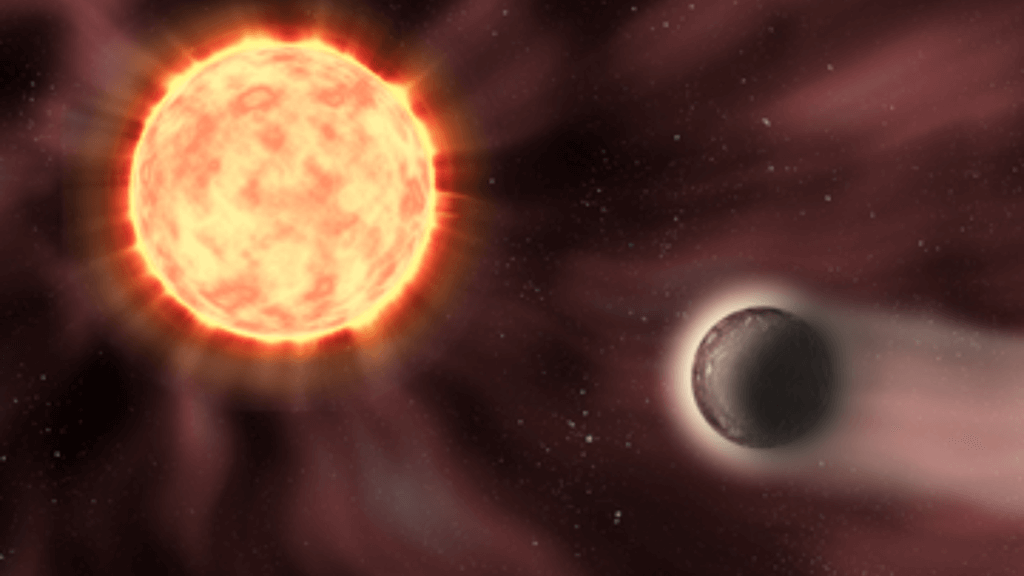

The powerful winds of super magnetic stars could destroy the possibility for life on their exoplanets (Image Credit: Space.com)

Cool stars with powerful magnetic fields could have stellar winds so harsh they strip away the atmospheres of orbiting planets, making these worlds incapable of hosting life.

This finding was the result of simulations led by scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP), and could prove crucial in the quest to find extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, that can sustain life elsewhere in the universe.

The researchers found certain charged particles, which comprise the stellar winds of strongly magnetic cool stars, could reach speeds up to five times greater than the average speed of our sun’s solar wind, which falls around 1 million miles per hour (1.6 million kilometers per hour). This means exoplanets surrounding these stars could be battered by streams of charged particles traveling as fast as 5 million miles per hour (8 million kilometers per hour).

For context, that’s around 6,000 times the speed of a bullet fired by a handgun and enough to destroy the conditions needed to support life on any planets that may be orbiting these stars, including worlds that fall in so-called habitable zones. That’s quite striking as habitable zones are defined as regions in which the temperature is just right to host liquid water and therefore potentially support life as we know it.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope could determine if nearby exoplanet is habitable

Even cool stars can be unfriendly to life

“Cool stars,” as considered by the team, include stellar bodies divided into four categories: F-type, G-type, K-type and M-type stars. These categories are dependent on size, temperature and brightness.

The sun is an average star and an example of a G-type star, for instance, which are larger and brighter than stars in the F-type category. Stars smaller and cooler than the sun fall in the M-type category and are also known as “red dwarfs.” These faint stellar bodies are the Milky Way’s most common stars, but their low light output can make them tough to see.

In addition to light, stars put out stellar winds. These winds, made up of charged particles, inevitably interact with orbiting planets.

An example of such an interaction is with the auroras created over the Earth’s north and south poles. When solar winds strike our planet’s magnetic bubble — the magnetosphere — several processes occur that lead to glowing green patterns in the sky. But the result of stellar wind antics, as it appears, isn’t always so pretty.

While the sun’s solar wind is relatively easy to study, with humanity capable of putting spacecraft like the Solar Orbiter in situ around our star to study charged particles streaming from it, stellar winds emanating from more distant stars are nearly impossible to see directly.

Though astronomers can look at the influence these stellar winds have on thin and wispy gas that exists between stars in the Milky Way to deduce some information, this method can only be applied to a few stars.

That’s why scientists turn to numerical simulations and computer models to better understand stellar winds without requiring direct observation, such as with the recent study.

Working with the supercomputing facilities of the AIP and the Leibniz Rechenzentrum (LRZ), the study team developed a sophisticated model based on the properties of 21 well-observed stars. This marked the first systematic study of stellar winds associated with each of those aforementioned star categories.

This model allowed the scientists to assess how properties like the stars’ gravities, magnetic field strengths and rotation periods affected their stellar wind velocities. It also helped them predict the expected size of the boundary between a star’s corona — its outer atmosphere — and its stellar wind, called the Alfvén surface. That assisted with determining whether planets orbiting a star occasionally enter the Alfvén surface or are completely embedded within it, the latter of which could trigger intense magnetic interactions between a planet and its parent star.

The scientists found that K- and M-type stars, with magnetic fields stronger than that of the sun, have faster stellar winds than our star. That means their planets live in a harsher environment than planets in the solar system. The team also determined that, in terms of stellar winds, conditions around F- and G-types are milder than around M-types like our sun.

Because stellar winds are one of the mechanisms by which stars lose material over time, the team’s new research could also trigger a rethink of the mass-loss process.

And, though this work involved just 21 stars, the results could be general enough to apply to other cool stars. This means the research paves the way for other stellar wind studies and deepen our understanding habitability in the Milky Way.

The team’s research is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.