Should we regulate the moon? Scientists call for international plan to share lunar water and resources (Image Credit: Space.com)

There continues to be guesswork regarding resources available on the moon.

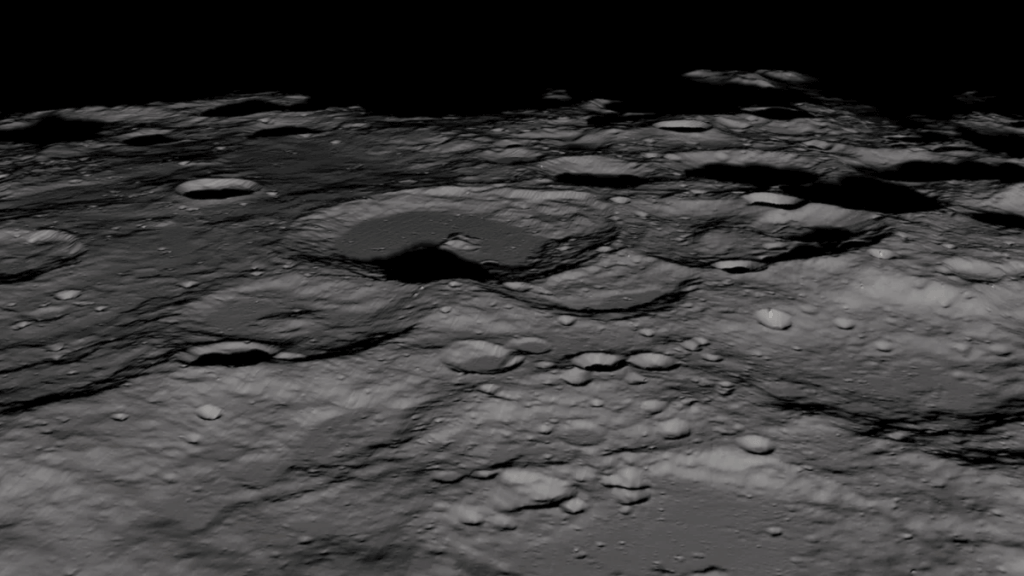

Clearly, a leading hot topic is whether or not super-chilly water ice at the lunar south pole is truly ripe for the picking and processing into oxygen, hydrogen and other essentials needed for life support, even rocket fuel.

Indeed, exploitable water ice is on NASA’s Artemis agenda, a prospect viewed as enabling a “sustainable” human presence on that bleak and cratered world. Lunar water ice is thought to reside within “cold traps,” permanently-shadowed regions, or PSRs. That elixir for life, along with a bountiful wellspring of other moon resources, could help shore up a self-sustaining space economy. But keep that thought. There’s a need for first things first.

Campaign trail

What’s urgently needed is a moon prospecting effort to show the “reserve” potential of the lunar south pole.

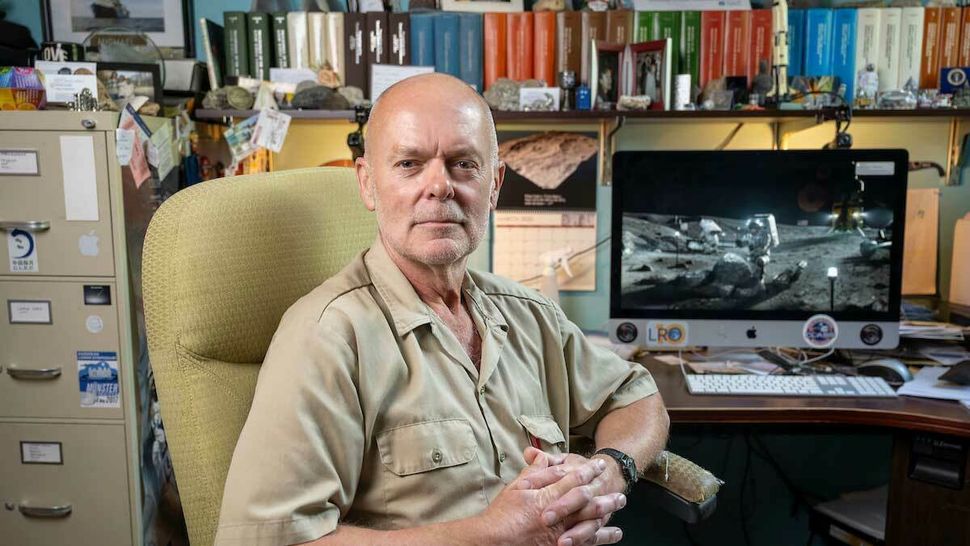

It’s a lively election year in the United States. Also on the campaign trail, so to speak, is Clive Neal, an expert in lunar exploration and professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences at the University of Notre Dame.

Last month, the celestial crusade has Neal detailing an initial International Lunar Resources Prospecting Campaign at the 2024 International Geological Congress, that was held Aug. 25-31 in Busan, South Korea.

“We need to formalize this campaign in terms of getting people onboard, to take it seriously. It’s time for collaboration and cooperation,” Neal tells Space.com. To achieve this, a dedicated coordinated campaign of lunar missions is required. The moon’s resource potential must be quantitatively evaluated, he argues.

Like water ice, there are other resources that will be useful, Neal advises, and good science, exploration and commercial interactions await. The International Lunar Resources Prospecting Campaign (ILRPC) is achieved by coordination, he said.

Resource and reserve

Neal flags the fact that the term “resource” in a lunar context has been used interchangeably with “reserve.” Doing so has caused confusion.

