NASA’s PACE satellite will study Earth’s tiniest mysteries from space: Watch it launch live Feb. 6 (Image Credit: Space.com)

On Feb. 6, NASA is scheduled to launch a major, multi-million dollar satellite to a reserved spot in Earth’s orbit. Sitting above even the International Space Station, the spacecraft called PACE (which stands for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem) has a very big goal: to monitor our planet’s health on an epic scale, starting from deep within its vast blue seas to far across its candy white clouds.

“We are studying the combined Earth system — it’s not an ocean mission, it’s not an atmosphere mission, it’s not a land mission, it’s an all-of-those-things mission,” Jeremy Werdell, the mission’s project scientist, said during a press briefing on Sunday. “What we’re doing here with PACE is really the search for the microscopic, mostly invisible, universe in the sea, and in the sky, and, in some degrees, on land.”

Those are definitely huge ideas, and we’ll soon get into the awesome details of what Werdell means with these sentiments, but if you’d like to tune into the launch of PACE, here’s what you need to know first.

Liftoff is currently scheduled to take place during the dramatic hour of 1:33 a.m. EST (0633 GMT) on Tuesday (Feb. 6). The spacecraft will launch atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. You can watch the liftoff live here at Space.com, courtesy of NASA, or directly via the space agency’s website. Coverage will begin at 12:45 a.m. EST (0545 GMT).

Related: SpaceX to launch NASA’s PACE ocean-monitoring satellite this week

What will NASA’s PACE mission do?

PACE’s mission can be divided into two overarching categories; the first has to do with Earth‘s massive, cavernous oceans.

“The oceans are 70% of our planet,” Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division, said during the briefing. “The impact the oceans have on our lives is enormous — and yet, the oceans are one of the least well-understood parts of the Earth.”

To really put this into perspective, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), we have only explored a mere 5% of the ocean. We’ve barely scratched the surface of what could be hidden in our own planet’s waters. “That means that 95 percent of our ocean is unknown,” the organization writes.

But still, the ocean’s routine carries on, guiding several major pathways in our lives. “It not only provides food that we eat and air that we breathe, but it helps regulate climate and weather,” Werdell said. Plus, he emphasizes, the ocean provides compounds used in medicines and plays a part in the economy. Fisheries, after all, provide jobs. Even beaches rely on the ocean.

And what better way to study the ocean than from the vantage point of space?

“Boats cannot be everywhere all at once in the ocean,” Werdell said. “It’s a three-dimensional fluid.”

With this in mind, one key goal of PACE — as its name certainly suggests — is to monitor the quantities and movements of underwater phytoplankton, which are microscopic organisms that stand at the crux of marine ecosystem health. Why phytoplankton specifically? Well, as Werdell says, phytoplankton sit at the base of the food chain. And, like your standard plant, they create energy through photosynthesis, taking in carbon dioxide and producing oxygen. Put those together, and this means phytoplankton control the way carbon moves through the entire ecosystem.

In the shorter term, phytoplankton dynamics therefore affect fisheries; longer term, however, Werdell says these creatures can reach into our economy, too.

This is because some phytoplankton are actually harmful, and can contaminate drinking water. Not only would contaminated water lead to a slew of health impacts for anyone drinking said water, but it could force fisheries and beaches to close down. Both are sources of jobs and other types of revenue. In fact, there are probably a bunch of other jobs that rely on healthy water, too. I can also only imagine what other uses we’d have for an extensive map of where drinking water may be contaminated — or may soon be contaminated.

“If you were to accumulate every phytoplankton and pile it up, and then compare it to all the biomass on land plants, it comprises less than 1% of all of that,” Werdell said. “Yet, it is still a community of algae, bacteria and plants in the ocean that are responsible for 50% of all the production on Earth.”

“If you’re a citizen of the world who likes breathing, and you like eating, and you like going to the beach, say thank you to a phytoplankton next time you see one,” he said.

From its 676.5-kilometer (420-mile) altitude, PACE is hopefully going to figure out where the harmful phytoplankton are, where the good ones are, where they’re all moving and how that seems to be affecting people across the globe.

It’ll do search for sunlight, or photon, interactions with the ocean (as well as the land and atmosphere, but we’ll get to that in just a second.) Once those photons get either absorbed or scattered, Werdell explains, you can sort of reverse calculate to see what thing led to those outcomes — importantly, different kind of phytoplankton look different.

“That is information that can tell you what’s actually there,” he said. “It’s as simple as that.”

Particles, storms and climate change

The other half of PACE’s mission centers on another core Earth element: Air.

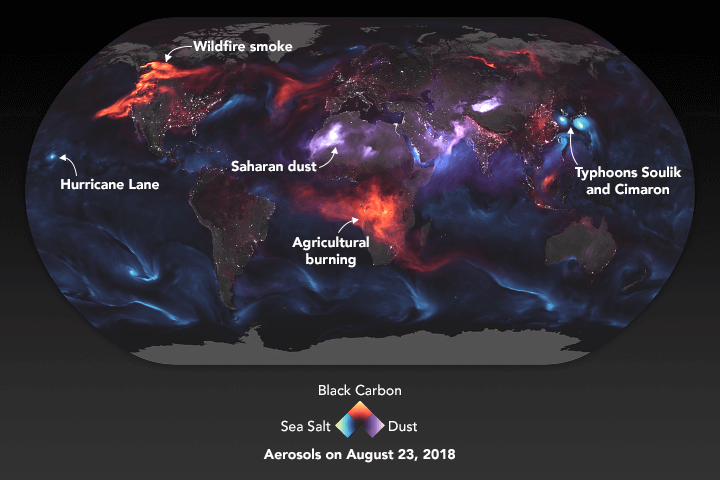

“My job is the A and C in PACE’s name,” Andy Sayer, the mission’s atmospheric scientist, said during the briefing. “That’s aerosols and clouds.”

