NGSO Fixed Satellite Service Spectrum Priority in the US: Payload Research (Image Credit: Payload)

Last month, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) updated its spectrum sharing rules for Non-Geostationary (NGSO) Fixed Satellite Service (FSS) systems to establish quantified interference protection criteria for satellite systems based on their level of spectrum priority.

NGSO FSS systems such as SpaceX’s Starlink, Eutelsat’s OneWeb, and Amazon’s Kuiper are licensed in the US through processing rounds. Systems within the same processing round are granted equal spectrum priority and are protected from harmful interference by systems in subsequent rounds.

- Under the new rules, clear interference protection levels are defined for later-round systems to protect earlier-round systems.

- The long-term interference criterion is defined as a 3% time-weighted average throughput degradation, while the short-term criterion limits the absolute increase in link unavailability to 0.4%.

Spectrum Priority 101

Internationally, satellite spectrum priority is regulated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), whereas in the US, it falls under the jurisdiction of the FCC. Satellite systems whose licenses are either filed in the US or filed abroad but whose operators seek market access in the US must comply with the FCC’s regulations.

Processing rounds: The submission of one or more new NGSO FSS space station licenses or market access applications (known as lead applications) to the FCC, triggers a processing round. In response, the FCC issues a public notice inviting interested entities to submit their “competing applications” by a specified cut-off date.

- The first processing round of the large LEO satellite constellations era, initiated by OneWeb in 2016, saw 11 additional companies participate by submitting competing applications.

- This was followed by three more rounds in 2017, 2020, and 2021, resulting in a total of 43 NGSO FSS satellite applications.

Inter-round priority: Later-round systems must protect earlier processing round systems that share the same spectrum from harmful radio frequency interference. Protection is achieved either through coordination with all operational earlier-round systems or by adhering to the FCC’s newly established protection criteria.

Priority sunset: To promote efficiency, innovation, and competition from new entrants, spectrum priority is not permanent. Protection from later applicants expires 10 years after the license’s grant date. After this period, coordination between systems occurs on an equal basis.

The processing round system is intended to create a level playing field for satellite operators, but it often pushes entities to submit applications prematurely in order to secure spectrum priority. This rush, combined with the high bond costs and deployment milestones tied to license grants, frequently prompts companies—particularly startups—to request a delay in their system’s authorization. Consequently, of the 43 applications submitted, only 18 have been granted.

