Massive new NASA exoplanet catalog unveils 126 extreme and exotic worlds (Image Credit: Space.com)

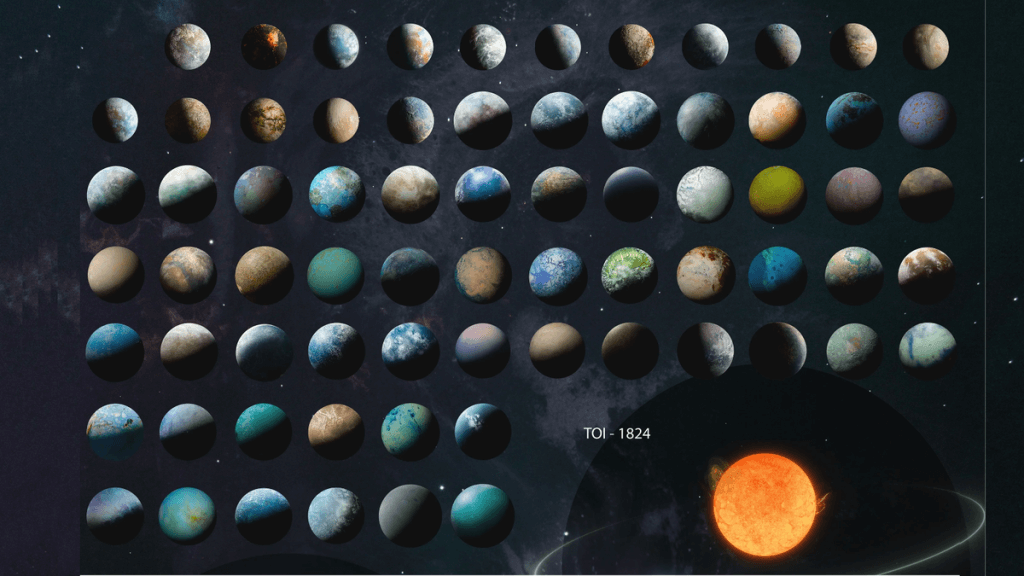

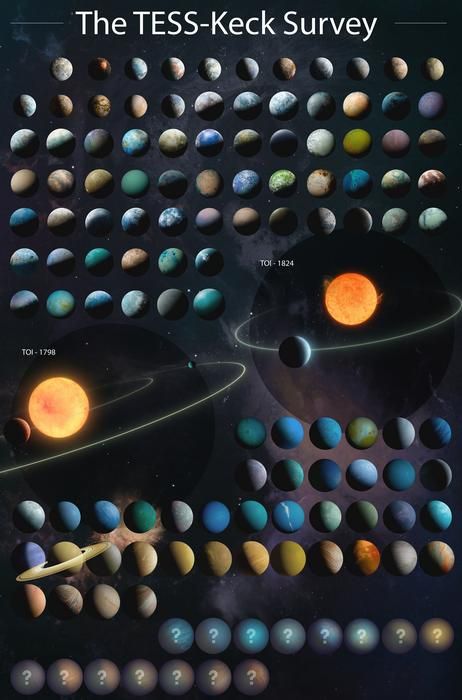

A new catalog of 126 worlds beyond the solar system contains a cornucopia of newly discovered planets — some have extreme and exotic natures, but others could potentially support life as we know it.

The catalog’s mix of planets is further evidence of the wide and wild variety of worlds beyond our cosmic backyard; it even shows that our solar system is perhaps a little boring. Yet, despite these planets being so different than Earth and its neighbors, maybe they can still help us better understand why our planetary system looks the way it does, thus uncovering our place in the wider cosmos.

The catalog of extrasolar planets, or “exoplanets,” was created using data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in collaboration with the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

“With this information, we can begin to answer questions about where our solar system fits into the grand tapestry of other planetary systems,” Stephen Kane, TESS-Keck Survey Principal Investigator and an astrophysicist at the University of California, Riverside, said in a statement.

Related: NASA space telescope finds Earth-size exoplanet that’s ‘not a bad place’ to hunt for life

The new TESS-Keck Survey of 126 exoplanets really stands apart from previous exoplanet surveys because it contains complex data about the majority of planets included.

“Relatively few of the previously known exoplanets have a measurement of both the mass and the radius,” Kane added. “The combination of these measurements tells us what the planets could be made of and how they formed.”

“Seeing red” to measure exoplanet masses

The catalog was built over the course of three years as the team used 13,000 measurements of tiny “wobbles” that planets cause as they orbit their stars and exert a tiny gravitational tug on them. This tug causes a star to move slightly away, then slightly toward, Earth.

