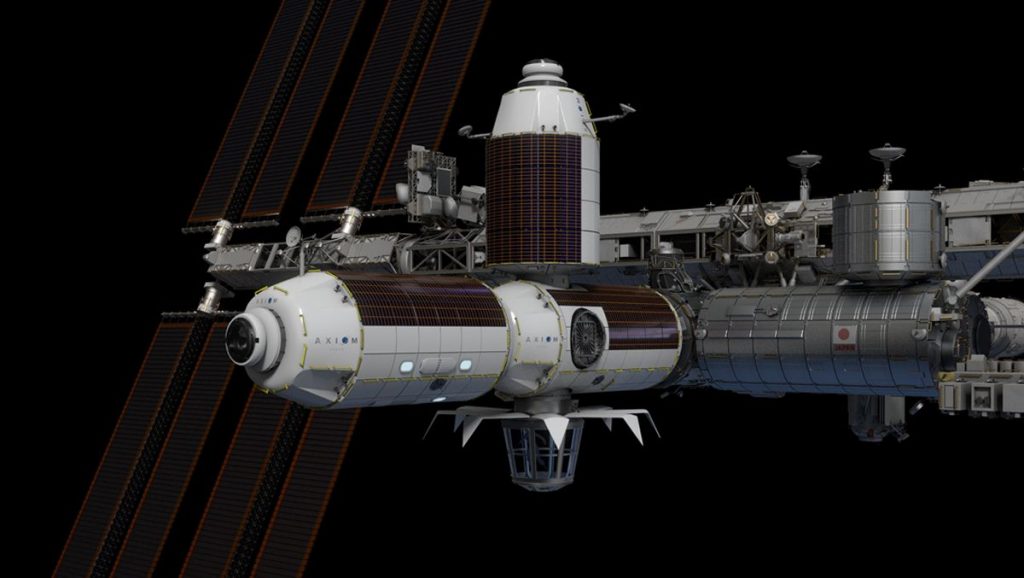

NASA, private companies count on market demand for future space stations after ISS (Image Credit: Space.com)

Senior officials from companies selected by NASA to develop new low Earth orbit space stations are eager for market input to drive development.

Space industry leaders gathered in Washington, D.C. last week for NASA’s 11th annual International Space Station Research and Development Conference (ISSRDC). A panel in the morning of July 26 included top representatives from four companies selected by NASA to design and develop commercial space stations in low Earth orbit (LEO).

About 20% of JSC’s current workforce is utilized to run the ISS, with another 15% working on commercial crew, according to JSC Director Vanessa Wyche. With such a heavy weight of its focus on ISS, NASA decided to lean into its commercial contract model, and selected private companies to design and develop replacement space stations for the agency’s aging orbital laboratory. This not only opens the door for a wider array of commercial accessibility to LEO, but also frees up some of NASA’s resources for the space agency’s shifting focus to interplanetary exploration through the Artemis program and beyond.

Related: Private space stations are coming. Here’s what NASA astronauts want to see

NASA and the companies it selected are counting on a booming market of commercial interest in LEO. “Our main goal is to have a platform post-ISS that can provide our needs, but can move us into the position where commercial innovation can happen. Different things can start happening in space that wouldn’t happen on a government facility,” NASA’s Angela Hart said during Wednesday’s panel.

Hart serves as the program manager for the agency’s Commercial LEO Development Program Office, at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, which was created to ensure a continuous presence of U.S. astronauts in LEO following the operational end of the International Space Station (ISS), currently scheduled for 2030.

Hart is quick to point out the tremendous amount of research and innovation already to come out of the last decade of science aboard the ISS, its contribution to humanity on Earth, and our understanding of what it takes to explore the stars. Because of these contributions, Hart is adamant that NASA continues to have a presence in LEO.

“A platform to be able to continue to do the science and other research that we’re doing on ISS will absolutely be needed for exploration,” Hart said.

In January, 2020, NASA selected Axiom Space to construct the first commercially-developed module for the ISS. In December, 2021, NASA selected three more companies to develop their own commercial LEO destinations (CLDs) — Nanoracks, Northrop Grumman, and Blue Origin, which partnered with Sierra Space. Senior officials from each sat together with Hart during the July 26 ISSRDC panel to discuss their different space station designs, and their expectations for the commercialization of LEO.

Christian Maender, executive vice president for in-space solutions at Axiom, says the company’s first module is on track for delivery to the ISS in 2024, with a second to be put in place during 2025. “We’re putting platforms in place that we can start business on immediately,” Maender told the panel. “At Axiom … we’re building what we believe to be a foundational infrastructure for this LEO commercialization effort,” he said.

Axiom’s plan is to incrementally add modules to its first at a pace of about one a year, according to Maender. The first two will function as habitats with bays for various payload services. The third module will bring research and manufacturing capabilities to the group, and the fourth will mark the Axiom station’s departure from its ISS berth. “Ultimately, we will bring what we call our ‘power tower,’ which will generate all the power and thermal heat rejection that we need to become independent,” Maender explained.

Axiom may be getting to orbit first, but Rick Mastracchio, director of strategy and business development at Northrop Grumman, points out his company already has the infrastructure. “We’re building this based on a lot of the heritage systems,” Mastracchio said of the Northrop Grumman space station. He listed the company’s Cygnus spacecraft, Halo cislunar habitat currently in development, and Mission Extension Vehicle, which Northrop Grumman offers to prolong satellite lifespans. “We have all the pieces, we have the facilities, we have the staff, we have the systems, we have the experience,” Mastracchio said, “so it’s a small step for us to build a space station.”

