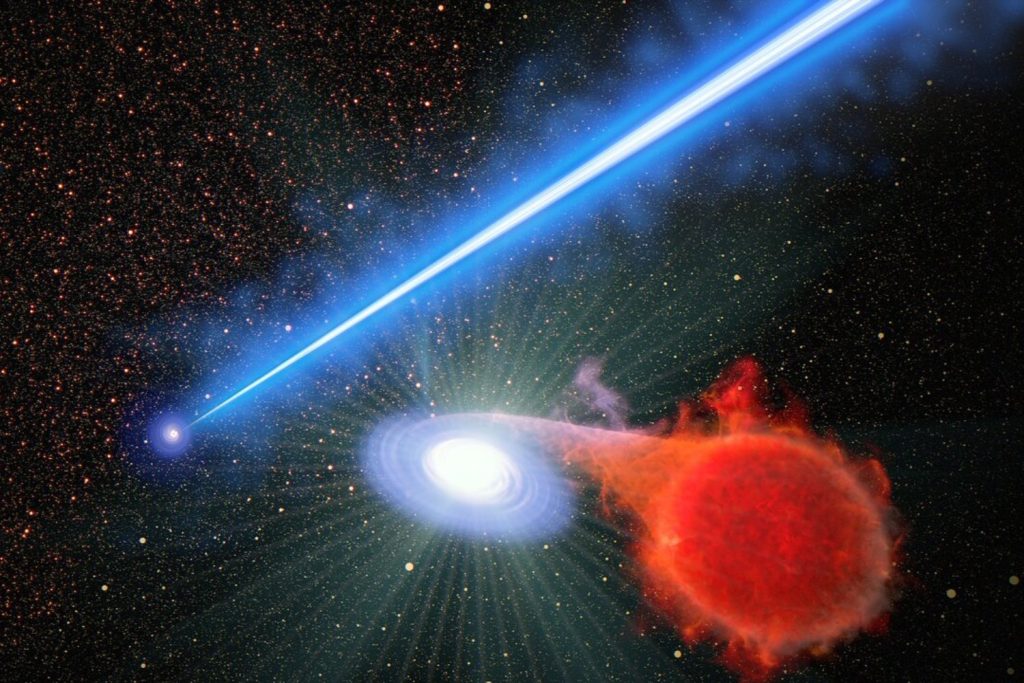

Jets From Black Holes Cause Stars to Explode, Hubble Reveals (Image Credit: Gizmodo-com)

Is there anything more awesome in space than black holes, the phantasmal, jet-spewing regions of spacetime that are so densely packed with matter that they collapse under their own gravity? Actually, yes: Some of these black hole jets seem to cause stars to explode.

These stars are not in the direct paths of the jets, but close enough to the near-light-speed particle beams that it causes them to erupt. The stars in question are white dwarfs—burnt-out shells of stars that take on hydrogen from their companion star. Once the dwarfs have about a mile-thick layer of hydrogen on their surfaces, the layer explodes off the star and the cycle repeats.

“We don’t know what’s going on, but it’s just a very exciting finding,” said Alec Lessing, an astrophysicist at Stanford University and lead author of a new study describing the phenomenon, in an ESA release.

In the recent work—set to publish in The Astrophysical Journal and is currently hosted on the preprint server arXiv—the team studied 135 novae in the galaxy M87, which hosts a supermassive black hole of the same name at its core. M87 is 6.5 billion times the mass of the Sun and was the first black hole to be directly imaged, in work done in 2019 by the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

The team found twice as many novae erupting near M87’s 3,000 light-year-long plasma jet than elsewhere in the galaxy. The Hubble Space Telescope also directly imaged M87’s jet, which you can see below in luminous blue detail. Though it looks fairly calm in the image, the distance deceives you: this is a long tendril of superheated, near-light speed particles, somehow triggering stars to erupt.

Though previous researchers had suggested there was more activity in the jet’s vicinity, new observations with Hubble’s wider-view cameras revealed more of the novae brightening—indicating they were blowing hydrogen up off their surface layers.

“There’s something that the jet is doing to the star systems that wander into the surrounding neighborhood. Maybe the jet somehow snowplows hydrogen fuel onto the white dwarfs, causing them to erupt more frequently,” Lessing said in the release. “But it’s not clear that it’s a physical pushing. It could be the effect of the pressure of the light emanating from the jet. When you deliver hydrogen faster, you get eruptions faster.”

The new Hubble images of M87 are also the deepest yet taken, thanks to the newer cameras on Hubble. Though the team wrote in the paper that there’s between a 0.1% to 1% chance that their observations can be chalked up to randomness, most signs point to the jet somehow catalyzing the stellar eruptions.

These are heady times for black hole jets, which are sometimes overlooked—despite their superlative physics—when we discuss black holes. Just last week, a different team of researchers announced the discovery of the longest black hole jets yet known, which extend some 23 million light-years out from their black hole. In other words, those black hole jets are as long as 140 Milky Way galaxies lined up end-to-end.