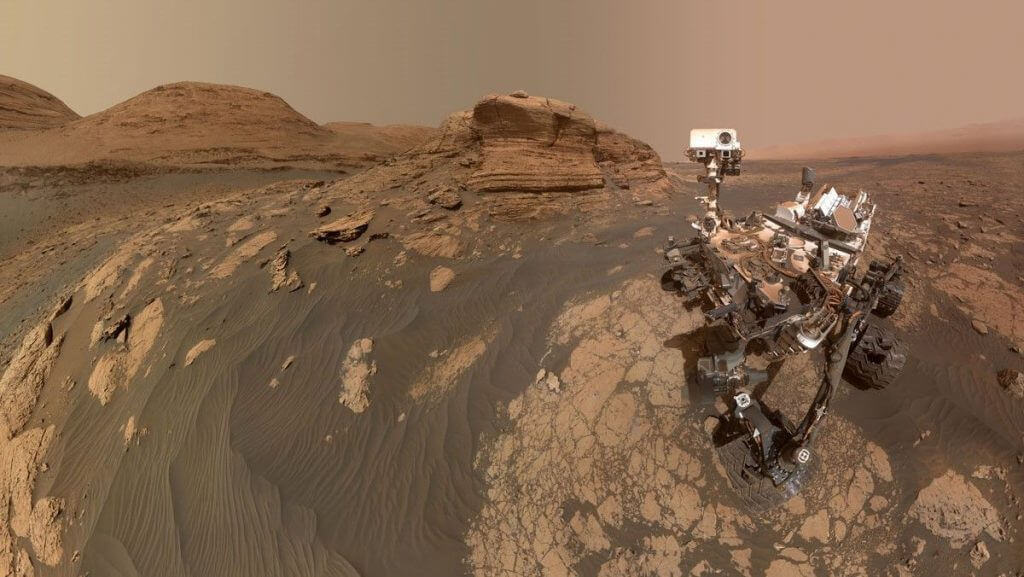

The Curiosity rover has been exploring Mars for 10 years. Here’s what we’ve learned. (Image Credit: Space.com)

NASA’s Curiosity rover has hit a major milestone: the robot is celebrating the 10th anniversary of its landing on Mars on Aug. 5, 2012.

Over the decade, the rover has greatly advanced our understanding of the Red Planet through its exploration and research. Curiosity‘s primary mission objective was to determine whether or not Mars was habitable in the past. Through previous missions, scientists had already determined that water was once present on Mars and, in fact, is currently present on Mars in the form of ice. But water alone isn’t enough to support life.

“Determining habitability requires knowing if there were things like organic molecules — carbon-containing molecules that life needs — sources of energy, other molecules that life needs, like nitrogen, phosphorus, oxygen,” Curiosity deputy project scientist Abigail Fraeman, who is also a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told Space.com. “And we have found that all of those were there.”

Related: Celebrate 10 years of NASA’s Curiosity rover with these incredible images (gallery)

In order to find these key signatures of habitability on Mars, Curiosity carries with it tools to drill into the surface of the planet and spectrometers like the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) and Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) that can analyze the resulting samples. Within the rover’s first few years on the planet, it had already discovered key requirements for life.

“So we found, one, Mars was habitable, and two, that those habitable environments persisted for tens of millions of years, most likely, maybe even hundreds of millions of years, which was surprising and exciting,” Fraeman said.

The rover’s research into the rock and soil of Mars also yielded new information about groundwater cycles on Mars. “All of the rocks that we’ve driven through show not only the signature of water when they were originally deposited, but this later overprinting of one or two or dozens of cycles of groundwater circulating through the rocks,” Fraeman said. “And so it really emphasized the importance of subsurface water on Mars, which is something that would have been a really important process.”

But in a decade of exploration, Curiosity has discovered much more than the building blocks of life. “One of the types of science that doesn’t get mentioned a whole lot, but is really important and really interesting, is the environmental science we’ve been doing,” Fraeman said.

Curiosity has radiation detectors and environmental and atmospheric sensors that have been put to good use on Mars. For instance, throughout its wanderings, when Curiosity approached geological formations like cliffs and buttes, the rover’s instruments detected that the rocks blocked radiation from reaching it. “We can now use that for models for future astronauts. For example, can you use natural terrain as shielding?” Fraeman said.

She’s also enthralled by Curiosity’s study of Martian weather, noting that just last year, Curiosity photographed beautiful clouds known as noctilucent clouds, which appear at sunset during winter.

Although Curiosity’s original mission timeline lasted just under two Earth years, a decade out the rover continues to be in relatively good health — good enough to continue its work. “We do have a little bit of arthritis, a little bit of aches and pains in the joints,” Fraeman said. Its wheels, for instance, have developed quite a few holes after some 17.5 miles (28 kilometers) of travel with a 2,000-foot (600 meters) elevation gain. But Fraeman noted that the wheels are accumulating damage at a relatively slow rate, allowing Curiosity to continue moving.

“I think what’s most remarkable to me is all the science instruments are basically working as well as they did when we landed,” she said. “We’re still able to do the same quality and breadth of science that we were 10 years ago, and that’s pretty extraordinary.”

Next up for Curiosity is an investigation into what happened to the once-habitable climate of Mars and how long the region remained habitable as the water began to dry up. While the rover spent the past decade exploring lake environments — most recently, a region where sand dunes formed as lakes disappeared — the team is now sending the explorer even higher up Mount Sharp.

“We’re so close to reaching what we call the Layered-Sulfate unit, which is a completely different portion of Mount Sharp,” Fraeman said. “We see from orbit that it has a different texture, a different mineralogy, and we think this is going to represent a very different environmental time on Mars. We’re excited to see just what this environmental change was, how it’s reflected in the rock record, and what that means for habitability.”

But before Curiosity gets to all that, the team is going to spend a little time celebrating the anniversary. “Those of us who are local in Pasadena, we’re going to have a party. We’re going to get some Thai food, we’ll have a raffle,” Fraeman said. “I think it’ll just be a joyous occasion to celebrate the accomplishments and hopefully look forward to more fun science.”

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.