Satellite servicing industry faces uncertain military demand (Image Credit: Space News)

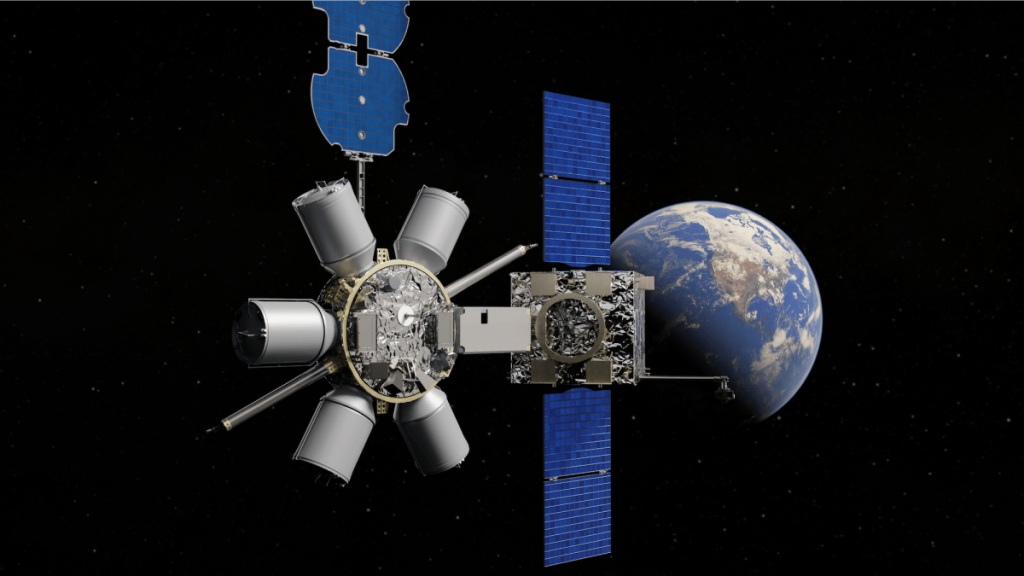

WASHINGTON — The burgeoning in-space satellite servicing industry is positioning itself to transform orbital operations, from refueling to potential in-space repairs. Companies are eager to demonstrate their capabilities to a crucial customer: the U.S. military. But convincing the Pentagon to trust commercial providers with delicate, high-value national security satellites remains a significant challenge.

The ability to refuel satellites in orbit is particularly appealing to the U.S. military, which operates some of the most expensive spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit. Keeping these critical assets functional for as long as possible is a top priority. However, beyond basic refueling, the military remains uncertain about adopting other ISAM (in-space servicing, assembly and manufacturing) services.

Companies in the ISAM sector view the military as a critical early customer needed to spur the market and attract venture capital. For now, refueling remains the most compelling immediate service, said Richard Palmer, deputy director of capability and resource integration at U.S. Space Command. Palmer pointed out that more advanced services like component replacement or payload repairs have not yet won military buy-in, largely due to budget constraints and technical uncertainties.

“Refueling satellites in orbit is easy to conceptualize,” Palmer said last week at the MilSat Symposium in Mountain View, California. But for other in-orbit services, there’s no clear vision yet on how they would realistically be used.

The Department of Defense (DoD) spends billions annually on satellite programs supporting navigation, communication, and intelligence missions. While ISAM companies are hopeful that the military might embrace more sophisticated in-orbit repairs, Palmer tempered expectations, saying budget priorities like the military’s “protect and defend architecture” and modernization of legacy systems are paramount.

The conversation around satellite servicing at Space Command is still heavily skewed toward refueling. Palmer noted potential use cases beyond that, such as replacing solar panels, batteries or other critical components, but added that trust is a significant hurdle. Military satellites, worth billions, require a high level of confidence in any commercial partner attempting close-range operations.

“There’s a lot of trust that has to go into allowing someone to approach and work on these satellites,” Palmer said. Beyond trust, he underscored that funding is a looming constraint. “We have too many requirements today for the resources we have,” he explained. Until there’s a change in budget allocation, those other services won’t get the funding they might need.

A divide over military needs

Andrew Williams, deputy space technology executive at the Air Force Research Laboratory, pointed to a disconnect between ISAM’s commercial vision and military priorities. In-orbit servicing demonstrations are innovative, but they’re focused on things that don’t necessarily meet military demands, Williams said at the MilSat Symposium, adding that elaborate in-orbit repair missions are questionable given their cost and complexity.

Opinions vary even within military circles. Williams advocated for simpler logistical solutions like resupply and maneuver capabilities that align with military mission needs. Instead of high-cost, complex repair operations, he argued that the military is looking for more adaptable solutions to enable maneuverable satellites.

Lori Gordon, director of the Space Enterprise Evolution Directorate at Aerospace Corp., described the ISAM industry as being in a “deer in the headlights” moment. “The big question is how does commercial integrate with government architectures?” she said.

Military, allied and private-sector coordination is crucial, said Gordon. Aerospace Corp., a federally funded research organization, is helping bridge this gap by working with U.S. allies and the private sector to match testing facilities with developers of ISAM technologies, she added.

A Path forward for ISAM

Today, over 400 distinct ISAM capabilities have been developed, but only a handful have reached operational deployment, according to Gordon. The industry needs clearer pathways to government contracts and increased investor confidence to move beyond the so-called “valley of death” — a stage in which technologies fail to transition from prototype to viable product.

“Providing more information to investors, regulators, and insurers is essential,” Gordon noted. Although the DoD is increasingly integrating commercial satellite communications, it expects ISAM firms to lead in satellite servicing. For ISAM, it’s a waiting game, hoping for early government commitments to kickstart private investment.

Gordon stressed that this is a critical time for the industry to work with the government to better understand how they can collaborate in support of the military space infrastructure.