James Webb Space Telescope finds ‘puffball’ exoplanet is uniquely lopsided (Image Credit: Space.com)

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have discovered that a “puffy” planet is asymmetric, meaning there is a significant difference between one side of the atmosphere and the other.

The extrasolar planet or “exoplanet” in question is WASP-107 b, which orbits an orange star smaller than the sun located around 210 light-years away. Discovered in 2017, WASP-107 b is 94% the size of Jupiter but only has 10% of the mass of the solar system gas giant. This means it is one of the least dense exoplanets ever discovered, far “puffier” than expected.

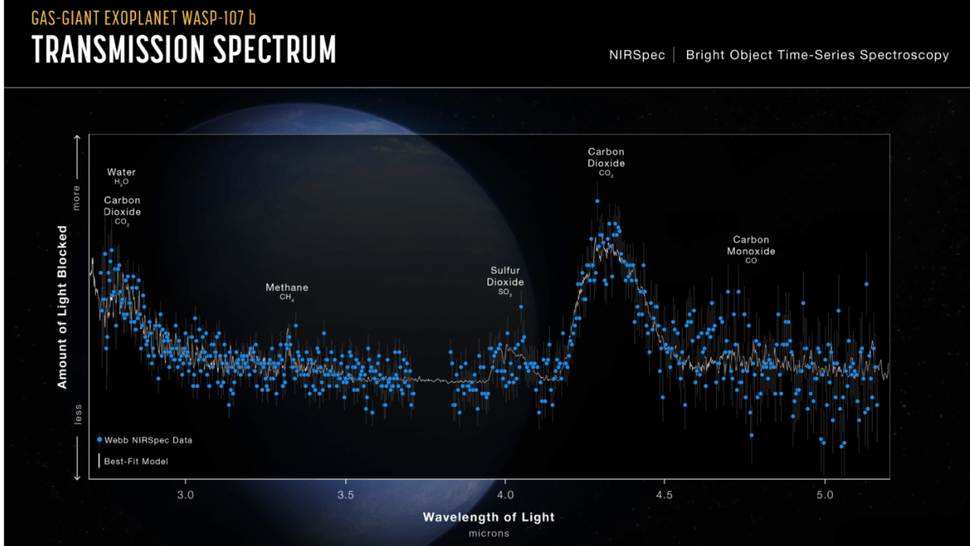

Earlier this year, scientists determined this is likely the result of the interior of WASP-107 b being much hotter than predicted, and the planet is also thought to possess a rocky core that is larger than what was previously modeled. These strange characteristics were explained by a scarcity of methane in its atmosphere. Now, scientists have another WASP-107 b mystery to solve.

The curious asymmetry of WASP-107 b presents astronomers with a conundrum. “This is the first time the east-west asymmetry of any exoplanet has ever been observed from space as it transits its star,” Matthew Murphy, a graduate student at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory, said in a statement.

Murphy and colleagues studied WASP-107 by recording light from its host star as it passed through the atmosphere of the planet as it crossed or “transited” the face of its star. “A transit is when a planet passes in front of its star — like the moon does during a solar eclipse,” Murphy said, adding that “observations made from space have a lot of different advantages versus observations that are made from the ground.”

Related: Exoplanets may be hiding behind the ‘Neptunian ridge’

WASP-107 b is unbalanced

WASP-107 b orbits its star at a distance of around 5 million miles, or about 6% of the distance between Earth and the sun. This means that the planet completes an orbit in around five Earth days. In addition, the exoplanet is tidally locked to its star. This results in one side, the “dayside,” permanently facing the star, while the other, the “nightside,” faces out to space in perpetuity.

The exoplanet isn’t as hot as many worlds so close to their stars. Its temperature is 890 degrees Fahrenheit (477 degrees Celsius), which puts it between the hottest exoplanets and the relatively chilly planets of the solar system. WASP-107 b is uniquely light in terms of density, which gives rise to weak gravity and results in a highly inflated atmosphere.

“We don’t have anything like it in our own solar system. It is unique, even among the exoplanet population,” Murphy said.

Because elements absorb and emit light at characteristic wavelengths, the spectrum of light passing through an atmosphere can reveal what that atmosphere is made of via a technique called transmission spectroscopy. Because the JWST was able to observe WASP-107 b as it passed in front of its star, scientists were able to determine the composition of its atmosphere.

The JWST’s high precision also allowed the team to get “snapshots” of the exoplanet and separate signals emerging from its east and west sides. This allowed them to better understand the processes happening in the atmosphere of WASP-107 b.

“These snapshots tell us a lot about the gases in the exoplanet’s atmosphere, the clouds, the structure of the atmosphere, the chemistry, and how everything changes when receiving different amounts of sunlight,” Murphy continued. “Traditionally, our observing techniques don’t work as well for these intermediate planets, so there’s been a lot of exciting open questions that we can finally start to answer.

“For example, some of our models told us that a planet like WASP-107b shouldn’t have this asymmetry at all — so we’re already learning something new.”

The team now plans to examine the data they collected with the JWST more closely to build a better picture of WASP-107 b and pinpoint what is causing the asymmetry in its atmosphere.

“For almost all exoplanets, we can’t even look at them directly, let alone be able to know what’s going on one side versus the other,” Murphy concluded. “For the first time, we’re able to take a much more localized view of what’s going on in an exoplanet’s atmosphere.”

The team’s research was published on Tuesday (Sept. 24) in the journal Nature Astronomy.