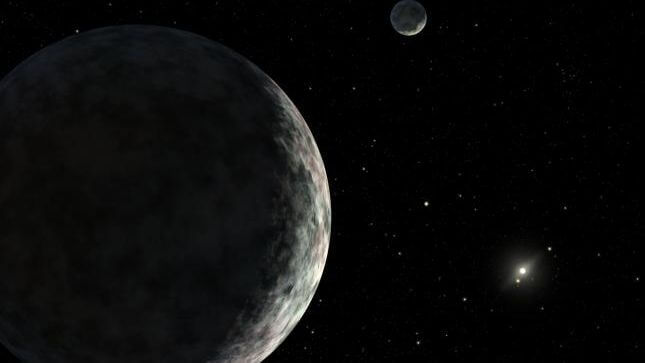

Pluto’s ‘almost twin’ dwarf planet Eris is surprisingly squishy (Image Credit: Space.com)

Close to 18 years ago, astronomers spotted a miniature, icy world named Eris billions of miles beyond Neptune. But unlike its dwarf planet cousin Pluto — which New Horizons promoted to a rich, dynamic world after its visit in 2015 — Eris has not had any robotic visitors. It is so far away from Earth, in fact, that it shows up in observations just as a single pixel of light.

All in all, scientists know very little about what happens on Eris.

Though what we do know is Eris is known to have an atmosphere that freezes and snows onto the surface below, thanks to its place near the edge of the solar system. It’s about 68 times farther from the sun than Earth is. And now, new models based on data from an array of radio telescopes in Chile have revealed more about Eris. Heat leftover from the dwarf planet’s birth seems to be oozing out and slowly flexing its icy surface.

Related: Dwarf Planet Eris is ‘Almost Perfect’ Pluto Twin

The process is causing Eris to behave less like a solid, rocky planet and “more like a soft cheese or something like that,” study co-author Francis Nimmo of the University of California Santa Cruz said in a statement. “It has a tendency to flow a bit.”

While a lot still remains unknown about Eris, it is considered an “almost perfect” twin of Pluto — both dwarf planets are nearly exactly the same size. Actually, when it was first spotted in 2005, it appeared to be slightly bigger than Pluto, triggering a debate among scientists. This had led the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to clarify its definition of a planet and demote Pluto to a dwarf planet. It was thanks to this contention in the scientific community that the IAU in 2006 named the dwarf planet Eris, after the Greek goddess of discord.

For the latest study, Nimmo and his colleague Mike Brown, a Caltech astronomer who had led the discovery of Eris in 2005 and is best known as the man who killed Pluto, estimated the mass for Eris’ very small moon Dysnomia. Eris and its satellite are mutually tidally locked, which means both face the same way toward each other. Scientists think this is because the tiny moon “raises” tides on Eris, causing the dwarf planet to spin down over 4.5 billion years.

The new findings show Eris likely has a rocky core enveloped by a convecting icy shell.

“The rock contains radioactive elements, and those produce heat. And then that heat has to get out somehow,” said Nimmo. “So as the heat escapes, it drives this slow churning in the ice.”

He and Brown suspect the surface of Eris should be “pretty smooth” as any surface features will likely be erased by flowing ice.

“So it would be nice to get some measurements of what shape Eris is because if it’s very irregular, that would not agree with our model.”

This research is described in a paper published Nov. 15 in the journal Science Advances.