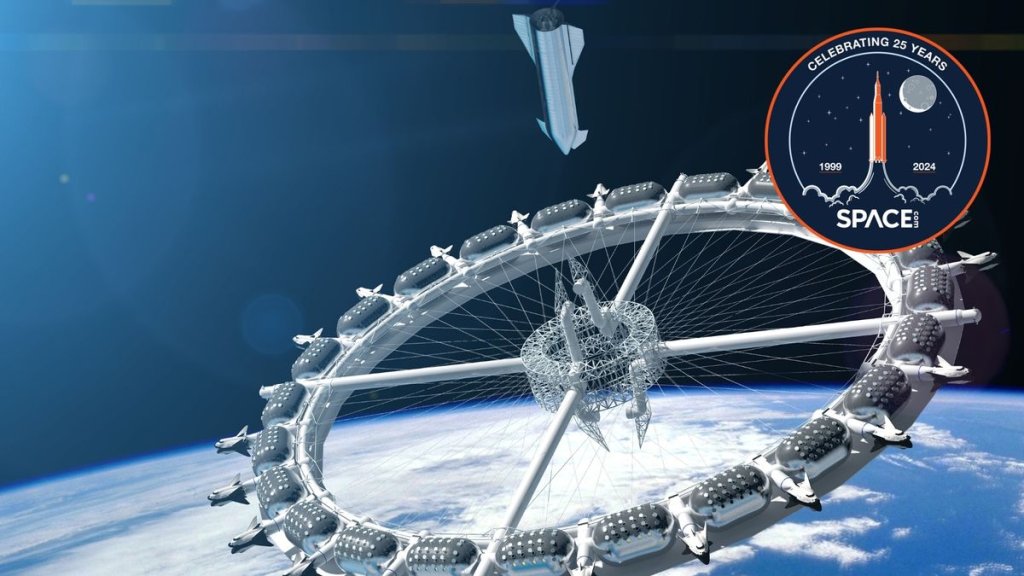

Looking ahead to the next 25 years of private space stations (Image Credit: Space.com)

Humans have occupied low Earth orbit (LEO) over the past half century thanks to the Salyut, Skylab, Mir and Tiangong programs and, of course, the International Space Station (ISS). Aside from providing incredible views of Earth, these space stations have proved that humans can live and work in space while bringing unique lessons about microgravity and the cosmos. They have taught us about the challenges of living in microgravity and the fragility of life beyond our planetary cradle.

But shifting dynamics in the space industry are set to usher in a new era of private space stations tasked with continuing this legacy. The ISS — a decades-long, multinational grand endeavor of cooperation and technological feats — is winding down and could be decommissioned around 2030.

In turn, private companies — including SpaceX, Blue Origin, Planet, Rocket Lab, Virgin Galactic, Axiom Space and Sierra Space — are poised to give rise to a new era of commercial space stations.

Related: NASA looks to private outposts to build on International Space Station’s legacy

“In the short term, commercial space stations are an essential next step to fill the void left by the impending decommissioning of the ISS,” said Lauren Andrade, a spokesperson for the Beyond Earth Institute. “Beyond that, commercial space stations offer a flexibility and capital that government-run projects simply do not possess.”

Blue Origin — together with companies such as Redwire, Sierra Space and Boeing — is building Orbital Reef, a mixed-use business and science park in LEO. The space station will be a scalable, modular outpost for research, manufacturing, tourism and more. Its main habitat will contain 10 crew cabins.

“Commercial space stations open more avenues for both government and private actors to engage in space activities,” Andrade told Space.com.

Both the scope of activities and the modules themselves will be expanded. Orbital Reef will feature Sierra Space’s inflatable Large Integrated Flexible Environment (LIFE) habitat, which will be packed into a New Glenn rocket payload fairing but then be expanded once in orbit. Such a design will provide much greater volume than discrete, rigid ISS modules launched by the now-retired NASA space shuttle and Russian launch vehicles.

Sierra Space said in 2023 that it aims to launch a pathfinder for LIFE around the end of 2026. That module will have a volume of 10,600 cubic feet 300 cubic meters). The company has also proposed a larger, 49,440-cubic-foot (1,400 cubic m) module. In comparison, the Kibo module, the largest single ISS module, has a volume of 5,474 cubic feet (155 cubic m).

As part of the transition to a new generation of space stations, Axiom Space hopes to send its first commercial module to the ISS by 2026.

Both Axiom Space and Blue Origin have received support for these initiatives from NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Development Program. The Starlab space station — a project involving Nanoracks, Voyager Space and Lockheed Martin — also won a NASA award and could come as soon as 2028.

The plan is for NASA to be just one of a number of customers, rather than the sole backer. Indeed, another interested party is the European Space Agency, which has signed a memorandum of understanding with Voyager Space and Airbus for Starlab. This illustrates strong early interest, but more and diverse commercial partners will be wanted. Other players include California-based startup Vast, which plans to launch its first private station, Haven-1, around mid-2025 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

Even if there is a gap between the decommissioning of the ISS and commercial stations getting into orbit, the Tiangong space station will ensure there is a continuing presence in space. China’s three-module orbital outpost was completed in 2022 and now hosts crews of three astronauts for six months at a time. In addition, the country is already looking at commercial opportunities for Tiangong — for example, by expanding the outpost with new modules and hosting commercial and tourism missions.

Expansion beyond LEO

International projects will also expand beyond LEO. Construction on NASA’s moon-orbiting Gateway space station will soon begin in lunar orbit as a basis for future moon exploration. The space station will provide a human habitat beyond LEO for the first time and will involve commercial partners.

Because Gateway will orbit beyond Earth’s protective magnetic field, it will face a range of additional challenges. These include higher levels of radiation, which threaten both electronics and astronauts, as well as a longer journey time, higher launcher demands, and greater communications and power requirements.

Artemis 4, which is currently scheduled for 2028, will be the first mission to send astronauts to Gateway. The astronauts will live and work aboard the Habitable and Logistics Outpost, which is currently slated to launch in 2025, and NASA aims to add a second habitable module before the first crewed mission arrives.

The emergence of commercial space firms and the expansion of our horizons to the moon could see these companies contributing to lunar exploration. Lunar orbit and surface habitats, LEO tech and moon exploration.

“As we have seen already with the expansion of the commercial space sector, I believe the future of commercial space stations is one of more flexibility, more rapid advancement,” Andrade said, “and, at its core, a step toward breaking down the hurdles that limit human activity in space.”

The next 25 years promises significant advancements in space exploration, driven by the ingenuity and ambition of private companies. With the right support and levels of engagement and interest, these will be the new orbital homes for research, innovation, business and international cooperation.