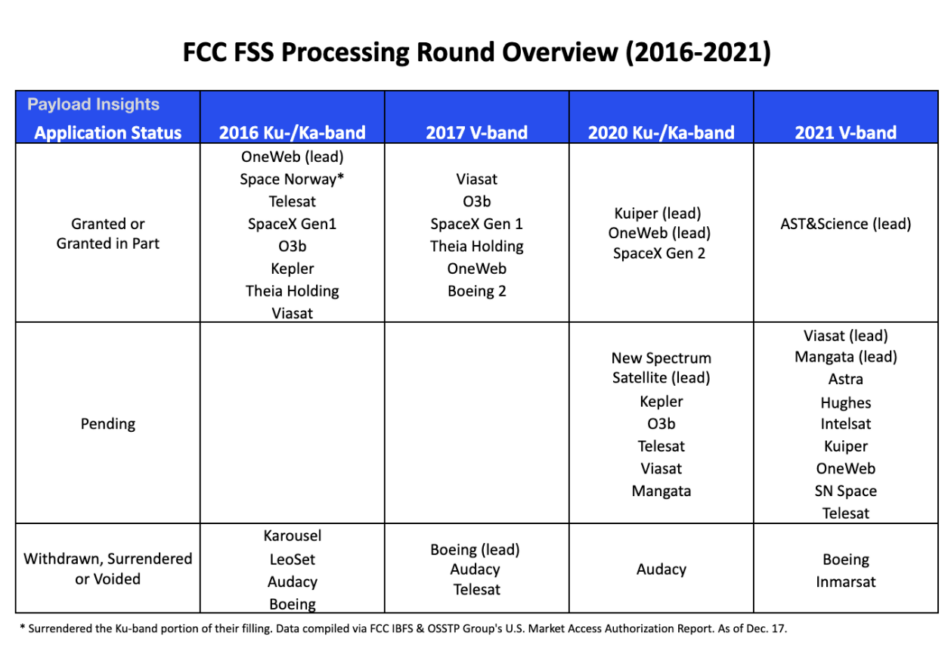

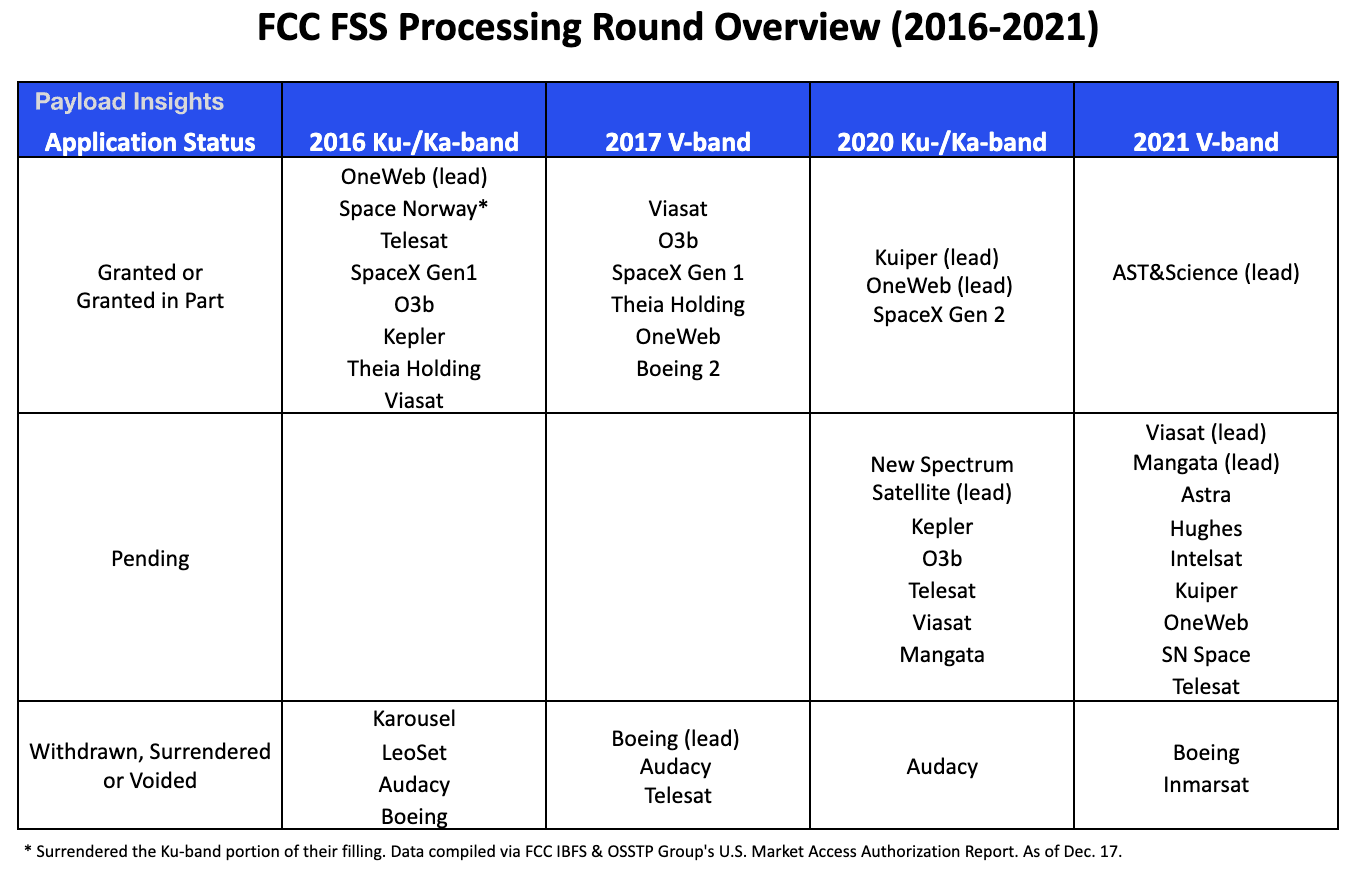

Processing Round Overview (2016-2021)

