everything it doesn’t need to survive until engineers on Earth can assess the situation. Sometimes, the solution is simple, the cosmic equivalent of rebooting an internet router.

But not this time.

“The safe mode event was — catastrophic is too strong, but I mean, we did get close to losing the spacecraft,” Curry said, calling the incident “incredibly serious” and “scary.” And when the team wanted to be celebrating the end of the six-month mission extension campaign, the timing stung. “It was like getting the wind knocked out of you. On your birthday.”

MAVEN, more formally known as Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution, arrived in orbit around the Red Planet in 2014. Since then, the spacecraft has not only studied the Martian atmosphere, as its name promises, but has also acted as a key relay station for communications between NASA and its Martian landers and rovers, which cannot directly signal Earth.

It’s not a mission that NASA wants to end, and indeed, at the end of the review process that culminated in the grueling presentation, the agency authorized the mission to continue work for three more years. However, MAVEN has spent more than eight years in space, far longer than it was initially designed for, and one particular part is giving the team trouble.

The spacecraft carries two of what engineers call inertial measurement units, or IMUs: one primary version, dubbed IMU-1, and an identical backup called IMU-2. Whichever IMU the spacecraft is using at any given time is responsible for keeping MAVEN in the right attitude, or orientation in space. (Attitude is crucial: functions like charging solar panels and communicating with Earth can’t occur properly when a spacecraft loses attitude.)

After worrying IMU-1 issues cropped up in late 2017, the MAVEN team switched the spacecraft to its backup unit. But late last year, the team noticed that the IMU-2 unit was starting to, essentially, wear out much faster than expected. So in early February, the team returned the spacecraft to its original IMU-1 unit.

Two weeks later, on Feb. 22, the very day of MAVEN’s mission extension presentation, the spacecraft suddenly couldn’t seem to use either IMU to properly position itself.

“For different reasons, both of our [IMU]s started showing problems,” Curry said. “When we went into safe mode, it was because one of them really crashed, basically, and then the other just was losing lifetime.”

The first challenge was to stabilize the spacecraft, which required a procedure engineers call heartbeat termination.

The term “is not just for dramatic effect: basically, it’s like ripping the cord out of the wall,” Curry said. “The spacecraft rebooted its main onboard computer, and then when that didn’t work, it had to swap to the backup computer, and we’ve never been on the backup computer before.”

After more than an hour of the spacecraft trying to revive IMU-1, the computer swap, which also put MAVEN on IMU-2, held. And not a moment too soon: the spacecraft’s focus on the sun was beginning to stray, an existential threat in and of itself.

But even once the MAVEN team had addressed the most urgent issues, the situation remained dangerous, since the team knew that using IMU-2 was courting disaster. “We’ve got one IMU left, and we don’t have much time on it. At all,” Curry said. “We recovered from the safe mode, and then we were still in pretty hot water.”

Race to navigate by the stars

So the team set to work developing what spacecraft managers call “all-stellar mode.” That mode allows the spacecraft to determine its attitude by matching the stars it sees with its internal map of the cosmos. It’s not quite as precise as using an IMU, but it doesn’t have a limited lifetime. Unfortunately, all-stellar mode takes time to develop. The MAVEN team had intended to do that work later this year. “We already had it bookmarked for October as a ‘just in case,’ thinking we were, like, doing our extra credit homework,” Curry said.

The spacecraft had other ideas. Once MAVEN was stable on IMU-2, the team scrambled to develop all-stellar mode as quickly as possible, completing the process in time to send the relevant commands to the spacecraft on April 19, just shy of two months after the crisis began.

For about a month after all-stellar was implemented, the MAVEN team gradually began to turn on and check instruments, although the spacecraft had to remain pointing to Earth throughout the time, limiting the science the mission could do.

Curry especially regrets the loss of data from MAVEN’s extreme ultraviolet instrument, which can’t observe at all when the spacecraft is pointing at Earth. Among other work, that instrument can measure certain types of ultraviolet and X-ray radiation from the sun as it arrives at the Red Planet.

And while MAVEN has been recovering, the sun has produced several major flares that the spacecraft has missed. “That’s a real kicker,” she said. “A couple of X-class flares have propagated past Mars and impacted Mars, and MAVEN is the only one who would be able to observe them and has not been able to.”

The slow ramp-up back to full operations also meant that MAVEN spent an extra month unable to serve as a relay satellite for the InSight lander and Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, the three NASA robots currently active on the Martian surface. Although other satellites also participate in this work, MAVEN bears one of the largest loads. So the spacecraft’s three-month outage meant not just reduced science from MAVEN but reduced science from Mars overall.

“It’s been really hard on all of the surface assets,” Curry said. And in turn, the rescue was about more than MAVEN itself. “It wasn’t just simply to make sure we saved our spacecraft. This was enabling a lot of data at Mars in general.”

Back to work

After more than three months out of commission, MAVEN finally returned to its normal operations on Saturday (May 28), according to a statement from the University of Colorado Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, where the mission is headquartered. But the milestone doesn’t mean the spacecraft team’s work is done.

Although all-stellar mode can do the job for normal operations, it isn’t precise enough to see MAVEN safely through its most delicate maneuvers, and the spacecraft still has precious little time left on its IMUs.

“We have to spend this summer and the next year or two coming up with very clever ways to stop using the IMU when we normally would,” Curry said. “If we did nothing, we would not make it the next 10 years.” (The recent mission extension sees the spacecraft through 2025, but NASA has said it wants to use MAVEN’s relay capability during its planned Mars sample-return mission campaign, which is currently targeting delivery at Earth in 2033.)

Curry said she’s confident the MAVEN team can tackle this challenge as well. “When all of a sudden, you’re faced with this, frankly, existential threat of saying, ‘Figure it out or you’re gonna lose the spacecraft,’ people figure it out. And so we have a path forward, we have a bunch of ideas to start testing,” she said. “Is everything ironed out? No. It’s going to take a lot more work to iron out some clever ways to do that. But again, this is a very, very, very creative and smart team.”

In the meantime, now that MAVEN is back to normal operations, there’s precious science to be done regarding Mars’ atmosphere. In particular, Curry is excited to see upcoming data that will show how the atmosphere responds to the sun’s increasing activity. The sun’s activity fluctuates over an 11-year solar cycle, with the star on an upswing now that scientists expect will peak around 2025.

“The solar cycle is just cranking right now and we’re still at least 18 months off the peak, so we could not be more excited to get back up and running in full,” Curry said.

And the 2025 solar maximum is particularly intriguing because scientists expect it will coincide with the Red Planet’s next serious dust-storm season. During the southern hemisphere’s summer, weather conditions can trigger dust storms so large that some encompass the entire planet. It’s dust-storm season on Mars now and MAVEN has watched previous seasons as well, but the alignment of cycles ups the stakes.

“MAVEN will be observing the most extreme conditions it ever has, because there’ll be dust, so it’s a driver from below, and then extreme solar activity as a driver from above,” Curry said of the tantalizing 2025 opportunity. “We are anxious just to get back into it.”

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.