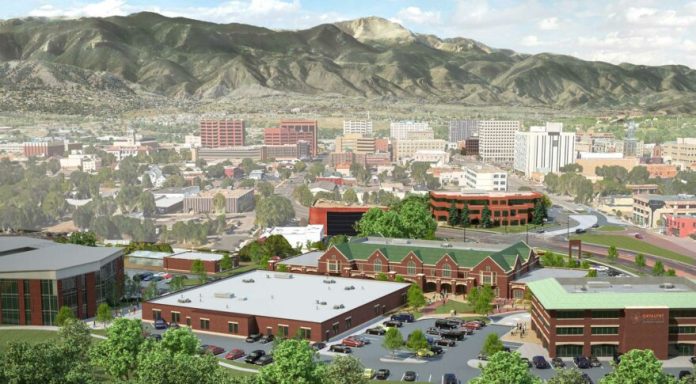

On National Security | Small businesses doing big things in DoD space programs (Image Credit: SNN)

Every six months or so, U.S. Space Command officials drop by the Catalyst Campus in Colorado Springs to check out space objects data that commercial companies collect and analyze in a software lab nicknamed “Dragon Army.”

Teams at the lab work in software sprints — building, testing and getting feedback from Space Command in short order. This work is not done under government contracts but simply to showcase companies’ space domain awareness capabilities in hopes that they will eventually land a military contract. LeoLabs, a commercial operator of surveillance radars that track objects in low Earth orbit, credits the Catalyst Campus for giving the company early exposure to Department of Defense buyers.

About 30 space startups, defense contractors and nonprofits have set up shop at the 12-acre business park. The resident companies recruit other local businesses for different projects. Campus founder and owner Kevin O’Neil said there is a long waiting list of organizations that want to move in. One reason for the growing demand is that the campus has become a magnet for DoD space buyers who want a first hand look at innovation.

The Air Force Research Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate has full-time representatives at the campus. AFRL in 2018 launched the “Catalyst Accelerator” where startups are selected to participate in three-month workshops. The latest cohort of eight companies were chosen for their capabilities in digital engineering for space applications.

SpaceNews was recently invited to tour the campus and talk to executives from several companies there.

Seth Harvey is CEO and co-founder of Bluestaq, a startup that first arrived at Catalyst in 2018 when it had just four software engineers who were trying to figure out how data could be shared across agencies that had different levels of security clearances. They were experimenting with a concept they named unified data library, or UDL, that the company envisioned as a virtual marketplace of commercial space data that could be accessed by government buyers.

“We started developing the UDL part time,” Harvey said. “Then one day Maj. Gen. Kim Crider came through. We didn’t know her. She didn’t know us.”

Crider, who recently retired, served as the Space Force’s chief technology officer and became a champion of the UDL. Having access to commercial space situational awareness data had become a burning issue for the Space Force after spending more than $1 billion on a customized platform called Joint Mission System (JMS) to track satellites and debris.

The Air Force killed JMS in 2019 and awarded Bluestaq a small business innovation research contract to develop the UDL. In March the company got a $280 million contract from the Space Force to maintain and expand the UDL over the next two years. The company now has nearly 90 employees.

Harvey said the ecosystem of startups and government mentors at the Catalyst Campus helps put companies on the map. “For a small company that is trying to break into the industry it can be a challenge to find a way to talk to the government. Here, you have the opportunity to be introduced and sit side by side with government,” he said.

O’Neil built the Catalyst Campus in 2015 on what was then blighted real estate and an abandoned railway station. He is opening other locations in the United States.

He recalled that the idea of Catalyst Campus came from a conversation O’Neil had in 2012 with then-Lt. Gen. John Hyten, who at the time was the vice commander of Air Force Space Command.

O’Neil said Hyten saw a need for a collaborative environment where the government could interact with innovators in an open forum.

“What we came up with was the Catalyst Campus,” O’Neil said.

A recurring theme heard from executives and engineers is that this type of interaction between businesses and government provides an alternative to traditional defense procurement.

AFRL’s accelerators are a case in point. When the government has a problem it needs solved quickly, rather than spend years trudging through the federal acquisition and contracting process, it gets to select the team it believes can get things done.

– Advertisement –