- 2016 Ku-/Ka-band processing round: Initiated by OneWeb in 2016, the round had twelve applicants, eight of which still have active licenses. The included frequencies of the round were 10.7-12.7 GHz, 14.0-14.5 GHz, 17.8-18.6 GHz, 18.8-19.3 GHz, 27.5-28.35 GHz, 28.35-29.1 GHz, and 29.5-30.0 GHz.

- 2017 V-band processing round: Initiated by Boeing—though it later withdrew its application—the round attracted nine applicants, six of which still hold active licenses. The included frequencies of the round were 37.50 – 40.00 GHz, 40.00 – 42.00 GHz, 47.20 – 50.20 GHz, and 50.40 – 51.40 GHz.

- 2020 Ku-/Ka-band processing round: Initiated by Kuiper, New Spectrum Satellite, and OneWeb, it drew ten applicants, with three licenses granted and six applications still pending. The included frequencies of the round were 10.70 – 12.70 GHz, 12.75 – 13.25 GHz, 13.85 – 14.50 GHz, 17.70 – 18.60 GHz, 18.80 – 20.20 GHz, and 27.50 – 30.00 GHz.

- 2021 V-band processing round: Initiated by Viasat, Mangata Networks, and AST&Science it attracted twelve applicants. Of these, one applicant has been granted in part, while nine applications remain pending. The included frequencies of the round were 37.5 – 40.0 GHz, 40.0 – 42.0 GHz, 47.2 – 50.2 GHz, and 50.4 – 51.4 GHz.

New Applicants: Although the FCC has not yet announced a new processing round, one is anticipated due to the accumulation of pending Ku-/Ka-band applications since the 2020 round and a new V-band application since the 2021 round. The following entities currently have pending applications that have not yet been included in any processing round:

