NASA’s Voyager 1 probe swaps thrusters in tricky fix as it flies through interstellar space (Image Credit: Space.com)

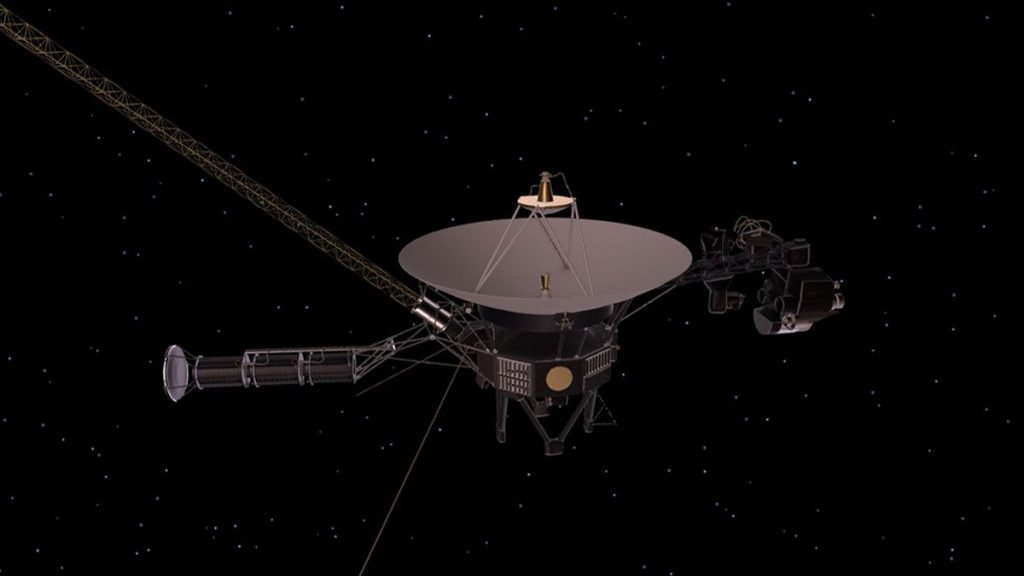

The distant and cold Voyager 1 spacecraft did a clever thruster trick to help it phone home.

Voyager 1, the most distant human object that is now flying through interstellar space, had thruster issues making it difficult for the spacecraft to stay pointed at Earth when calling home. Unless Voyager 1 could make a switch to a different thruster set, the 47-year-old spacecraft would sail on alone without help from Earth. Making matters worse, Voyager 1 is so old that sudden changes could damage the spacecraft.

“All the decisions we will have to make going forward are going to require a lot more analysis and caution than they once did,” Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory that manages the mission, said in a statement on Tuesday (Sept. 10).

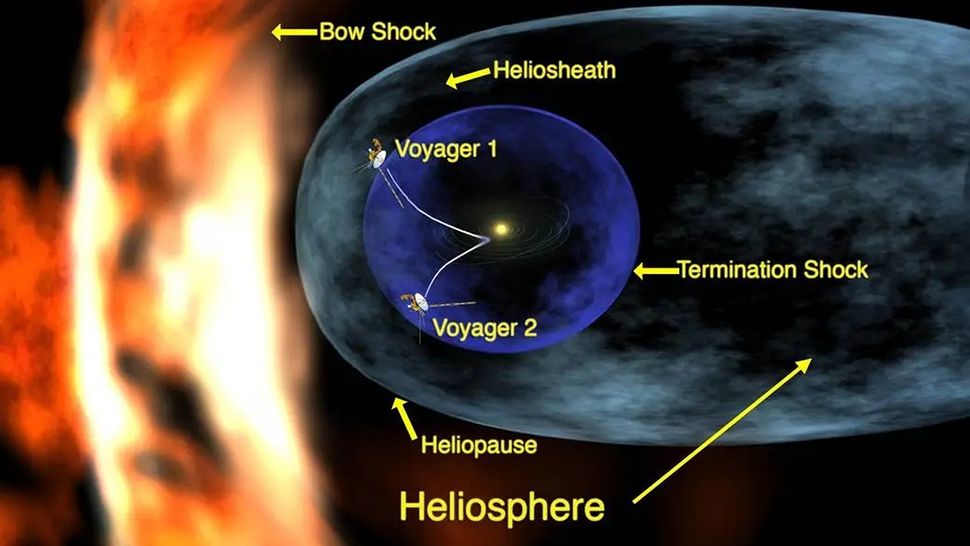

The science of Voyager 1 is critical to space science as it tells us more about interstellar space, meaning the region of the cosmos outside of the reach of the sun‘s gravity or particles.