Sierra Space also has some experience building spacecraft. Their Dream Chaser space plane is scheduled to launch on its first cargo mission to the ISS next year. They’ve teamed up with Blue Origin and a handful of other commercial contributors for a space station they’re calling Orbital Reef. Sierra Space President Janet Kavandi says the first two inflatable “Life modules” used as the space station’s core are on schedule for a 2027 debut, “to allow for plenty of time to transition away from ISS, if the end of ISS is still considered to be 2030.” She also noted a recently successful ‘burst-test’ of the module that ‘well exceeded’ requirements.”

Kavandi describes Orbital Reef as modular, and expandable to fit and grow with customer needs. She says the company’s intent is to “just keep adding as business grows, and make it as big as business demands.”

Sierra Space’s business model also includes “professional astronauts” aboard Orbital Reef to maintain the facility, “so that the researchers and the manufacturers that come onboard can fully concentrate on their work,” Kavandi told the panel. Typically, research conducted aboard the ISS is completed by the same astronauts performing station maintenance. A recent exception is the Axiom-1 mission from earlier this year.

Axiom-1 was the first mission to the ISS consisting of all private citizens. The mission lasted 17 days, and the passengers were able to perform 26 different science investigations during their time aboard the station. Axiom-1 represented a major milestone for the commercialization of space, and serves as a model for how things might operate once commercial space stations reach orbit.

Sierra Space and its partners want to lower the barrier of extensive engineering training and other astronaut flight-prep typically needed before launching to space by “providing professional crews that will maintain a station, and then allowing the researchers … to go up themselves and do their research or their manufacturing,” Kavandi said, “we can allow them to do that, and they get 100% of their time.”

Kavandi also addressed other limitations the ISS creates for commercial space. “There’s just not a lot of space on [the ISS] for people to actually do work that you can make a profit from,” she said, “and commercial space, if it’s not profitable, won’t be sustained. So we have to provide the space to allow people now to take the research, the results of the research, the things that look promising, and actually do something with that research.”

Amela Wilson, CEO of Nanoracks, says her company’s Starlab space station is a “natural extension” to their history of working in collaboration with NASA aboard the ISS. “We realized that the ISS will not be there forever, and we felt obligated with our knowledge and experience to actually build [a space station] and make sure that we enable the research…to continue without skipping a beat,” Wilson told the panel.

Nanoracks is aiming to launch the first Starlab around 2027 or 2028, according to Wilson, but expects to launch multiple “purpose-built” stations over time. “Maybe some for science, technology, biology, material sciences and so forth,” Wilson listed, “but others maybe for on-orbit manufacturing. Space manufacturing may require a different environment. Some other ones may be used for entertainment or hospitality. The sky’s — well, no. Space is the limit,” Wilson joked.

Whatever the limit, the space industry bigwigs on the panel all expressed eagerness to find out just what exactly their company’s space stations could be used for. “Building a space station is easy,” Rick Mastracchio said. “Building the business is the hard part, and that’s why we’re trying to really concentrate a lot on customers, and trying to figure out what it is they want,” he explained. “What do you need? What facilities, what capabilities do you need? Mass, volume, power, et cetera, et cetera? So we’re collecting that input right now…and giving that to our technical team to fully define what our space station is going to be.”

Maender agreed, echoing, “the harder part is going to be building some of these markets.” Maender sees Axiom’s station as a trailblazer for the rest — poised, hopefully, to set in motion a booming demand for LEO access. “Axiom station is going to be there earlier than some of these other platforms,” Maender said. “We get an opportunity and a privilege, but also a responsibility to be a catalyst for some of these markets that need to be grown.”

Orbital Reef is also being designed with the future in mind. Kavandi said Sierra Space is trying “to provide as much opportunity for as many diverse customers as possible… We’re giving opportunities for not just diversity with different types of science and research that we can do, but also for countries that have never flown in space before… Offering those diverse capabilities is challenging, but I think it’s what the world demands of the next version of the space station.”

“Market development is certainly key, and the nations that make the biggest efforts to invest in building their space economies are the countries that are going to get the greatest benefit from those markets,” Maender said to the panel. His and other panelists’ reiterated requests for market input and interest felt both like a sales pitch, and a bit like a plea at times. NASA’s model for these new CLDs doesn’t have the agency fully funding any singular company’s design.

“It’s very clear NASA is not going to be footing the whole bill of the space station. We expect them to have other customers and other business interests,” Hart said during the discussion. She told the group one of the goals for NASA’s commercial LEO development program office is to ensure the space agency “doesn’t become a barrier” to the commercial industry. Hart stressed the importance for “the way [NASA] thinks business has to be done” not to “stifle the innovation and the things that industry wants to do,” but said doing so is “really hard.”

“The framework of these contract agreements are set up in a way to allow [these companies] to run quickly — a lot faster than our normal, typical development is, and we are absolutely seeing that,” Hart said. Part of that development is being driven by emerging commercial markets, but the other side of manufacturing a space station when you know NASA is going to be a customer, is knowing what NASA is going to want.

Indeed, Hart acknowledges NASA has been slow to respond to requests for specific guidelines and various hardware standardizations. “Everyone wants NASA’s requirements and we are taking our time,” Hart told the panel, “even though it’s very difficult for everybody because everybody wants to know what that final set is going to be. Because we want to make sure that we don’t levy a requirement set that is going to stifle what they’re doing.”

“We’re waiting to see what you guys bring to the table,” Hart told the panel of space industry representatives.

She says NASA is in a “phase one” strategy for CLD development, and considers each of the contracted companies to be in “phase one” as well. “Phase two is when we would put out a firm fixed-price certification and services contract, where we would actually go purchase services from hopefully more than one space station, which is our goal — to have multiple space stations. A minimum of two is our goal,” Hart said.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).