Based upon current knowledge and likely users, the only potential lunar reserve is oxygen from regolith as it is present in about the same proportion anywhere on the moon. Defining it as a reserve, however, requires economic and legal issues yet to be fully addressed.

Neal said that a reserve — as framed by the U.S. Geological Survey — defines the term “as that portion of an identified resource from which a usable mineral or energy commodity can be economically and legally extracted at the time of determination.”

Between now and the end of the decade, 30 robotic lunar missions are funded and under development; 16 more have been proposed, but not yet funded, Neal notes. “The whole point of the campaign is that we don’t have to create new missions, they are either there, have gone, or are going.”

Lunar missions are now and will be churning out varying data sets. An entity is needed to coordinate between different moon missions, including those of China and Russia, said Neal. Implementing the ILRPC requires a non-governmental organization, best representing a community-driven undertaking, he contends.

International interest

Ongoing and scheduled missions demonstrate the international interest in the south pole region of the moon.

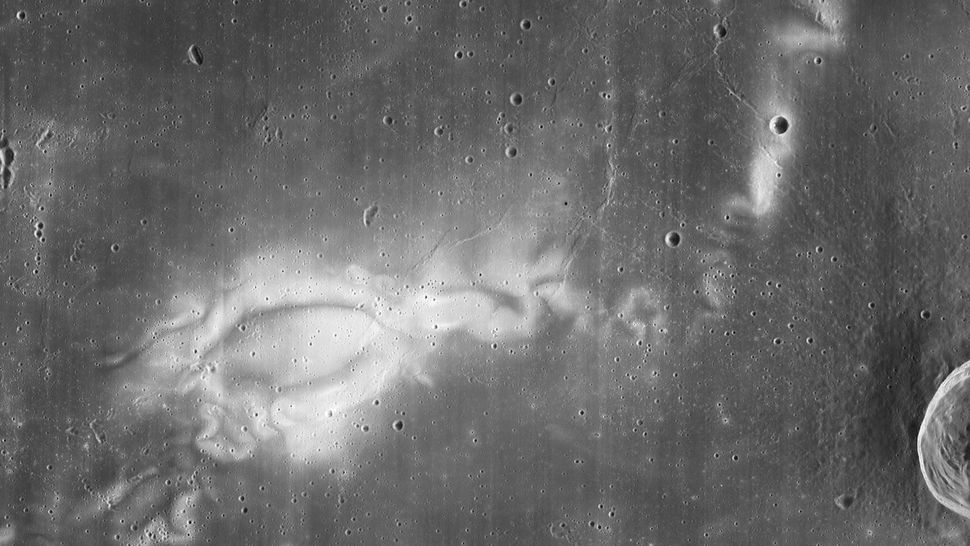

For instance, the veteran NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is now dutifully carrying out extended science objectives, including a focus on volatiles at the polar regions.

Then there’s the Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter now in operation around the moon. So, too, is the orbital component of India’s Chandrayaan-2 mission from 2019.

There is an opportunity to integrate these different mission datasets and future spacecraft outputs to derive useful products for the good of all lunar polar volatiles, Neal said.

On the books

Upcoming and targeted for the moon includes NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer, an orbiter geared to gauge the form, abundance, and distribution of water on the moon and the lunar water cycle through thermal and infrared mapping of the lunar surface.

Apparently still caught in lunar limbo is the NASA Artemis lunar rover, the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, or VIPER. The space agency canceled VIPER due to budget concerns. But it seems to be still rolling forward as commercial and/or international partners may be interested in flying the moon machine to the lunar south pole.

Also, lawmakers in Congress are taking a budgetary hard-look at the situation, prodded in part by a save the VIPER letter-writing campaign now involving 4,800-plus supporters. In the interim, VIPER recently entered thermal vacuum chamber testing to be completed by October.

Later this year is NASA’s Polar Resources Ice Mining Experiment-1, slated to fly on the private Intuitive Machines IM-2 moon lander as part of the Commercial Lunar Payloads Services endeavor.

If IM-2’s touchdown is achieved, a Micro Nova Hopper, a propulsive drone funded by NASA, is to be deployed and jump across the lunar surface, even dive into the permanently shadowed floor of Marston crater. The hopper’s goal is to yield the first direct surface measurement of hydrogen, a key indicator for the presence of water.

On the books is the LUnar Polar EXploration mission (LUPEX) mission from the Japanese Space Agency in collaboration with the Indian Space Agency to explore Shackleton — de Gerlache ridge for volatiles.

Add in the European Space Agency’s Package for Resource Observation and in-Situ Prospecting for Exploration, Commercial exploitation and Transportation (PROSPECT), built for lunar surface/subsurface probing to evaluate volatiles.

China and Russia are also working on robotic missions to investigate the south pole for volatile resources as a prelude to establishing an International Lunar Research Station.

Dealing with Datasets

“This is an iterative approach. While agencies and organizations are putting money into ISRU [in-situ resource utilization], we don’t even know if we can extract the water ice. We don’t know if this is an economically viable resource on the moon,” said Neal. “Without taking fundamental steps, investments in ISRU technology could all be vaporware.”

Neal knows that coordinating this campaign of cooperation and collaboration will not be easy.

Any lunar resource evaluation or prospecting campaign will need to be international in nature, Neal concludes, as no one space agency will have the money or mandate to conduct it alone.

“This is where science and exploration come together. Everybody wins if science and exploration go together,” Neal said.