But the spacecraft’s aging nuclear power source is much diminished, and doesn’t have much power to play with. So engineers at JPL embarked on a rescue plan to help the spacecraft’s pointing capabilities without risking its remaining functional science instruments.

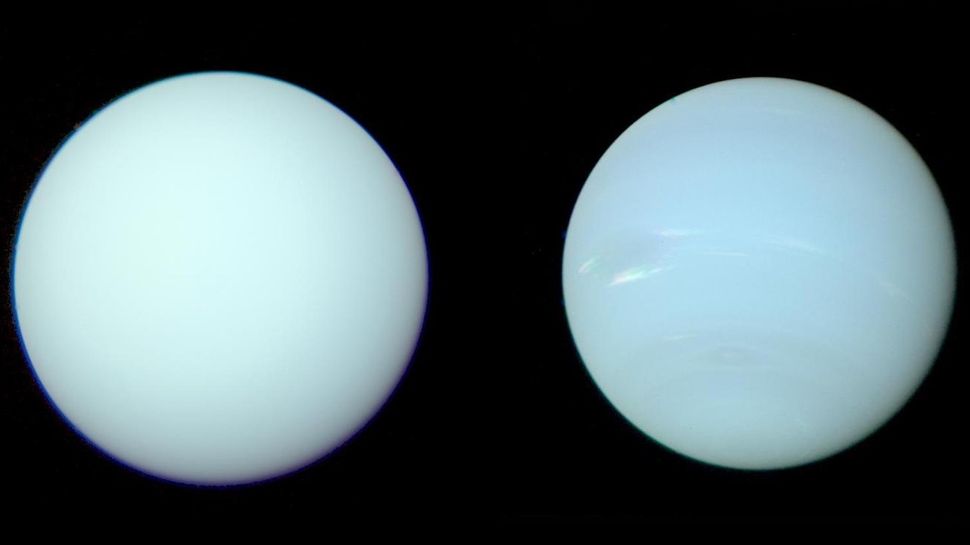

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, launched on their initial missions in 1977 to study the distant solar system. They collectively flew by four largest outer solar system planets by 1989 and continue, with tweaks for their age, to send science from afar even after both exited the solar system in the early 2010s.

As with humans, aging brought changes to the Voyager systems. The fuel tube for their thrusters have been prone to clogging for more than 20 years; that happens as a rubber diaphragm in each spacecraft fuel tank degrades, creating a silicon dioxide byproduct that clogs the line.

Luckily, each Voyager has three thruster branches available for use: two attitude branches originally designed for orientation, and one trajectory correction branch made for pathway changes in space. To be clear, engineers have been overcoming the unexpected for decades by creatively repurposing parts of Voyager. This new thruster situation, however, brought additional challenges.

On Voyager 1, a fuel tube in the first attitude propulsion branch began to clog in 2002, necessitating a switch to the second branch, NASA officials wrote in the same statement. When the second branch began acting up in 2018, Voyager 1’s orientation maneuvers all switched to the trajectory correction maneuver branch.

But with use, this single branch of the trajectory correction system has been clogging severely, to an even worse extent than either attitude propulsion branch did before.

JPL therefore decided to switch back to the attitude propulsion system, but they had to do so with less power available than in 2002. Voyager 1 is running on essential systems only, and even some of its heaters have turned off.

Between that necessary loss of some heaters — and the diminished radiant heat from fewer systems running on the spacecraft — Voyager 1’s dormant attitude propulsion thruster branch was so cold that even turning it on could cause damage.

Scrutinizing Voyager 1 carefully from afar, JPL engineers determined switching one of the heaters on for an hour would be enough. The command worked and on Aug. 27, one of the attitude thruster branches successfully reoriented Voyager 1 towards Earth for the first time in six years.

Voyager 1 required another form of creative troubleshooting recently; engineers in June resolved a data transmission problem plaguing the spacecraft for months.

Engineers at JPL plan to keep the Voyager twin spacecraft running until at least the 50th anniversary of the mission in 2027, Dodd told reporters in June at a meeting of the space science community’s outer planet assessment group, according to SpaceNews.

The group more generally deals with exploration activities in the outer reaches of the solar system; it can provide advice to NASA, but the agency does not necessarily follow recommendations, according to NASA.