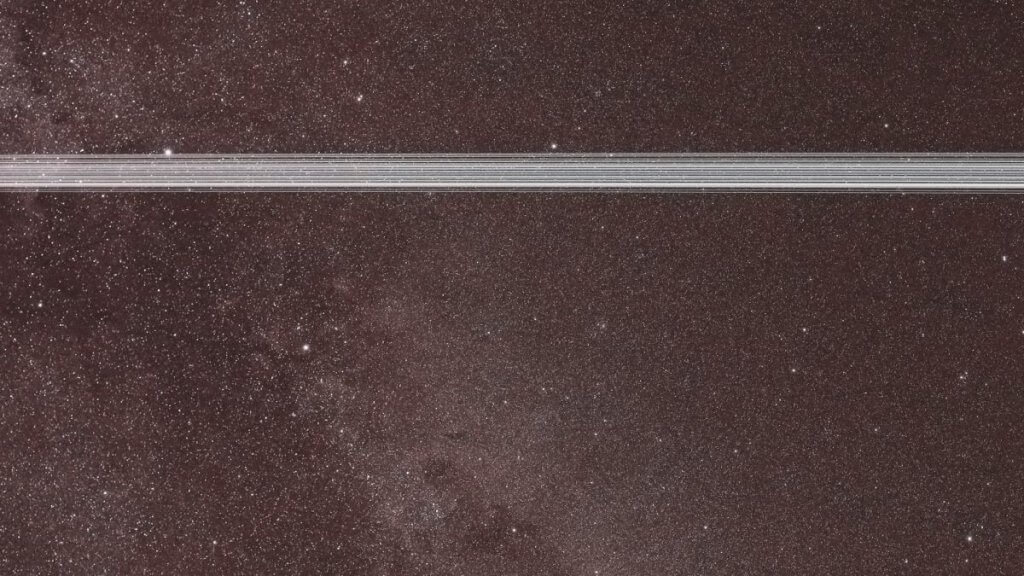

Satellite megaconstellations are threatening astronomy. What can be done? (Image Credit: Space.com)

Star light, star bright, first star I see tonight; I wish I may, I wish I might have the wish I wish tonight.

That well-known nursery rhyme has a number of astronomers wishing away the dawn of all those Earth-orbiting megaconstellations that are dotting the sky today and into the future.

With the advancing Starlink and OneWeb satellite constellations, as well as Amazon’s projected Project Kuiper internet network — and even more large satellite initiatives underway — astronomers are becoming increasingly concerned of being blinded by the light from an estimated 400,000 satellites planned for low Earth orbit in the coming years.

A common reply from megaconstellation backers is: What’s the worry? After all, any instrument needed to truly scrutinize the cosmos should be off-Earth in the first place. Isn’t that why the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, among a gaggle of space-based scopes, were launched?

Related: Astronomers urged to fight ‘tooth and nail’ to protect dark skies

Common understanding

The question of how we should protect dark skies in the future was recently broached by Andrew Williams, an external relations officer at the European Southern Observatory (ESO). He is also co-lead of the International Astronomical Union’s Center for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference.

“The presence of potentially hundreds of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit is creating an urgent space governance challenge, impacting both the professional conduct of astronomy and the pristine view of the night sky,” Williams said February 9 at a “Dark & Quiet Skies: The Way Ahead” event hosted by the European Space Policy Institute.

That view has been shared by Simonetta Di Pippo, recent director of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs at a Dark and Quiet Skies initiative back in late 2020.

“We need to find a common understanding. On the one hand side, constellations can help provide global internet coverage and bring the remaining 3 billion people online — a giant leap forward in connecting the globe,” Di Pippo said.

“But at the same time, we must protect the science of astronomy. We must engineer a step-change in discussions at the international level among all relevant actors. And the [UN’s] Dark and Quiet Skies initiative should to exactly that … proposing recommendations which can eventually be acted upon either by local governments or agreed to at the international level,” said Di Pippo.

Operational licensing

Lofting precision astronomical machinery into space, leaving ground-situated observations behind, isn’t a solution, said Richard Green, assistant director for government relations at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory in Tucson, Arizona.

“The point is that we can’t come anywhere near duplicating major ground-based capabilities in space,” Green said. “And this doesn’t count the hundreds of meter-class facilities, which are used for everything from amateur astronomy to planetary defense.”

The most rapid progress in mitigating the impacts of megaconstellations on astronomy come from cooperative efforts by industry, Green said, some of which are now made a condition of operational licensing by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

Positive outcome

“SpaceX has really been an industry leader in working to find an optical coating that should reduce the brightness apparent on the ground by roughly 50 times. They also voluntarily executed a Coordination Agreement with the National Science Foundation,” Green said.

