Why I’m going to Easter Island for the ‘ring of fire’ annular solar eclipse (Image Credit: Space.com)

Would you travel 8,467 miles to see a ring around the moon for less than six minutes?

On Oct. 2, 2024, a few hundred eclipse chasers will be on the volcanic Easter Island — called Rapa Nui by natives and one of the most remote places on Earth — to witness an annular solar eclipse.

I’ll be one of them, reporting for Space.com while embedded with AstroTrails.

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of “A Stargazing Program For Beginners” and “A traveler’s guide to total solar eclipses 2026-2034,” he is also a senior contributor at Forbes.

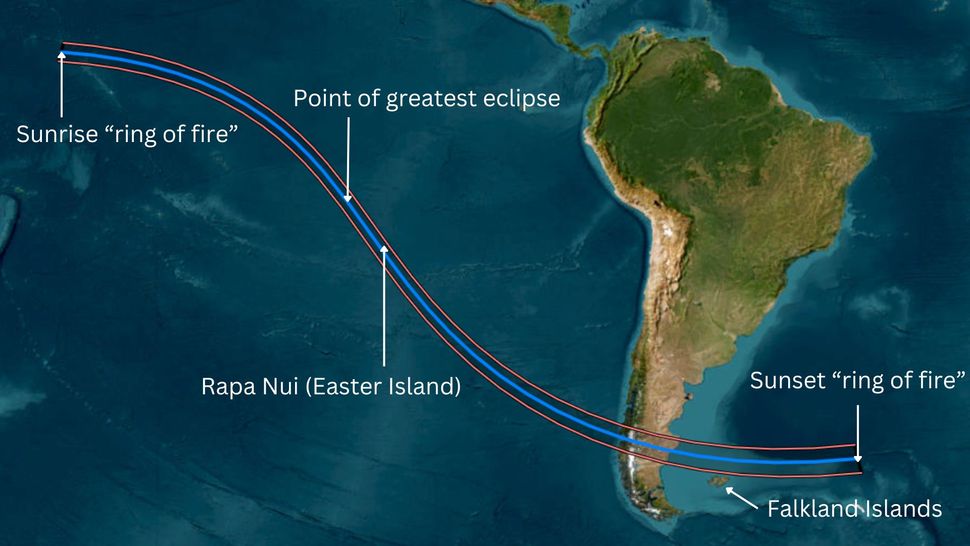

At around 14:04 Easter Island Summer Time, a new moon will nudge across the sun’s disk, making an 87% partially eclipsed crescent into a “ring of fire” for about 5 minutes and 50 seconds.

It will take place exactly one lunar year after Oct. 14, 2023’s almost identical event across the southwest U.S. and be the longest annular solar eclipse until Feb. 6, 2027, when a 7 minutes and 51 seconds “ring of fire” will be visible from Chile, Argentina and Uruguay, and at sunset from Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin and Nigeria.

I’ll likely be in Ghana for that one, but there are no prizes for guessing where I’ll be on Oct. 2. This “ring of fire” will also be visible above southern Chile and Argentina, but I’ve had the great privilege of visiting both of those countries already, for total solar eclipses in recent years.

You can follow the eclipse on Space.com’s solar eclipse live blog and watch the action unfold via numerous livestreams. Details of which will be released closer to the time.

Besides, I’ve wanted to visit Easter Island ever since I started writing about astro-tourism and solar eclipses in 2009, when I noticed there was to be a total solar eclipse there on Jul. 11, 2010. I had been clouded out during my only totality on Aug. 11, 1999, in Cornwall, England, at 23, but a lack of funds and ambition had kept it from my bucket list. After interviewing expedition leaders, astronomers and eclipse chasers about their plans to visit Easter Island and writing a few articles for magazines, I was hooked on the concept of eclipse chasing. Unfortunately, I was also broke, and so did what thousands of people now do after every central total solar eclipse — they ask, “When is the next one?” and start saving. Two years later, I sat on the beach in Palm Cove in Queensland, Australia, where watched first a sunrise and then a totally eclipsed sun for 122 mind-blowing seconds.

It was a fork in my road. I had seen the light and began chasing it, barely missing a total solar eclipse since. Sometimes, I went as a reporter, other times as an expedition leader, but always as an eclipse chaser.

It doesn’t matter where you watch an eclipse. Anywhere with a clear sky is the best advice. However, there are some places where the thought of an eclipse sends shivers down spines. On Oct. 14 last year, I traveled to Chaco Canyon in New Mexico to experience that “ring of fire” in a home of ancient solar astronomy. Even experienced eclipse chasers routinely dismiss annulars because you must keep your solar eclipse glasses on. You don’t see the sun‘s corona. There is no darkness, no rush of excitement. That’s what they say. But from Casa Rinconada, home to the most extraordinary ancient kiva — great house — of the ancient sky-watching ancestral Puebelon people, the experience was exquisite. Pre-eclipse, the gathering dusk and dropping temperature were just as strange as any total solar eclipse, and the “ring of fire” was beautiful.

One lunar year later, I’m doing it all over again — and once again in the home of an ancient culture of sky-watchers. Like the ancestral Puebelon, the Rapa Nui were astronomers. There is some evidence that the moai — the 13-foot, 14-ton monoliths of human heads that are now emblems of a vanished civilization — are aligned to the stars. The 15 moai of Ahu Tongariki are believed to be oriented toward the setting of the Pleiades over a nearby hill, while the seven moai at Ahu Akivi are through to watch the point on the horizon where the three stars of Orion’s Belt set.

It may boast some tantalizing alignments, but the island doesn’t get many central solar eclipses. That may seem a shallow claim just over 14 years after a total solar eclipse on the island, but let’s put it in a historical context. The Rapa Nui are thought to have settled on the island as late as 1200 AD, with the moai dating from between 1250 and 1500. During that time, there were a total of zero total solar eclipses. The previous time totality darkened the island was way back on Mar. 30, 591. The Rapa Nui culture may have come and gone between total solar eclipses, but its people may have seen an annular.

Oct. 2’s annular will be the island’s first since Nov. 27, 1788, 66 years after a Dutch crew became the first Europeans to visit it on Easter Sunday. According to Britannica, they described it as a place where people worshiped giant standing statues with fires while they prostrated themselves to the rising sun. There’s zero evidence that a “ring of fire” visible just after sunrise on Sept. 1, 1095, had any particular significance, nor the brief event on Dec. 11, 1433. But it’s an exciting thought.

Related: Eclipse expert Jamie Carter wins media award for extensive solar eclipse coverage

Eclipse chasing is as much about travel, exploration and learning as it is about fleeting astronomical events. It’s a grand excuse to see the world as dictated by nature. Maybe that’s even truer for annulars. As soon as I experienced that profound annularity in Chaco last year, a trip to Easter Island to witness a “ring of fire” in the “Navel of the World” this year began to feel inevitable.

That’s why I’m going to Easter Island for this “ring of fire.” Besides, its next total solar eclipse is in 321 years. This is my last chance.

Editor’s note: This article was made possible with travel from Santiago, Chile supported by a press trip with AstroTrails.