When stars are pulled slightly away, this stretches the wavelengths of light they emit, moving them toward the “red end” of the electromagnetic spectrum. When stars move toward Earth, the wavelength of the light they omit is slightly compressed, making it “bluer.”

The exploitation of redshift and blueshift in this way by astronomers is called the “radial velocity method.” Because the strength of the gravitational pull a planet exerts on a star is proportional to its mass, it is a good way of determining mass. Thus, the radial velocity method allowed Kane and team to determine the mass of 120 confirmed exoplanets and six exoplanet candidates.

“These radial velocity measurements let astronomers detect and learn the properties of these exoplanetary systems,” Ian Crossfield, University of Kansas astrophysicist and catalog co-author, said. “When we see a star wobbling regularly back and forth, we can infer the presence of an orbiting planet and measure the planet’s mass.”

Excitingly, some of the 126 exoplanets in the TESS-Keck Survey could deepen astronomers’ understanding of how an array of diverse planets form and evolve.

A strange super-Earth, a sub-Saturn and more!

Two of the new planets featured in the TESS-Keck Survey orbit a sun-like star called TOI-1386, which is located around 479 light-years away.

One of these exoplanets has a mass and width that put it somewhere between the solar system gas giant Saturn and the smaller, less massive ice giant Neptune. That makes this planet, designated TOI-1386 b, a “sub-Saturn” planet and a fascinating target for planetary scientists.

“There is an ongoing debate about whether sub-Saturn planets are truly rare, or if we are just bad at finding planets like these,” discoverer and UCR graduate student Michelle Hill said in the statement. “So, this planet, TOI-1386 b, is an important addition to this demographic of planets.”

At a distance from its parent star, equivalent to around 17% of the distance between Earth and the sun, TOI-1386 b takes just 26 Earth days to complete an orbit.

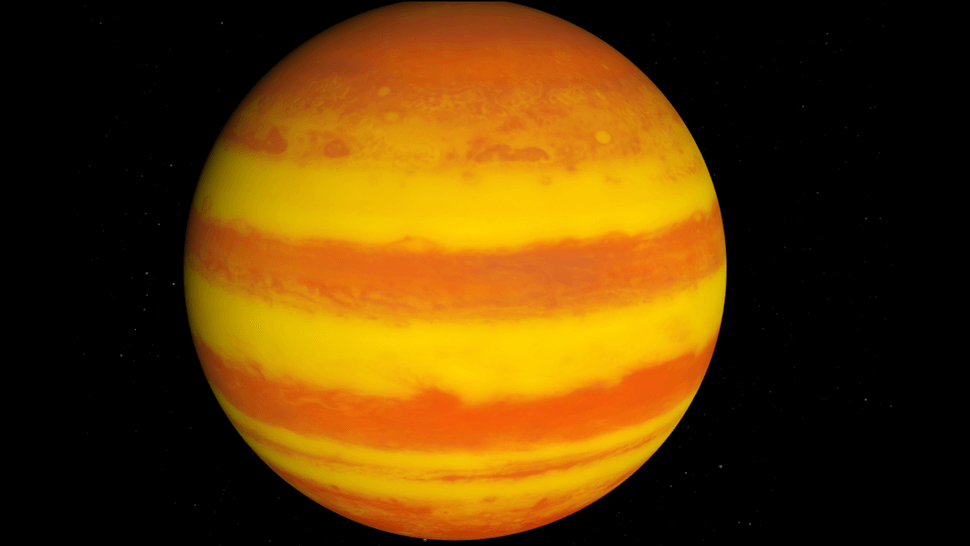

Its newly discovered closest neighbor is a bit more leisurely. TOI-1386 c is a puffy gas giant that is about as wide as Jupiter, but with only 30% of the mass of the largest planet in the solar system. It sits around 70% of the distance between Earth and the sun from its parent star, and has a year that lasts about 228 Earth days.

Another fascinating world among this batch of exoplanets is around half the size of Neptune, with over ten times the mass of Earth, orbits TOI-1437 (also known as HD 154840), and is located some 337,000 light-years away.

Designated TOI-1437 b, the sub-Neptunian planet orbits its star at around 14% of the distance between Earth and the sun, and has a year lasting around 19 Earth days. Discovered by TESS via the tiny dip in the light it causes as it crosses the face of its star, TOI-1437 b is one of the few sub-Neptunes known to transit its star that has a well-defined mass and radius.

TOI-1437 b also highlights a curious absence in our cosmic backyard.

