James Webb Space Telescope spots faintest galaxy yet in the infant universe (photo) (Image Credit: Space.com)

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has caused quite a stir since it got up and running last summer, revealing a slew of contenders for the title of “oldest galaxy we’ve ever seen.”

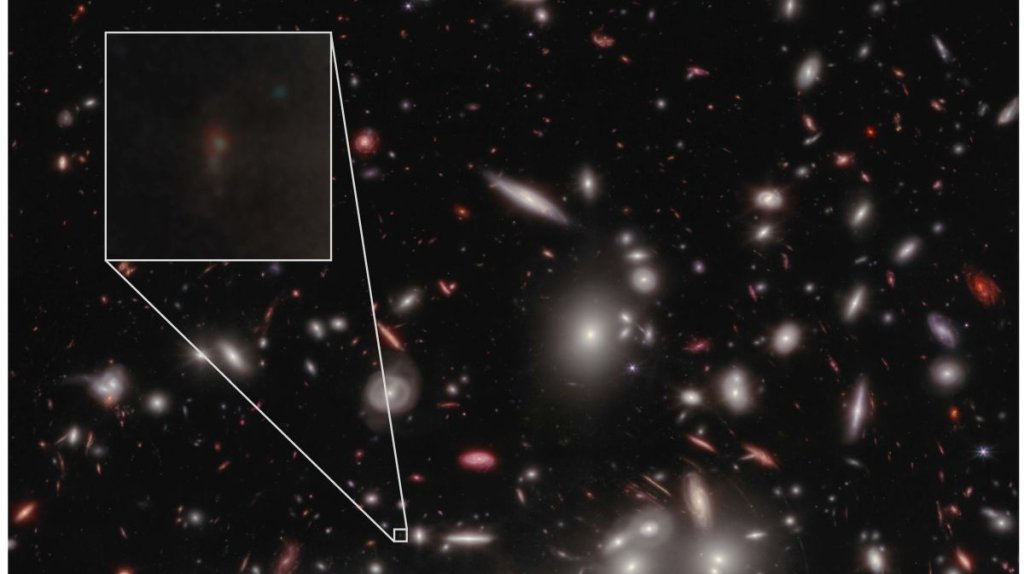

There’s still no clear verdict on the winner of that contest, but JWST helped astronomers crown a different champion last month. They just confirmed the faintest galaxy yet seen in the early universe, a result published in the journal Nature.

“Before the Webb telescope switched on, just a year ago, we could not even dream of confirming such a faint galaxy,” UCLA astronomer Tommaso Treu, a co-author on the new work, said in a press release.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — A complete guide

This galaxy, known as JD1, is part of the first generation of galaxies to pop up in our universe‘s 13.8-billion-year history. It’s about 13.3 billion light-years away from us, meaning we’re observing it as it looked when the universe was only a few hundred million years old — a meager 4% of its current age. This early era of the universe is known as the “epoch of reionization,” the time when the first stars formed and ushered the universe out of darkness.

Astronomers are still trying to figure out exactly what the first galaxies looked like, and how they were able to light up the universe to create what we see today. Most of the infant galaxies JWST has spotted are bright, but they’re thought to be outliers. Instead, astronomers suspect that fainter, smaller galaxies like JD1 did most of the heavy lifting during reionization.

“Ultra-faint galaxies such as JD1, on the other hand, are far more numerous, which is why we believe they are more representative of the galaxies that conducted the reionization process,” said study lead author Guido Roberts-Borsani, an astronomer at UCLA, in the same press release.

JWST’s powerful infrared instruments were only part of the reason astronomers were able to observe JD1. They also used a technique called gravitational lensing, in which light from a distant object is bent by the gravity of something huge in the foreground, like a cluster of galaxies. This acts like a magnifying glass, making faraway objects appear bigger and brighter — and, in the case of JD1, possible to spot.

“The combination of JWST and the magnifying power of gravitational lensing is a revolution,” said Treu. “We are rewriting the book on how galaxies formed and evolved in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang.”

Editor’s note: The author works at the same university as the researchers behind the new findings, but was not involved in this project.