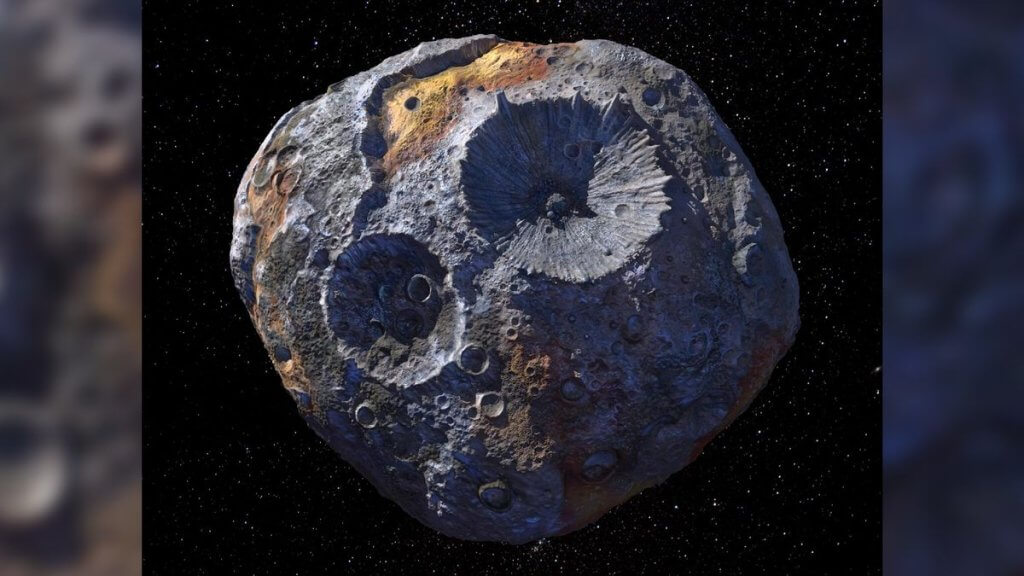

Metal asteroid Psyche has a ridiculously high ‘value.’ But what does that even mean? (Image Credit: Space.com)

You might have heard that the asteroid 16 Psyche, the target of NASA’s upcoming Psyche mission, is worth $100,000 quadrillion. But how can you really pinpoint an asteroid’s monetary value?

Psyche orbits the sun in the main asteroid belt, between Mars and Jupiter. Scientists think the asteroid could be an exposed metallic core of an ancient protoplanet. If the metals on Psyche were on Earth, they would be worth more than the entire world economy, according to an estimate by the Psyche mission’s lead scientist, Lindy Elkins-Tanton.

But, of course, these metals are not on Earth — not even close. Still, the spectacularly high value does point to how exciting and impactful the Psyche mission could be — not only for planetary science but also for the budding asteroid mining industry.

Related: Space mining startups see a rich future on asteroids and the moon

Psyche is an M-type asteroid, meaning it is metallic, though it’s not entirely clear what type of metal it is made of. Spectroscopy, one of the ways scientists determine the composition of celestial objects, splits up light coming off of an object into a spectrum, giving each object a “spectral fingerprint.”

“Unfortunately, metal doesn’t have a unique spectral fingerprint,” Vishnu Reddy, a professor at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona who has published numerous studies on 16 Psyche, told Space.com. “You can tell that something’s metallic, but you can’t specifically tell which metal it is.”

Methods like radar show that Psyche’s surface is highly reflective but don’t reveal what the reflective material is, he said. Many scientists think Psyche’s surface is made mostly of nickel and iron, since those elements tend to be common in asteroids, he added.

Scientists can also use computer simulations, along with the giant impact craters on Psyche’s surface, to determine what the asteroid might need to be made of to survive the collisions that created the craters. Wendy Caldwell, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, told Space.com that some of her most promising results, including the findings of a 2020 study, had the asteroid being made of Monel, a metal that is made mainly of nickel and copper and is thought to be representative of the composition of metallic objects in space. (These simulations also used Monel as the asteroid’s impactor.)

“We can’t definitely say, this is the composition,” Caldwell said. But these models can help scientists identify the materials that may or may not be feasible, she added, and we’ll know better once we get there. Unfortunately, it’s a long wait; the Psyche spacecraft isn’t scheduled to arrive at its target until 2029.

Regardless of what Psyche is made of, it likely contains so much metal that estimating its amount and multiplying it by the current market value yields an unbelievable number, like the $100,000 quadrillion figure, which Elkins-Tanton estimated you could get from mining iron alone.

There are no plans to mine Psyche, nor technology that would allow us to. Even if we could mine Psyche and bring the materials back to Earth, the asteroid is so far away that the cost of doing so would negate their value, Philip Metzger, a planetary physicist at the University of Central Florida, told Space.com.

Nonetheless, some companies, such as AstroForge, already have plans to mine asteroids, Metzger said.

“I do believe that asteroid mining will be a real thing, and it will be profitable,” he said, adding that he believes it’s possible for the necessary technology to be developed within decades. Smaller asteroids, including M-type asteroids, would likely be asteroid miners’ first target, Metzger said .

It’s not only metals such as iron that might be worth mining from asteroids, Metzger said. Asteroids composed mainly of clay contain a lot of water, which could potentially be used to make rocket fuel on off-world settlements. To become profitable, companies also might go straight to trying to mine valuable metals such as platinum.

One of the biggest challenges of asteroid mining will be to find ways to give people around the world access to the resources, Metzger said. Unequal access to resources is already a substantial problem on our planet, and he hopes future industry regulations will help enable more equitable access.

In the far future, we might mine Psyche to provide resources to astronauts bound for far-flung destinations such as Mars. In the short term, however, visiting Psyche is more likely to teach us more about M-type asteroids, thereby preparing future asteroid miners for what might be waiting for them on closer targets.

“The things that we learn about M-class asteroids are going to be applied to M-class asteroids that are closer to the Earth for mining,” Metzger said.