“Planets smaller than Neptune but larger than Earth are the most prevalent worlds in our galaxy, yet they are absent from our own solar system,” discoverer and UCR graduate student Daria Pidhorodetska said in the statement. “Each time a new one is discovered, we are reminded of how diverse our universe is and that our existence in the cosmos may be more unique than we can understand.”

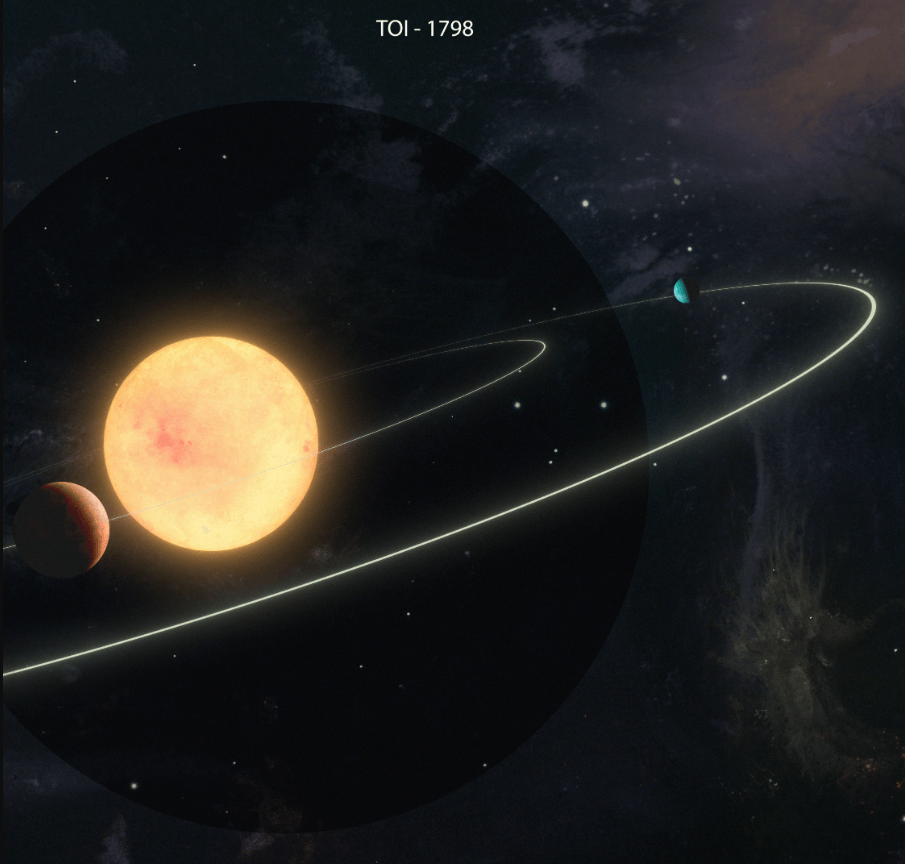

Another interesting exoplanet detailed for the first time in this new catalog is TOI-1798 c, a super-Earth that orbits an orange dwarf star so closely its year lasts just about 12 Earth hours.

“One year on this planet lasts less than half a day on Earth,” study lead author Alex Polanski, a University of Kansas physics and astronomy graduate student, said in the statement. “Because of their proximity to their host stars, planets like this one are also ultra hot — receiving more than 3,000 times the radiation that Earth receives from the sun.”

This makes the planetary system TOI-1798, which also hosts a sub-Neptune planet that completes an orbit in around eight days, one of only a few star systems known to have an inner super-Earth planet with an ultra-short period (USP) orbit.

“While the majority of planets we know about today orbit their star faster than Mercury orbits the sun, USPs take this to the extreme,” Pidhorodetska added. “TOI-1798 c orbits its star so quickly that one year on this planet lasts less than half a day on Earth. Because of their proximity to their host star, USPs are also ultra hot — receiving more than 3,000 times the radiation that Earth receives from the sun. Existing in this extreme environment means that this planet has likely lost any atmosphere that it initially formed.”

The release of the TESS-Keck Survey’s Mass Catalog means that astronomers now have a way of exploring in depth the work of TESS, which launched in April 2018, and gauging how it has changed our understanding of exoplanets.

With thousands of planets from the TESS mission alone still yet to be confirmed, releases of exoplanet catalogs like this one are set to become more common.

“Are we unusual? The jury is still out on that one, but our new mass catalog represents a major step toward answering that question,” Kane said.

The exoplanets are described in the Thursday (May 23) edition of The Astrophysical Journal Supplement.