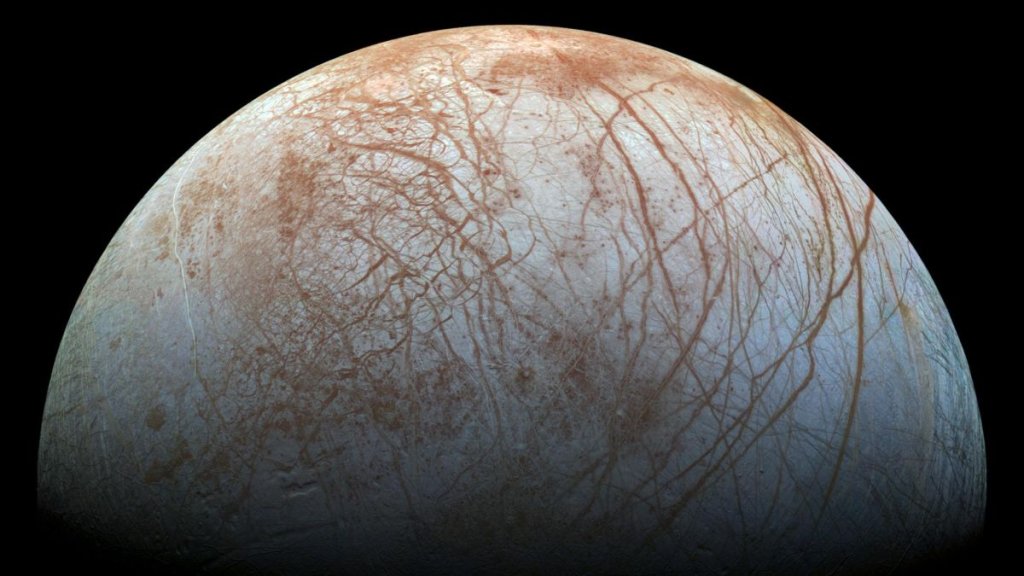

Surprise! Jupiter’s ocean moon Europa may not have a fully formed core (Image Credit: Space.com)

The core of Jupiter’s ocean moon Europa might have formed billions of years after the rest of it did, if indeed it has formed at all, a new study finds.

Europa, Jupiter’s fourth-largest moon, is covered in an icy shell. However, researchers suspect that underneath its frozen crust, Europa hosts a saltwater ocean churning over its rocky mantle. It may possess “more liquid water than Earth,” study lead author Kevin Trinh, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe, told Space.com.

Previous research suggests that Europa may be habitable — for instance, seafloor volcanoes and hydrothermal vents may help deliver life-sustaining heat and biologically useful molecules into its ocean. In order to know whether such potentially life-supporting activity might take place on Europa, scientists must understand the nature of the Jupiter moon’s interior and how it might have evolved over time.

“While Europa is famously known as a potentially habitable ocean world, over 90% of Europa’s mass comes from rock and metal,” Trinh said.

Related: Alien-life hunters are eyeing icy ocean moons Europa and Enceladus

After NASA’s Galileo spacecraft reached the Jovian system in 1995, its analysis of Europa’s gravity field suggested that Europa’s interior, like that of Earth, is divided into a metallic core and a rocky mantle. Subsequent research often assumed that Europa’s interior split into these layers as, or soon after, the Jovian moon formed.

Now, “to our surprise, we found that Europa may have spent most of its life without a fully formed metallic core — that is, if such a core exists at all,” Trinh said.

A 2021 study that reexamined the Galileo data suggested that Europa might be less massive near its center than previously thought. This would then raise the question of whether it possesses a fully formed core.

One reason Europa might not have a fully formed core is that it likely formed at much colder temperatures than Earth did, due to the icy moon’s greater distance from the sun. This means that, as Europa’s building blocks came together, they may not have melted and separated into a metallic core and rocky mantle.

Trinh and his colleagues developed computer models of how temperatures in Europa’s interior changed over 4.5 billion years, assuming relatively low initial temperatures of minus 99 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 73 degrees Celsius) to 80 degrees F (26 degrees C).

The scientists found that, in about the first 500,000 years after Europa’s birth, its ocean and ice shell may have formed as chemical reactions led water to gradually ascend from its mantle. Europa’s metallic core, if it exists, would likely have started forming at least a billion years after the moon was born; heat from radioactive elements and tidal churning from Jupiter’s gravitational pull may have melted the core slowly over Europa’s lifetime.

Europa may still be gradually separating into multiple layers today, the researchers noted. The formation of a metallic core would help make Europa more habitable, “since metallic core formation could deliver a heat pulse to the rocky mantle,” Trinh said.

NASA’s planned Europa Clipper mission may help scan the Jovian moon’s gravity to “improve our understanding of how mass is distributed inside Europa, which relates to the existence of Europa’s metallic core,” Trinh noted.

The new study was published online today (June 16) in the journal Science Advances.