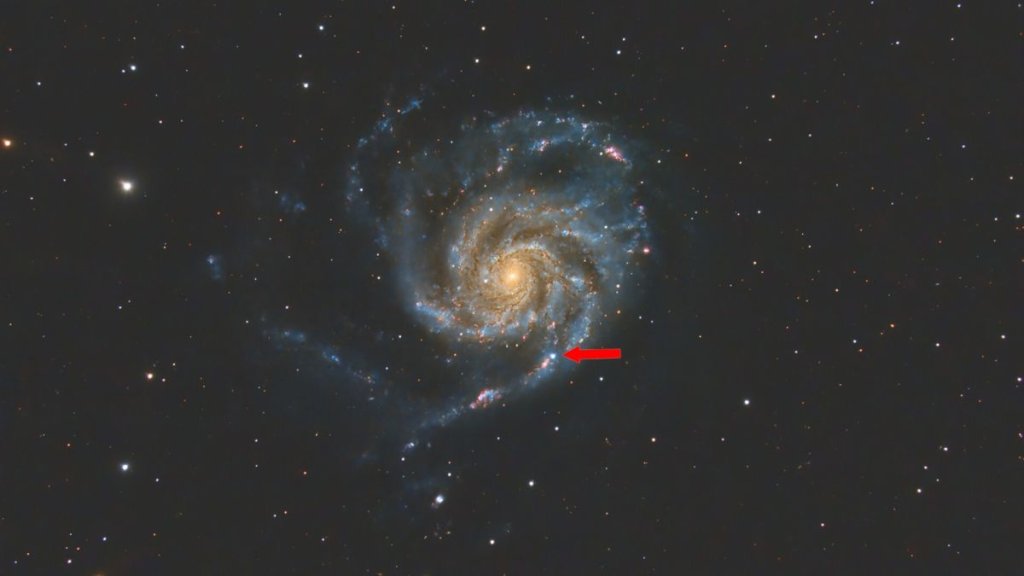

This new supernova, the brightest in years, could help astronomers forecast future star explosions (Image Credit: Space.com)

A new supernova has turned into the most watched phenomenon in the May night sky. The close proximity of the stellar explosion and the vast amount of observations gathered since the discovery promise to advance astronomers’ understanding of stellar evolution and could even lead to major advances in supernova forecasting.

Supernovas are powerful explosions in which very massive stars, at least eight times more massive than our sun, die when they use up all the hydrogen fuel in their cores. The discovery of this latest exploding star, known officially as 2023ifx, was a serendipitous one.

When amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki settled in his amateur observatory in the mountains near Yamagata City in northern Japan on the night of May 19, little did he know that his nightly scan of the nearby galaxies would produce an astronomical sensation. Itagaki, a CEO of a food company, is no novice in the supernova business. In fact, he is one of the world’s most prolific amateur supernova hunters and has over 170 supernova discoveries under his belt, according to Scientific American.

That’s why when Itagaki turned his telescope to the Pinwheel Galaxy, a popular target among amateur astronomers located some 21 million light-years from Earth, it didn’t take long for him to realize that he was witnessing something significant.

Related: This new supernova is the closest to Earth in a decade. It’s visible in the night sky right now.

Since Itagaki reported the observation to the International Astronomical Union that night, the brightening star in the Pinwheel Galaxy has become the most studied object in the night sky. Both the world’s largest scientific telescopes and amateur skywatchers around the globe have turned their lenses toward the freshly exploded star, which has since been declared the nearest supernova explosion in the last five years. The event’s close proximity to Earth is only one part of its scientific appeal.

Daniel Perley, an astrophysicist at Liverpool John Moores University, told Space.com that thanks to the large quantity of available observations of the galaxy taken by both amateurs and professionals, astronomers might be able to pin down the exact moment of the explosion to within minutes.

“Usually, when a supernova is found, it’s already a day, two days, three days, even a week after the explosion when we first see it,” Perley said. “This one was found within hours of the actual initial explosion of the star, and we may even be able to get that down to a few minutes after we collect some of the amateur data that people have been incidentally taking of the galaxy. So it’s going to be possible to get very, very nice constraints on exactly the moment of explosion. And that’s unusual.”

With today’s technology, supernova detections are not rare. According to Cardiff University astrophysicist Cosimo Inserra, powerful survey telescopes find several supernovas every night. Within a single year, more than 22,000 so-called transient events, sudden powerful brightenings in galaxies, can be discovered. This number includes supernovas, but also stars shredded by black holes.

“On average, the distance of the majority of these transients is up to redshift 0.1,” Inserra said. “That’s between 0.7 to 1.5 Giga light-years [a Giga light year equals to a billion light years].”

When such an explosion goes off in the neighborhood of our galaxy, the Milky Way, astronomers can detect it before it reaches its maximum brightness, monitor it for a longer period of time, but also make measurements that are not possible for the more distant explosions.

“When it’s nearby, we can get the entire electromagnetic spectrum of information, which our telescopes usually cannot detect in the far away objects because the signal is so faint,” Inserra said. “The full electromagnetic spectrum has only been detected for a few [supernovas]. And with this one, because it’s so bright, we already have X-ray information, optical and near infrared.”

Different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum — the different wavelengths of radiation emitted by objects in the universe — reveal different types of information about their sources. Inserra hopes that the measurements of supernova 2023ifx will reveal the chemical composition of the material blasted out by the collapsed star. This, in turn, could help advance our understanding of the chemical evolution of the universe, revealing how the dust dispersed from blown-up stars forms future generations of stars throughout the cosmos.

The observations will also improve the understanding of the evolution of stars themselves, particularly the changes they undergo in the final stages of their lives, added Perley.

“The important thing is to understand the nature of the star that exploded,” said Perley. “If we can see if the star had some variable activity before the explosion, that would be a major development.”

According to Inserra, astronomers can tell which stars are in the final stages of their lives but have no way to tell whether the star is going to go supernova in a million years from now or tomorrow.

Astronomers are already scouring data from the Hubble Space Telescope to learn more about the so-called progenitor star that gave rise to 2023ifx.

In the meantime, the stellar explosion that captivated the astronomical community may be reaching its peak brightness. But it will remain visible with backyard telescopes for months to come. Inserra expects that professional astronomers will be studying the event’s aftermath for years.