X-class Halloween solar flare erupts from sun, causes radio blackouts (video) (Image Credit: Space.com)

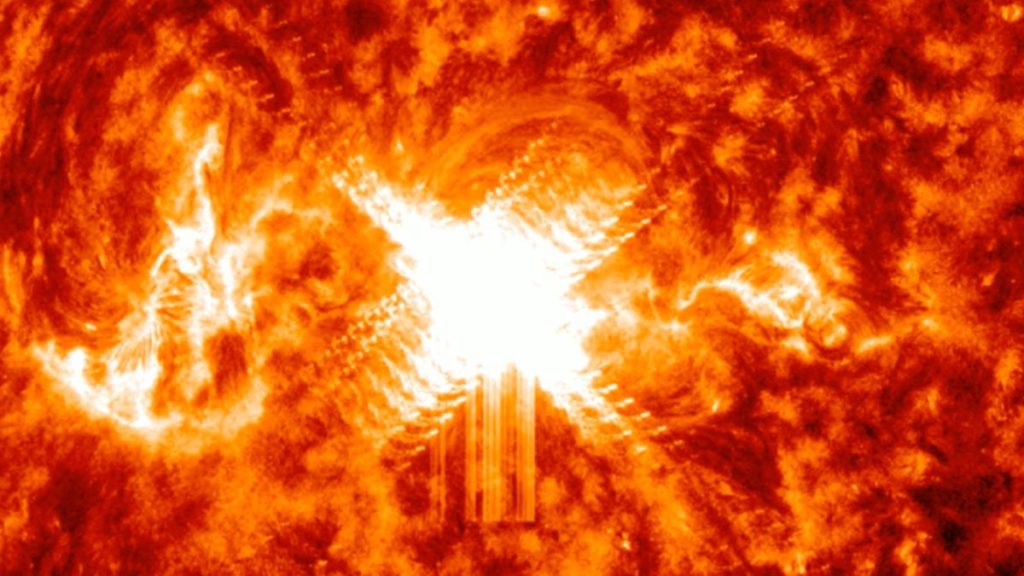

The sun put on quite the spooktacular show on Halloween, firing off an X2.0 solar flare.

A sunspot known as AR 3878 fired off the X-class flare at 5:20 p.m. EDT (2120 UTC) on Oct. 31, measuring in at X2.0. Sunspots are dark, planet-size areas on the sun where strong magnetic fields from within our star well up to the surface.

According to Spaceweather.com, a coronal mass ejection (CME) was not produced from the solar flare, which removes the chance for a geomagnetic storm to impact Earth and potentially create auroras, also known as the northern lights or aurora borealis. CMEs are composed of plumes of plasma and magnetic field from the sun and can accompany a solar flare, radiating out from the blast into space and reaching Earth.

VIDEO NOT PLAYING?

Some ad blockers can disable our video player.

X-class flares are the most powerful type on the 4-level classification scale, measuring ten times more powerful than the next class down, M-class. Following each letter classification is a number (2.0 in this case) that denotes each flare’s relative strength.

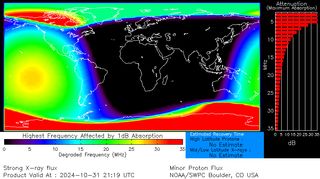

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) reported that the flare was powerful enough to reach a R3-Strong level on its Space Weather Scale for radio blackouts, which focuses on what type of impacts solar flares have on Earth. With the large amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation released, a shortwave radio blackout was reported to follow the blast and impact signals across parts of the Pacific Ocean.

For many, the question remains: will this flare follow with an opportunity to see the aurora in the coming days? As always, it all depends on whether or not a CME accompanies the flare and is headed in our direction — which did not happen in this case.

This phenomenon is what causes auroras, the mesmerizing light shows created in the night sky when CMEs interact with Earth’s magnetic field, which funnels charged particles towards the poles. That’s why we most commonly see auroras near the poles — the aurora borealis at the north pole, and the aurora australis at the south pole.

To determine if a CME was released and is headed in Earth’s direction, scientists rely on imagery captured by a coronagraph aboard National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft.

Even though we will not get a chance to view the Northern Lights this time, SWPC forecasters say there’s a chance for additional strong solar flares through the end of the weekend (Nov. 3). According to the forecast discussion, SWPC is expecting more M-class flares with still the possibility for X-class flares to erupt from the sun in the coming days.