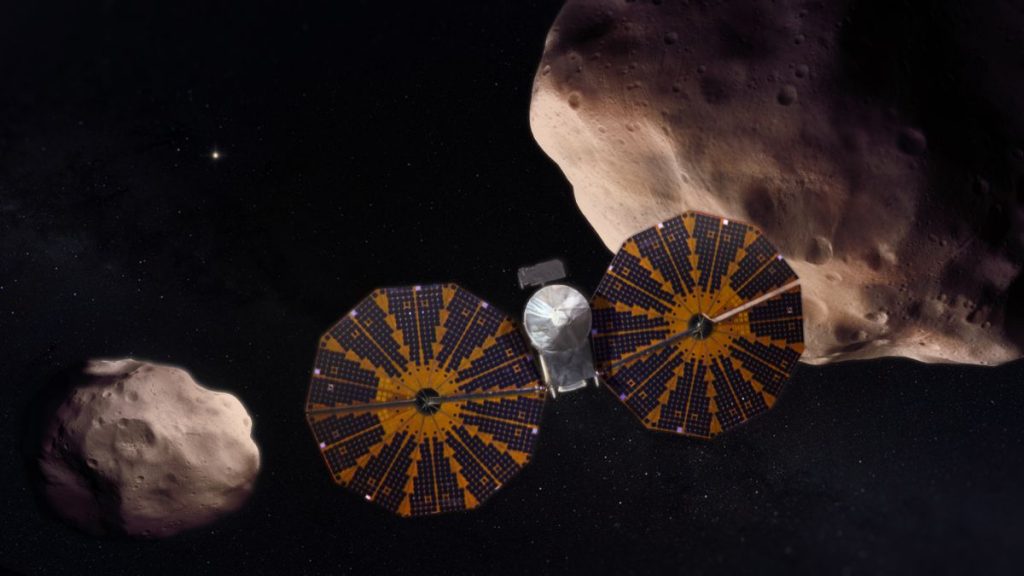

The asteroid targets of this NASA mission are turning out to be very strange (Image Credit: Space.com)

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft still has five years of trekking through space before it sees its first Trojan asteroid, but mission scientists are already getting a sense of what these rocks look like.

The Lucy mission launched in October 2021 to survey Trojan asteroids, which orbit the sun at the same distance as Jupiter, with one cluster ahead of the giant planet and a second cluster behind it. The mission will give scientists their first close look at this class of asteroid, which are “fossils” left over from the formation of the solar system. But mission scientists still have plenty of work to do as Lucy cruises through space.

“We have been very busy getting ready for the Lucy mission,” Marc Buie, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, said during a news conference held on Tuesday (Oct. 4) in conjunction with the annual conference of the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society.

Related: Meet the 8 asteroids NASA’s Lucy spacecraft will visit

“I’m trying to figure out as much as we can about the Lucy targets,” Buie said. Specifically, he’s looking to intel for flyby planning and navigation purposes. “Think of what I’m talking about here today as a report from the reconnaissance team.”

The reconnaissance campaign relies on occultations, which occur when a celestial body passes in front of a star as seen from Earth. By clocking when the star disappears and reappears from a cluster of locations on the ground, astronomers can sketch a basic outline, connect-the-dots-style, of the object doing the blocking. The more occultation observations scientists can make, the more detailed that outline becomes.

The Lucy occultation team, which Buie leads, began observations of the mission’s five primary targets in 2018, but the opportunities have been particularly numerous this year.

“2022 is the craziest year ever for me for doing occultations,” Buie said, citing 13 international excursions in a single three-month period. Because occultations are visible from a specific patch of Earth, observers have deployed to locations around the globe; Buie spent a chunk of the summer chasing occultations across Australia.

“This year is anything but normal,” Buie said. “I had to turn events away; I probably could have chased a hundred different events all over the world.”

The bonanza comes courtesy of the galaxy itself. As seen from Earth, the Trojans pass in front of the Milky Way twice each 12-year trip around the sun, and during this passage there are many stars available to block out. From now until Trojan flybys begin in 2027, Buie expects fewer occultation observing campaigns, perhaps only two or three for each primary target.

But each successive occultation is a valuable opportunity, giving scientists new points to add to their outline of the space rock in question. And so far, those outlines are turning out to be impressively irregular, Buie said.

“Every one of the targets has topography,” he said. “Could be craters, could be other geological structures — we’re gonna see a lot when we get there.”

All told, Lucy is currently expected to observe nine different asteroids, the first of which is in the main belt. The Trojan flybys will begin in August 2027 and the itinerary was designed around five particular asteroids: Eurybates, Polymele, Leucus, Orus and Patroclus. Three of those have moons; Patroclus’ is nearly the same size as the main body, while Eurybates’ and Polymele’s are much smaller.

Two Lucy targets in particular stand out to Buie: Polymele, which the spacecraft will fly past in September 2027, and Leucus, slated for an April 2028 flyby.

Occultation work has already offered scientists two surprises about Polymele. Astronomers detected a small, as-yet-unnamed moon orbiting Polymele during occultation observations gathered in March. And the outline revealed so far suggests that the main rock is strange all on its own. “It’s actually a kind of hamburger shape, a very oblate object,” Buie said.

Meanwhile, Leucus seems to be missing a chunk of its southern side. “That one could be duking it out with Polymele for the award for the strangest object we’re gonna see,” Buie said. “Leucus is just a bizarre shape and I can’t wait to get there and take a look at this one up close.”

The occultation work isn’t just about getting a sneak peek while waiting for the flybys proper. Buie also said he hopes that by comparing the occultation results with Lucy’s observations, scientists can understand and vet the technique enough to apply it in detail and with confidence to asteroids that no spacecraft will ever visit.

“I think we can start characterizing the cratering record on an object without sending a spacecraft there,” he said. “Then I can go off and survey thousands of asteroids. Whatever your favorite asteroid is — whether it’s near-earth asteroid or all the way out to the Kuiper Belt, independent of the distance — I can tell you, ‘This object has never been hit’ or ‘This object has been beat up like crazy.'”

During a second presentation on Wednesday (Oct. 5), Buie even suggested that astronomers could build a robotic occultation observatory by spreading out a network of telescopes equipped for the technique. The observatory will miss some asteroids for which scientists do not yet have an accurate location, but with robotic capabilities could attempt thousands of observations each year to compensate.

The presentation comes as the Lucy spacecraft is facing a milestone, with a flyby of Earth scheduled for Oct. 16. The maneuver will be the first of two gravity assists the spacecraft makes at Earth to gather speed and set its course out through the asteroid belt to Jupiter’s orbit; the second will come in late 2024.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.