The reason we’d want to watch over clouds might seem self-explanatory — it’d help with hurricane tracking and general storm monitoring — but what’s really interesting is why we should care about a coordinated “aerosol watch” or sorts.

Aerosols are, in short, extremely fine particles suspended in the air. We interact with them all the time; you may recall the most recent aerosol to make headlines across the United States, PM2.5.

In June of 2023, New York City ranked as having the worst air quality in the world. It was because smoke particles, specifically PM2.5 (named as such because each particle is 2.5 microns or less in diameter) blew across the nation from wildfires that occurred in Canada. As someone who lives in New York, the situation was deeply unsettling. Skyscrapers hid behind thick, yellowish smog and even air filters couldn’t quite stop the particles from gently clouding my apartment. Everyone’s eyes were glued to online, real-time air quality trackers.

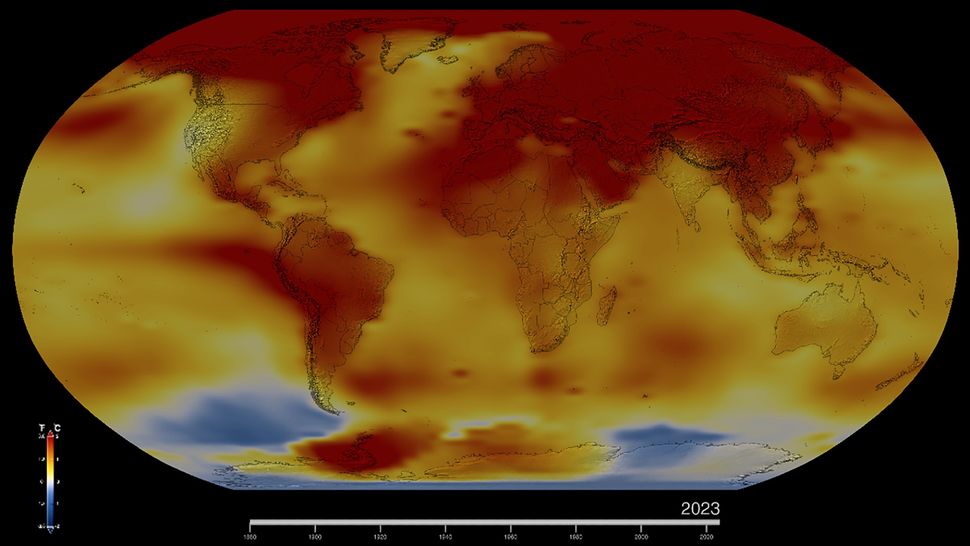

Day by day, climate change continues to ramp up — 2023 officially ranked as the hottest year documented with no downward trend in sight — we’ll likely be needing to watch air quality levels with greater scrutiny.

“The last 10 years have been the warmest since modern record keeping began,” Kate Calvin, NASA’s chief scientist and senior climate advisor, said during the briefing. “One of the great things about a mission like PACE is it’s going to give us a better understanding of the exchange of carbon between the ocean and the atmosphere.”

Human-driven climate change — aka, global warming as a result of industrial greenhouse gases and other activities — creates the right conditions for wildfires. PACE can, in this way, help scientists track air quality to determine where hotspots for bad air quality may be — or even better, where they will be based on aerosol movements.

“We can see some of them now with ground monitoring sites,” Sayer explained, “but just like Jeremy said for oceans, you can’t be in a boat everywhere all the time. You can’t have a ground monitor everywhere all the time — so space is the only way we can do this.”

But aerosols can be less menacing, too.

“If you ever take a long walk on the beach with your loved one, you take a deep breath and you get that tang in your nose, that’s an aerosol,” Sayer said. “Maybe in the winter you go to your backyard, you have a little bonfire; maybe in the summer you pull out the grill and the next day your clothes are stinky. That’s smoke; that’s yet another type of aerosol.”

And the key here is that aerosols are believed to directly impact cloud patterns and weather events — we just have to learn how. “For example, a lot of hurricanes hit the U.S. from the Atlantic. What’s at the other end of the Atlantic? The Sahara Desert,” Sayer said. “A lot of dust is coming off.”

Potentially, as those dust particles heat up the atmosphere while flying through, scientists think they help dictate the way clouds are formed, including storm clouds. Perhaps if we can understand this interaction, we’d be able to predict those events quite early.

Further, even though the ocean and air components of the PACE mission are written at the top of this spacecraft’s task list, the team expects to get some land information as well. For instance, Natasha Sadoff, NASA’s satellite needs program manager, explained that PACE will be looking out for pigments that can alert scientists to stress experienced by land vegetation.

A lot of people are interested — from the forest service, from other parts of the government, from other parts of the world — how can we use PACE data to understand where there is some sort of sickness in vegetation or in an agricultural field,” she said.

It’s rather difficult to compress the entirety of PACE’s mission down to a single article. After all, its whole point is to draw a detailed map of our planet’s smallest nooks and untouched corners like we’ve never seen before.

“PACE is covering the entire globe,” Sadoff said. “That’s very unique.”

But during the briefing, as all of these (and many more) incredible PACE-based innovations were discussed, there was one thought that seemed to penetrate almost every area of the conversation.

PACE is simply just so cool.

“It’s going to teach us about the oceans in the same way that Webb is teaching us about the cosmos,” St. Germain said in reference to the James Webb Space Telescope sitting a million miles from Earth, dutifully unveiling corners of the universe scientists likely once believed they’d never be able to see.

“Missions like this,” she said, “that you can only do from space, show us our planet in a way that we can’t see.”