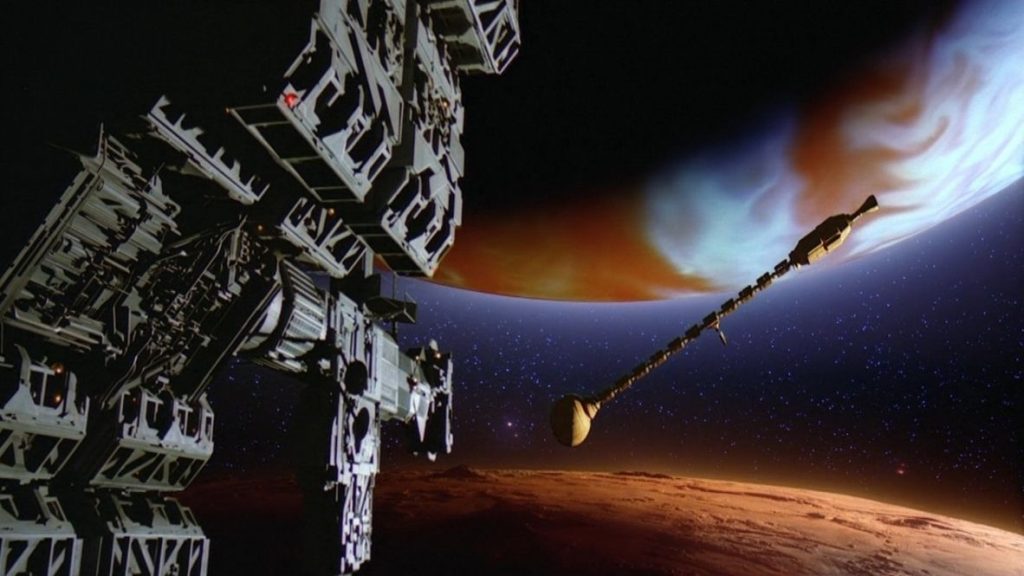

Looking back at ‘2010’, the criminally-underrated sequel to ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (Image Credit: Space.com)

“2001: A Space Odyssey” offered more questions than answers, and the movie’s ambiguous and metaphysical final act has subsequently been debated for well over half a century. But 40 years ago, in December 1984, a movie sequel had a decent stab at explaining some of the mysteries Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic — with its psychedelic imagery and giant space babies — left behind.

“2010” (subtitled “The Year We Make Contact”) was written and directed by Peter Hyams, who’d established himself with 1978 conspiracy thriller “Capricorn One”. When he was approached about a “Space Odyssey” follow-up, however, he was reluctant to follow in the footsteps of one of the 20th century’s greatest directors.

“When I was asked to do the film I said absolutely not,” Hyams told SFX magazine in 2006. “I didn’t want to go near it. Stanley Kubrick was not a filmmaker, he was an icon. I said I’d do it only if Kubrick agreed to me doing it.” (He did.)

“I figured good, bad or indifferent, the worst thing I could do would be to try to replicate ‘2001’, so I set out to make a film that was so different in attitude, in look, in pace, in sound — a film that was much more emotional, much more visceral, so that you couldn’t really compare them.”

The opening of “2010” is effectively a checklist of viewer questions, as a report into the failed Discovery mission to Jupiter emphasizes a baffling quantity of “unknowns”. Where did those freaky black monoliths come from? Unknown. Why did creepy computer HAL 9000 have a critical malfunction that killed most of the crew? Unknown. Why did Dave Bowman send that bizarre final transmission — “My God, it’s full of stars!” — and where is he now? Yes, you guessed it, unknown.

Former NCA chairman Heywood Floyd (“Jaws”‘ Roy Scheider, in a role originated by William Sylvester in “2001”) takes the lead. For some reason (another unknown), Discovery is being pulled towards Io, and will crash into the moon within a couple of years. With the clock ticking, Floyd puts together a plan for him and a couple of other experts — Discovery designer Walter Curnow (John Lithgow) and HAL creator R Chandra (Bob Balaban) — to hitch a ride on a Soviet spacecraft that’ll make it into space long before the in-development Discovery 2.

There is an additional problem, however. In “2001” author Arthur C Clarke’s sequel novel “2010: Odyssey Two” (published in 1982), the Americans and Soviets worked together. But, with Clarke’s approval (the two men corresponded regularly via an early-80s precursor to email), Hyams saw an opportunity to ratchet the tension by having the two Cold War superpowers at loggerheads. A military stand-off in Central America means World War III could break out at any time.

