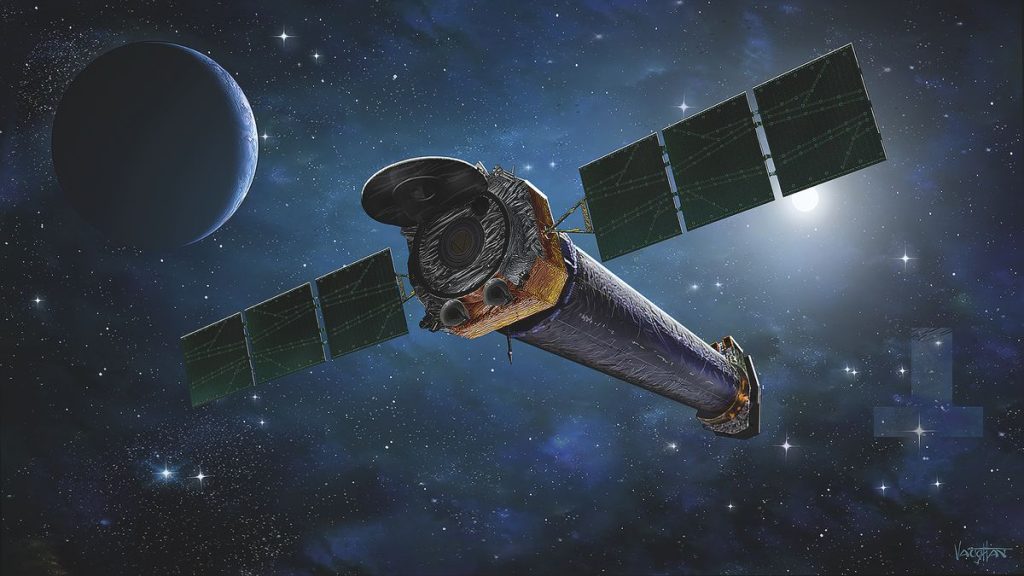

NASA delays budget-cut decision about Hubble and Chandra space telescopes (Image Credit: Space.com)

NASA is delaying making a final decision about potential cost cuts that will determine the fate of the Chandra X-ray Observatory and affect the Hubble Space Telescope’s science program. Although no official word has been given for the reason behind this delay, it seems NASA is keeping its options open until confirming its budget for the new fiscal year.

In what has become a long-running saga, Chandra’s neck remains on the chopping block. Together, the Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory make up 10% of NASA’s astrophysics budget. The two orbiting telescopes are part of NASA’s Great Observatories program, along with the now-defunct Spitzer Space Telescope and the Compton Gamma-ray Observatory. While both Hubble and Chandra are in their twilight years, having launched in 1990 and 1999 respectively, they are both still producing valuable science.

Despite the continued excellence of both Hubble and Chandra, and their being highlighted in the most recent Decadal Survey as being funding priorities, Chandra’s annual budget could be cut by 40%, from $68.3 million to $41.1 million, with further cuts being made each subsequent year until 2029, when its budget would be just $5.2 million. Meanwhile, Hubble faces a 10% cut in its budget from $98.3 million to $88.9 million.

Faced with these potential cuts, NASA convened an independent panel of eight astronomers, the Operations Paradigm Change Review (OPCR), to assess how these cuts could be implemented. The team’s conclusion, delivered in July, was dire: Chandra could not continue to operate on a budget of $41.1 million. It would effectively end the X-ray observatory’s mission. Although NASA does have other X-ray missions, such as the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) and the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER), neither have the all-around capabilities, angular resolution or sensitivity that Chandra has. The most recent decadal survey proposed a new class of mission, called “Probe class” with a budget of a few billion dollars that could be a way forward for a new X-ray mission, but no new X-ray missions to replace Chandra are currently on the drawing board.

In an open letter sent to the heads of NASA’s Astrophysics Division and the Chandra science community in July, David Pooley of Trinity University in Texas, who is the Chair of the Chandra Users’ Committee, slammed NASA’s decision to make the cuts to Chandra.

“The telescope continues to perform exceptionally well and keeps generating cutting edge science,” said Pooley. “Chandra is providing crucial and unique scientific capabilities that will not be replaced by another U.S. telescope for at least a decade, perhaps two.”

The reason for NASA delaying the final decision on the matter is unclear. All government agencies are currently operating on 2024 spending levels, even though the new fiscal year began on Oct. 1, partly because of the upcoming election and the uncertainty that it brings. It would seem that NASA is unwilling to pull the trigger until the agency’s budget is rubber-stamped.

Meanwhile, although the continued operation of the Hubble Space Telescope is not in danger, the proposed 10% cut to its budget would reduce its ability to conduct science. The OPCR suggested three options for how this reduction in funding could be applied. One of those options would be to reduce the funding made available for astronomers in Hubble’s general observer programs. Another would be to remove up to five of Hubble’s nine observing modes, including its infrared ability and possibly its ultraviolet capabilities. Although the infrared regime is now mostly covered by the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA does not currently have another ultraviolet space mission, although UVEX – the UltraViolet Explorer, is planned to launch in 2030.

The final option would be to reduce Hubble’s operational costs, which would involve staff lay-offs that could increase risks to the telescope as there would be fewer experienced members of staff in-house should a major problem arise with the orbiting observatory.

Ultimately, for both space telescopes, the net result could be a decrease in available telescope time for astronomers to do science. For example, if Chandra were to be reduced to only observing transients and multi-messenger astronomy by partaking in joint observing programs with other observatories, it would save $20 million on its budget — but its available observing time would be reduced by half. However, even this last resort would require a higher budget than the $41.1 million currently on the table.

It is possible that new money could still be found for NASA’s overall budget. Currently, for 2025, NASA has been offered $25.434 billion, which accounts for half-a-percent of the total federal budget — but that could still change. If there are no new federal funds forthcoming, another option would be for NASA to take funding from other parts of its science directorate, but this would mean cuts made to other missions instead. Given the furor this would provoke among other corners of the community, it seems an unlikely choice.

So, Chandra heads into 2025 on increasingly choppy waters, its fate perilous and far from determined. Without knowing the exact reason for the delay in announcing what will happen to Chandra and Hubble, it’s hard to say whether we should read too much into it.

“Great Observatories like Chandra are precious,” wrote Pooley in his open letter. “They are national treasures.”