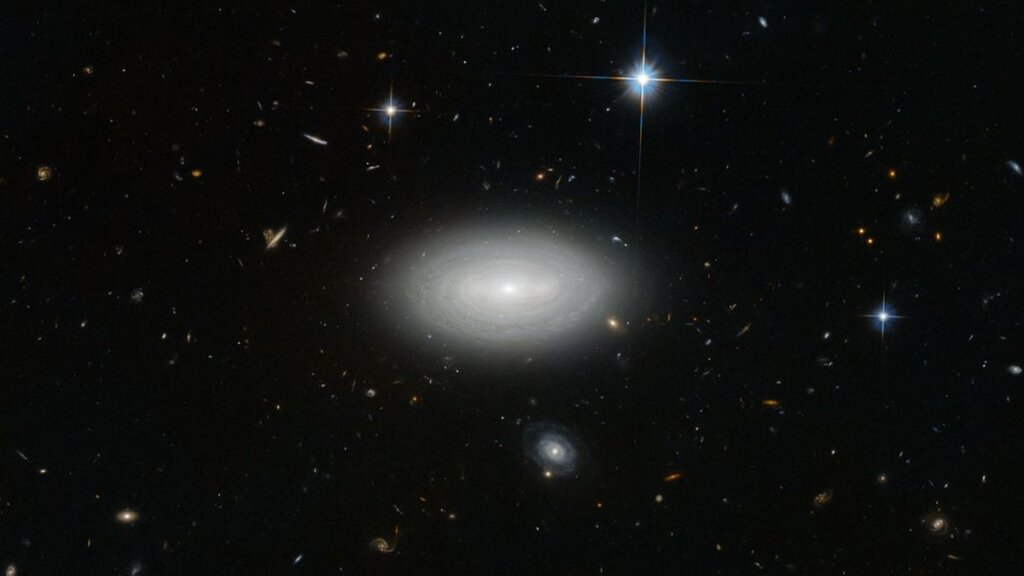

The loneliest monster black holes may also be the hungriest (Image Credit: Space.com)

Supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies in cosmic deserts of the universe, where neighbors are rare and stellar nourishment is scarce, still manage to munch on material more often than their counterparts in more crowded areas of the galaxy, new research suggests.

In the past decade, astronomers have debated whether galaxy mergers — similar to the one underway between the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy — are the main triggers that strip material from galaxies and funnel it to colossal black holes at their centers. New observations, which found over 20,000 “hungry” black holes in lonely slices of the universe known as cosmic voids, show that these invisible beasts “snack” more often when there are fewer interacting neighbors to interrupt them.

“These findings challenge our current understanding of how galaxies evolve,” Anca Constantin, an astrophysics professor at Virginia’s James Madison University who co-led the study, said in a statement.

Related: Black holes: Everything you need to know

Cosmic voids are essentially “3D bubbles of space,” some of which stretch over 500 million light-years across and contain just a handful of galaxies — if any at all. Also called the universe’s wastelands, cosmic voids are thought to make up half of our universe, and together host 20% of its galaxy population.

There is growing evidence that the Milky Way, too, is contained in a spherical void whose radius is at least 1 billion light-years across, which is seven times larger than an average cosmic void. The remaining 80% of galaxies of the universe are birthed in more crowded regions, where anywhere between 50 to 1000 huddle in galaxy clusters, researchers say.

The 80% of galaxies that live in the more populated corners of the universe are huddled close enough to interact gravitationally with each other and eventually merge. During this process, galaxies strip matter from one another, which in turn feeds the supermassive black holes at their centers. However, precisely how the material gets directed into the black hole such that it begins “snacking or munching on that surrounding matter” has been heavily debated, said Anish Aradhey, who just graduated from the Harrisonburg High School in Virginia and co-led the new study, at the American Astronomical Society conference in New Mexico last week.

The merger theory lacks a robust explanation of how black holes grow in galaxies that are friendless in their cosmic neighborhood and thus do not interact with each other, a process thought to be necessary to make stellar food available. So to learn more about how exactly black holes start feeding, Aradhey and his team studied “hungry” supermassive black holes in “the loneliest galaxies in places of the sky called cosmic voids,” he said.

“Galaxies are more able to channel that fuel towards centers of supermassive black holes if they don’t have to compete for that fuel with their neighbors through interactions and stripping and other processes,” said Aradhey.

Using eight years of data collected by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) sky-mapping telescope, Aradhey’s team studied how the brightness of about 290,000 galaxies changed over time, and discovered over 20,000 actively feeding black holes that were hidden in previous searches.

Past surveys on void galaxies focused their searches on optical or mid-infrared wavelengths, the latter of which relied on detected light to categorize the activity within galaxies: The bluer the light, the more intense the star formation, while red light suggests emissions from a hungry black hole feeding on material. However, void galaxies host lots of star formation and thus emit bluer light emissions, which “drown out” the light from feeding black holes within them, thus masking their presence, Aradhey said, which explains why past studies missed them.

Instead, his team studied telltale fluctuations in brightness of infrared light over time that betrayed the presence of feeding black holes, whose activity turned out to be more common in small or midsize galaxies than large ones, the team found.

“The smaller galaxies seem to snack more effectively, if you will, when they are left alone and they don’t interact with their neighbors,” Aradhey said.