This change would prove indicative of Hyams approach. Where Kubrick’s movie is clinical, emotionally distant, and tackles ambitious themes about the evolution of our species, “2010” is rather more interested in individual humans than humanity as a whole. Floyd and his Soviet counterpart Tanya Kirbuk (Helen Mirren) are just as concerned about family back home as finding chlorophyll on the moon of Europa. In one memorable scene, a young Soviet cosmonaut comes to Floyd for reassurance when the Leonov executes a dangerous braking maneuver.

It’s clear that Hyams paid close attention to the sci-fi movies that landed after Kubrick’s odyssey. The interior of the Leonov and the characters’ dress sense borrows heavily from “Alien“, while the visual effects were supervised by Richard Edlund, one of the Industrial Light & Magic pioneers who’d worked on the original “Star Wars” trilogy. Hyams also opted to have audible sound in outer space — much more galaxy far, far away than the eerie, scientifically accurate silence of “2001”.

Not that he ditched the physics entirely… In a 1984 interview with film critic John C Tibbetts, Hyams pointed out that “it’s not a film about the distant future”, and that “It was done with a pool of knowledge from Jet Propulsion Labs, from Boeing Aerospace, from Arthur C Clarke. This is pretty close to the technology that we think’s going to be around. It is generally believed that by the year 2010 we will be exploring planets in our solar system.”

SPOILERS AHEAD: LOOK AWAY IF YOU DON’T WANT TO RUIN THE ENDING.

IT’S ON YOUTUBE FOR FREE, GO WATCH IT AND THEN COME BACK.

Although the movie’s predictions of interplanetary exploration ultimately proved wide of the mark, the continuation of HAL 9000’s story remains pertinent. Thanks to a bold retcon, it turns out that the Discovery’s digital antagonist-in-chief wasn’t evil after all — arguably a disappointment to anyone who’d elevated the red-eyed computer to the pantheon of great sci-fi villains.

Instead, we learn the US government had gone over Floyd’s head, giving HAL information about the Jupiter monolith that forced him to lie to the humans in his care. This contradiction in his programming caused him to behave irrationally, ultimately resulting in the deaths of four crew members before Bowman pulled the plug. The lesson? Even the most powerful AI in the solar system is only as good as the humans issuing the commands.

But HAL is the least of Floyd’s worries. Not only has an escalation of US/USSR hostilities led to the Americans’ expulsion from the Leonov, he’s also received a mysterious warning imploring him to leave Jupiter within two days. The sender? A being that calls itself Dave Bowman.

Bringing Keir Dullea back to reprise his role as Bowman — along with Douglas Rain as the voice of HAL — is arguably Hyams’ biggest masterstroke. He’s the connective tissue between the two movies, and — whatever his current plane of existence — provides a human face for the “something wonderful” happening outside.

As Bowman persuades Kirbuk to defy their government’s orders by mounting a joint escape plan — sacrificing Discovery and HAL in the process —monoliths appear on Jupiter’s surface and start to multiply at an exponential rate. The planet subsequently collapses to be reborn as a new star, as HAL broadcasts a new message dictated by Bowman: “All these worlds are yours except Europa. Attempt no landing there. Use them together. Use them in peace.”

You can enjoy both “2001” and “2010” in isolation, but there’s no doubt they also enhance each other. Thanks to its audacious ambition and technical brilliance, “2001” remains one of the most ground-breaking works in sci-fi history. No sequel was ever going to repeat that but, by taking a more conventional approach to a story of vast scope, “2010” proves to be the ideal companion piece.

It doesn’t have all the answers, and nor should it. The source of the monoliths remains unknown (you need to read Clarke’s novels for more about that), and yet — even though it’s never stated explicitly on screen — it’s clear they have a major role to play in the development of life on Earth… and elsewhere.

In the end, the closing shot of a monolith on a Europa now teeming with life — backed by the familiar notes of Richard Strauss’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” — feels like the perfect conclusion to the story. Which is probably a good thing, seeing as Hyams “never considered” adapting Clarke’s other sequels, “2061” and “3001”. “I did ‘2010’ and I felt I got away with it,” he told Empire in 2014. “If you fall off a building and you land on your feet and you’re okay, you don’t necessarily want to go and try it again.”

“2010: The Year We Make Contact” is available to watch for free on YouTube movies. It’s also available to rent and buy on Apple, Amazon, and other VOD services in the US and UK.