The Quadrantid meteor shower 2024 peaks tonight alongside a bright moon (Image Credit: Space.com)

Early each January, the Quadrantid meteor stream provides one of the most intense annual meteor displays, with a brief, sharp maximum lasting only a few hours.

The Quadrantid meteor shower actually radiate from the northeast corner of the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman, so we might expect them to be called the “Boötids.” But back in the late-18th century there was a constellation here called “Quadrans Muralis,” the “Mural or Wall Quadrant” (an astronomical instrument). Quadrans Muralis is a long-obsolete star pattern, invented in 1795 by J.J. Lalande to commemorate the instrument used to observe the stars in his catalog.

Adolphe Quetelet of Brussels Observatory discovered the shower in the 1830s, and shortly afterward it was noted by several astronomers in Europe and America. Thus, they were christened “Quadrantids” (pronounced KWA-dran-tids) and even though the constellation from which these meteors appear to radiate no longer exists, the shower’s original moniker continues to this day.

Related: January full moon 2024: The ‘Wolf Moon’ howls at the Gemini twins

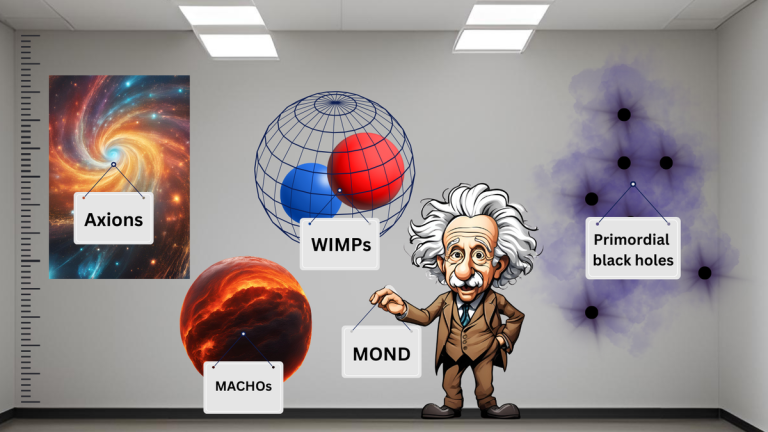

Crumbs of a dead comet?

At greatest activity, 60 to 120 meteor members per hour have been reported. However, the Quadrantid influx is sharply peaked: Six hours before and after maximum, these blue meteors appear at one-half of their highest rates.

So, the stream of particles that produce this shower is a narrow one — apparently derived within the last 500-years from a small comet. The parentage of the Quadrantids had long been a mystery. Then Dr. Peter Jenniskens, an astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., noticed that the orbit of 2003 EH1 — a small asteroid discovered in March 2003 — “falls snug in the shower.” He believes that this 1.2-mile (2 km) chunk of rock is the source of the Quadrantids; possibly this asteroid is the burnt-out core of the lost comet C/1490 Y1.

Yet another celestial body that might also be contributing meteoric material to the Quadrantids is the comet 96P/Machholz.

When and where to look

Looking for a telescope for the next night sky event? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner’s telescope guide.

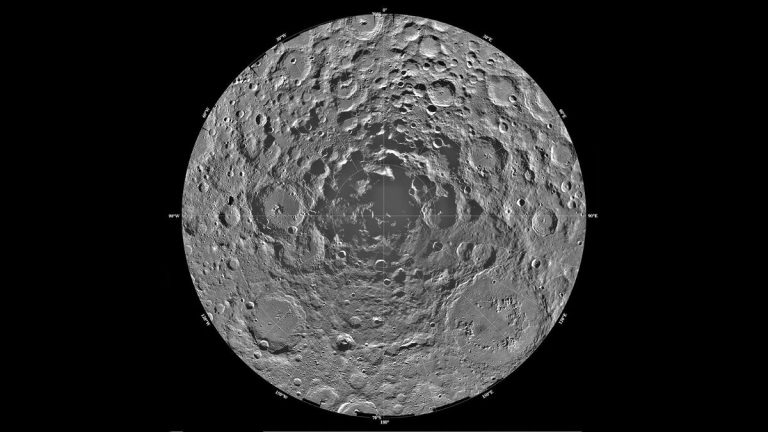

As viewed from mid-northern latitudes, we have to get up before dawn to see the Quadrantids at their best. This is because the radiant — that part of the sky from where the meteors appear to emanate — is down low on the northern horizon until about midnight, rising slowly higher in the northeast as the night progresses. The growing light of dawn ends meteor observing usually by around 6 a.m. So, if the “Quads” are to be seen at all, some part of that six-hour active period must fall between 2 and 6 a.m.

This year will be a favorable year to watch for the peak of this meteor display across much of North America. According to meteor experts, Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the 2024 Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the peak of this year’s shower is predicted for 4 a.m. Eastern Time or 1 a.m. Pacific Time on Thursday, Jan. 4. So, across the contiguous U.S. and southern Canada, maximum activity will arrive as the radiant of the “Quads” is ascending toward a favorable viewing position in the northeast sky. The eastern states hold an advantage as the radiant will be noticeably higher up in the sky as opposed to locations farther to the west.

Under a clear dark sky, meteor rates of 60 or more per hour might be possible for Easterners, while somewhat lower numbers should be expected for those in the Far West.

Moon muscles in

But unfortunately, there’s a stumbling block for prospective meteor watchers this year in the form of the moon. In one out of every three years, bright moonlight hinders the view of this meteor display and this is one of those years.

In 2024, the moon arrives at its last quarter phase about six hours before the peak of the shower. That means that on the morning of Jan. 4, there is going to be a bright half-moon (actually a very wide waning crescent), situated in the constellation Virgo, that will be reaching its highest point in the southern sky just as dawn is breaking. As luck would have it, this particular meteor display is at its best just before the break of dawn — about 6 a.m. local time — when the Quadrantid radiant appears at its highest, about two-thirds of the way up in the northeastern sky.

That means that from midnight to dawn on Thursday morning, Jan. 4, the moon will brighten the sky somewhat, and will probably squelch a fair number of the fainter Quadrantid streaks.

So, factoring the moonlight in, means that if you live in the Eastern U.S., you may not see more than 20 or 30 of these blue streakers during a single hour. Out West, you might catch sight of about a dozen or so Quads per hour.

If you are hoping to catch a look at the stars of the Boötes constellation or any other night sky sight, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you’re looking to snap photos of the Quadrantid meteor shower or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph meteor showers, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Stay warm; “shower” with a friend

Lastly — and I’ve touched on this point many times before, but certainly it should be addressed again: Your local weather will likely be more appropriate for taking in a hot bath as opposed to a meteor shower. And indeed, at this time of year, meteor watching can be a long, cold business. You wait and you wait for meteors to appear and when they don’t appear right away, and if you’re cold and uncomfortable, you’re not going to be looking for meteors for very long! Therefore, make sure you’re warm and comfortable. Warm cocoa or coffee can take the edge off the chill, as well as provide a slight stimulus. It’s even better if you can observe with friends. That way, you can cover more sky.

Good luck and clear skies!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.