In that agreement, SpaceX promised to make continuing best efforts to reduce optical visibility further, not to downlink directly onto ground-based radio telescopes and to take other steps to lower their impact on astronomy.

The FCC made executing and reporting on such a coordination agreement a condition of their granting the (partial) license for the second-generation Starlink V2 satellites, Green points out, and placed a similar condition on their recent license granted to Amazon’s Kuiper, a planned constellation of 3,236 satellites in low-Earth orbit to deliver low-latency broadband internet.

“The astronomy community had met with the FCC earlier, and urged them to consider such an approach, so that is a very positive outcome,” Green said.

As a forecast of things to come, Green says that the trend working against astronomy with the constellations is the strong push for direct-to-cell communications.

“That requires a large-area antenna for each satellite to capture the faint signals from cell phones, so even with treatment of the surface, the push toward larger and larger space-based structures will definitely increase their visibility, and therefore their impact on ground-based observations,” Green observed.

Hubble’s data archive

The thought that all astronomy should be done off-Earth also elicits a response from John Barentine, executive officer and principal consultant at Dark Sky Consulting in Tucson, Arizona. This consulting group is focused on light pollution, dark skies and astronomy.

As for space-based observatories, not all of them fly above the satellites in question, Barentine said, in particular, the Hubble Space Telescope that orbits sufficiently low that its images are sometimes directly affected by satellite trails.

Barentine points to a recent search of Hubble’s data archive by using machine learning. The result was finding more than 2,400 satellite trails in images. “We expect to see a big increase in that number for however many years of useful life the Hubble Space Telescope has left,” he said.

Of course, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) flies so far from Earth that it isn’t affected by satellites, Barentine added. “That said, there’s only one JWST and thousands of astronomers who want to use it.”

Tragedy of the commons

Ground-based observatories have been and will continue to be absolutely crucial to advancing our knowledge of the cosmos, said Barentine.

“Space, as the old adage goes, is hard; it’s also still very expensive. For the same number of dollars we can put far more effective eyes on the sky by conducting observations from the ground,” Barentine suggested. “And these facilities work in concert with missions like JWST to provide crucial follow-up observations of objects that it discovers.”

A point that Barentine also raised is that the night sky is not merely the province of astronomers.

“Everyone from casual stargazers to Indigenous peoples, who often view it as an object of religious and cultural significance, have a stake in how space is used given its impacts on the night sky,” Barentine concluded. “It doesn’t ‘belong’ to anyone, and as a commons it is subject to the famous ‘tragedy of the commons’ in which individual users deplete a resource to the detriment of all other users. So to concern ourselves only with astronomical users of the night sky is very short-sighted.”

Navigating nuisance?

Swedish scientist and writer Johan Eklöf is the author of the new book “The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms that Sustain Life” (Simon & Schuster, 2023). The work shines a light on the domino effect of diminishing darkness on our planet.

“Already today, satellites stand out, looking like bright new stars in the sky,” Eklöf told Space.com. “Thousands of them will mess up constellations. It is hard to tell if the light is bright enough to cause light pollution on the ground, but it must be investigated.”

Eklöf also advised that animals navigating by stars will probably find all the sky traffic most confusing. “I’m not aware of any studies on this yet, but we must realize that we are messing with an ancient map and it will surely have effects,” he said.

World changes

“The change from a clear night sky to one spotted by megaconstellations and space debris fundamentally changes how humanity interacts with the night sky,” said Emma Louden, a Ph.D. candidate in astronomy at Yale University.

“While this evolution is daunting for astronomers who rely on ground-based telescopes, Louden feels that “this moment is also a tremendous opportunity to revisit how we approach cutting-edge observatories.”

Astronomers are not unfamiliar with evolving how our data is collected as the world changes, Louden observed.

Hubble Space Telescope images increasingly affected by Starlink satellite streaks

“Much as the Paris Observatory, founded by Louis XIV in 1667 as a way to improve France’s ability to explore the globe by sea and to increase trade, was encroached upon by the modernization of Paris’s streets in the nineteenth century, our telescopes are now coming up against a new challenge … that of megaconstellations,” Louden added.

Similar to how the Paris Observatory had to “pivot and find new ways” to do ground-breaking astronomy, Louden suggested that there is now need to evolve into the new world of megaconstellations.

“Astronomers are no strangers to innovation and creativity. This time of change in the night sky is a chance for the community to come together and innovate for the future,” said Louden.

Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).