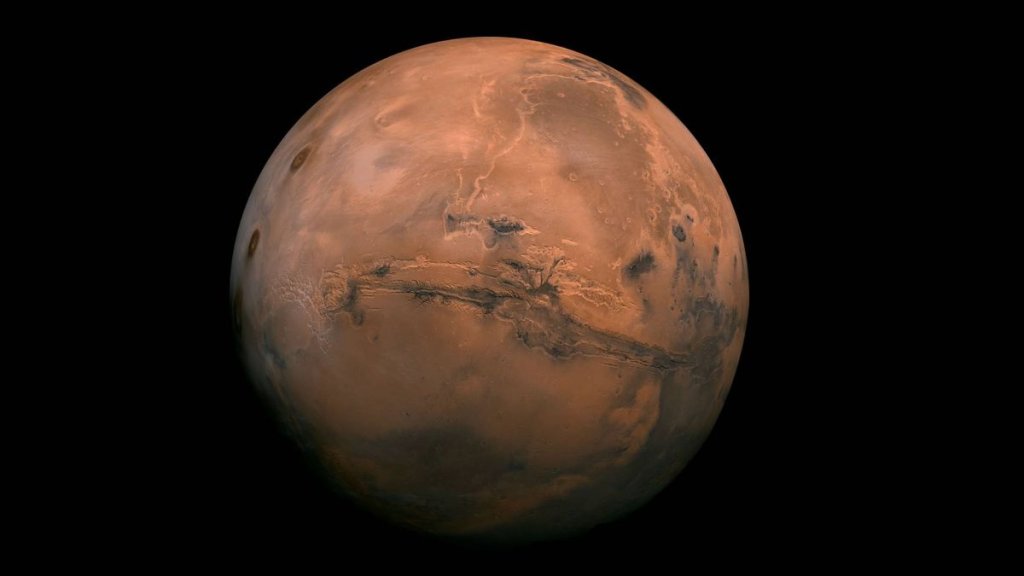

Mars is an asteroid punching bag, NASA data reveals (Image Credit: Space.com)

Meteorite impacts pepper Mars at a rate up to 10 times more frequent than previous estimates, according to two new research papers that identified the seismic shock waves of these impacts detected by NASA’s now-defunct Mars InSight lander.

The new rate is staggering. According to the findings, between 180 and 260 impacts per year occur on the Red Planet, and these objects can get at least as large as basketballs, procuring eight-meter (26-foot) craters in the ground. In all, the impact rate is between two and 10 times higher than predicted, depending upon the size of the impactor. And some of the new impacts detected by InSight were big: For example, one of the studies reports two large impacts, which happened 97 days apart, that were significant enough to each excavate a crater the size of a football field.

“This size impact, we would expect to happen maybe once every couple of decades, maybe even once in a lifetime, but here we have two of them that are just over 90 days apart,” Ingrid Dauber of Brown University, who led one of the studies, said in a statement.

Dauber is skeptical that these impacts are just coincidence, and suggests it is more likely that the Mars impact rate is just generally higher than planetary scientists realized.

Related: Solar storm douses Mars in radiation as auroras flicker in the Red Planet sky

Both studies utilized the seismometer instrument, SEIS, on InSight (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) to detect the impacts. InSight recorded seismic data for four years, during which time SEIS was active on the surface of Mars (between December 2018 and December 2022). Teasing out the seismic shockwave of an impact from all the other seismic movements within the Red Planet isn’t easy, so Dauber’s team compared the seismic data with images of apparently new craters seen from orbit by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to connect the tremors with actual impacts.

From MRO’s images, Dauber’s team identified eight new impact craters that had created “marsquakes: detected by SEIS. Six of these craters were in the locality around InSight’s landing site in Elysium Planitia. The two larger impacts that were 97 days apart formed craters that are farther afield. These two events are the largest fresh impacts seen to take place on Mars in the history of our robotic exploration of the Red Planet.

The second study, led by Natalia Wojcicka of Imperial College London, suggests that between 280 and 360 basketball-size impactors occur every year based solely on the data from SEIS. However, the estimated impact rate in each paper, calculated independently from each other using slightly different methods, corroborates one another, which adds to the results’ veracity.

Detecting impacts this way is an important new ability because, previously, planetary scientists could only find new impacts by comparing before and after images of the Martian surface from orbit and seeing whether any new craters had appeared. This, as you may imagine, was very inefficient. Seismic data adds a new dimension to efforts to measure these impacts. Further, the findings also have consequences that could percolate throughout our studies of all the other solid bodies in our solar system.

Planetary surfaces don’t come with a receipt saying how long ago they formed, or when they were last covered by lava. Instead, scientists must calculate surface ages based on how many craters cover those surfaces; the more craters there are, the older the surface must be. We can see a classic example of this on our moon. The ancient lunar highlands, which are about as old as the moon itself, are littered with craters, whereas the lunar mare, which are volcanic plains up to a billion years younger, have much fewer craters.

However, being able to date planetary surfaces relies on scientists having an accurate handle on impact rates, and the new data from Mars suggests that, well, perhaps we don’t. If the Mars impact rate is higher than we thought, then some planetary surfaces may be younger than previously determined, because they could have accrued their craters over a shorter time period.

“By using seismic data to better understand how often meteorites hit Mars and how these impacts change its surface, we can start piecing together a timeline of the Red Planet’s geological history and evolution,” said Wojcicka in a statement. “You could think of it as a sort of ‘cosmic clock’ to help us date Martian surfaces and, maybe further down the line, other planets in the solar system.”

Dauber goes further, saying that not only does the higher impact rate “hold implications for the age and evolution of [Mars’] surface,” but that “This is going to require us to rethink some of the models the science community uses to estimate the age of planetary surfaces throughout the entire solar system.”

Dauber’s team published their findings on June 28 in the journal Science Advances, while the findings from Wojcicka’s team were published at the same time in the journal Nature Astronomy.