- Kuiper (11/04/2021): Ku-band

- SN Space (11/04/2021): Ku- and Ka-band

- Intelsat (05/04/2023): Ku-band

- NSLComm (08/16/2024): Ka-band

- Logos Space (10/30/2024): Ka- and V-bands

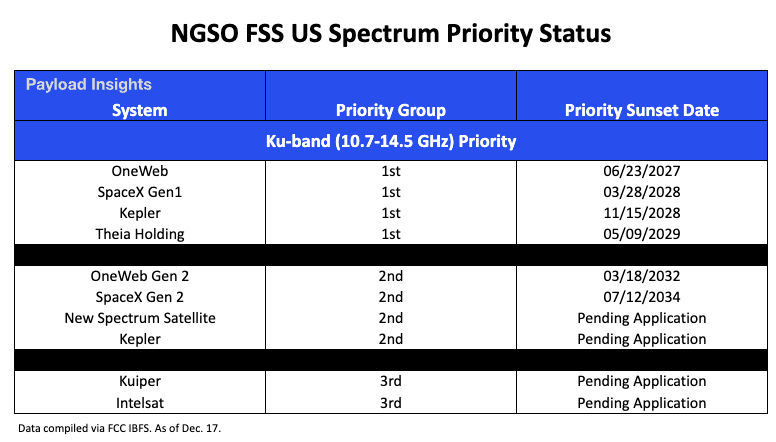

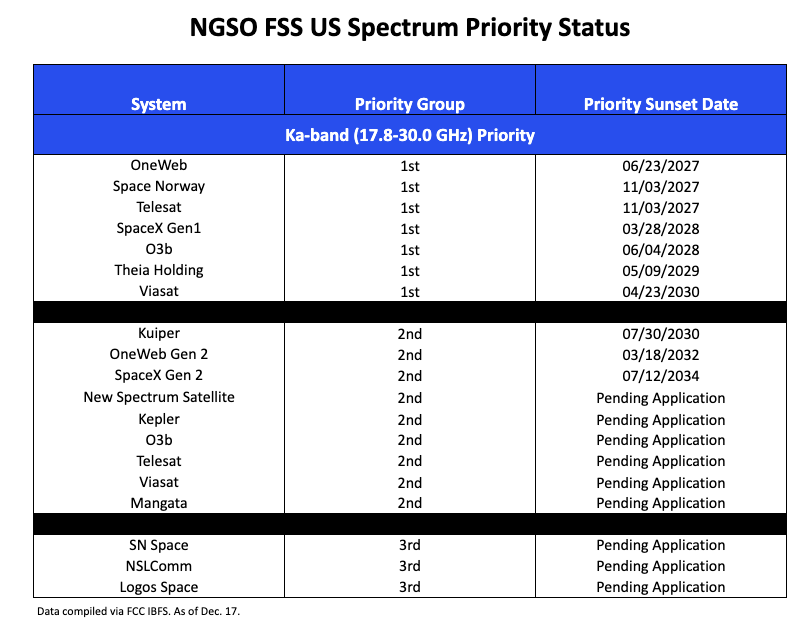

Current US Spectrum Landscape

There are 37 active NGSO FSS system applications, either granted or pending regulatory approval across the Ku-/Ka- and V-bands. These applications represent 19 separate satellite systems with various priority statuses.

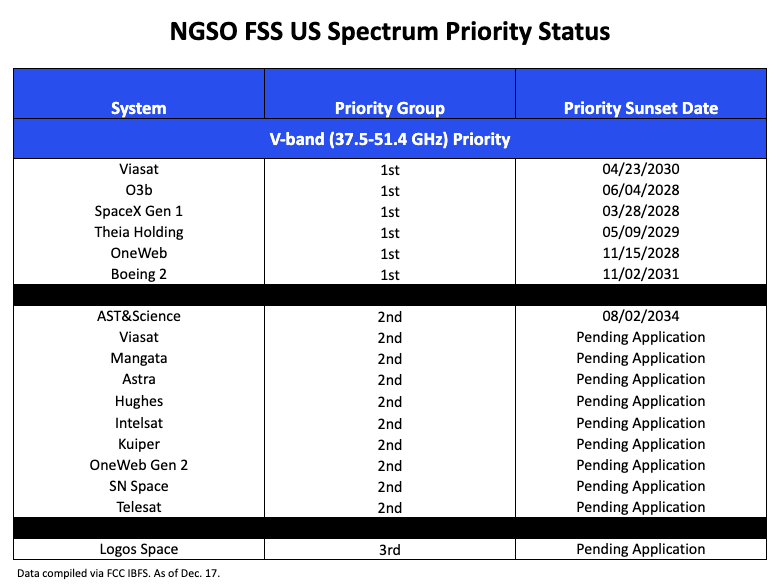

The active NGSO FSS applications, some of which are for multiple bands, are distributed as follows: 10 in Ku-band, 19 in Ka-band, and 17 in V-band. The table provides a summary of the systems in each frequency band, including their priority group that is based on the processing round and priority sunset date (if granted):

Systems in the second priority group must either establish a coordination agreement with first priority group systems or comply with the inter-round protection criteria. Similarly, new applications (third priority group) are required to protect both first and second-priority groups. Once the priority of an incumbent system sunsets, new systems will still need to coordinate with it; however, such coordination will occur on an equal basis.

Final thoughts: Interest in NGSO FSS satellite communication systems has reached an all-time high, with 37 active applications in the US alone. Only four systems are currently operational, however, leaving the sector’s future landscape uncertain. The FCC’s recent ruling establishes a clear framework for interference protection between priority groups, offering certainty to both existing and future operators.