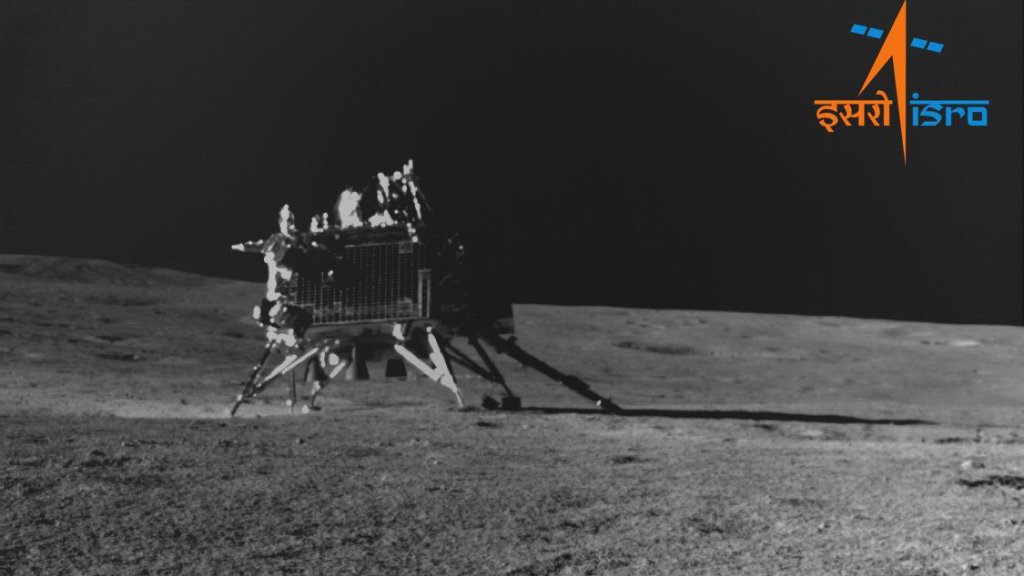

India’s Chandrayaan-3 moon rover Pragyan snaps 1st photo of its lander near the lunar south pole (Image Credit: Space.com)

India’s Pragyan moon rover photographed its mothership, the Vikram lander, for the first time, as the two continue their ground-breaking exploration halfway through the Chandrayaan-3 mission.

The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) released two black and white images of Vikram on Wednesday, Aug. 30, showing the Chandrayaan-3 mission’s lander propped up on its legs against the dust-covered lunar surface.

“Smile, please📸! Pragyan Rover clicked an image of Vikram Lander this morning,” ISRO said in a post sharing the images on X, formerly Twitter. “The ‘image of the mission’ was taken by the Navigation Camera onboard the Rover (NavCam).”

According to the post, the image was taken on Wednesday (Aug. 30) at 7:35 a.m. Indian Standard Time (10:30 p.m. EDT on Tuesday, Aug. 29, or 0130 GMT on Wednesday). One of the images is annotated, showing two of Vikram’s science sensors deployed on the moon’s surface — the Chandra’s Surface Thermophysical Experiment (ChaSTE) and the Instrument for Lunar Seismic Activity (ILSA).

Related: Why Chandrayaan-3 landed near the moon’s south pole — and why everyone else wants to get there too

The Chandrayaan-3 mission landed on the moon on Wednesday, Aug. 23. One day later, the Pragyan rover descended from the lander, and both spacecraft began their scientific explorations. In the week since the landing, the mission has sent home a series of images and videos of Pragyan roaming around on the lunar surface, leaving tracks in the lunar soil. The image released today is the first showing the lander through the rover’s eyes.

The mission’s ChaSTE payload made headlines earlier this week when it took temperature measurements of the lunar surface, the first such measurements taken near the southern polar area by a sensor placed directly on the surface rather than from orbit. The instrument has a probe, which drilled 4 inches (10 centimeters) deep into the soft lunar regolith to understand how temperature of the soil changes with depth.

The measurements revealed an incredibly steep thermal gradient in the surface layer: Just 3 inches (8 cm) below the surface, the soil is a freezing 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 10 degrees Celsius), while the surface is boiling at over 140 degrees F (60 degrees C).

The moon‘s surface can get incredibly hot during the two-week lunar day because the body, unlike Earth, is not protected by a thick atmosphere that would absorb the sun’s heat and balance out the differences between the times when sun rays reach the moon’s surface and when they don’t.

The temperatures measured by Vikram are still rather mild. Previous measurements by spacecraft orbiting the moon showed that, especially around the moon’s equator, temperatures can reach a hellish 260 degrees Fahrenheit (127 degrees Celsius) during the day and plummet to frigid minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (-173 degrees Celsius) at night, according to NASA. For this reason, crewed missions to the moon have to take place during the lunar dawn when the moon warms up just enough for humans to be able to work but before it gets too hot.

In a separate announcement, ISRO said that Chandrayaan-3 found traces of sulfur in the lunar soil. Sulfur has previously been found in small quantities in samples brought to Earth by the 1970s Apollo missions, but scientists were unsure how common this mineral is on the moon. Scientists think that lunar sulfur comes from past tectonic activity and therefore learning more about its abundance could help them better understand the moon’s past.

Chandrayaan-3 is now half-way through its planned lifetime as neither the rover nor the lander are expected to survive the upcoming two-week lunar night. The solar-powered vehicles’ batteries are not powerful enough to keep their systems going when temperatures plummet and darkness covers the lunar surface.

The mission is India’s first successful attempt to land on the moon and the world’s first successful landing in the southern polar region. Previously, only the U.S., the former Soviet Union and China have managed to place their spacecraft on the lunar surface with a controlled descent. Earlier this year, a Japanese lander called Hakuto-R crashed when it hit a crater rim during its descent. Russia’s Luna-25 mission met a similar fate just three days before Chandrayaan-3’s success. India itself previously attempted a lunar landing with Chandrayaan-2 in 2019; although the Chandrayaan-2 lander crashed due to a software glitch, its orbiter still studies the moon from above.

The southern polar region that Chandrayaan-3 studies is of immense scientific interest as its permanently shadowed craters are believed to hold substantial amounts of frozen water. This water, scientists believe, could be extracted and used to make drinking water and oxygen for future human crews, which would bring down the cost of such missions.

Astronomers are also eyeing the dark craters in the region. As temperatures inside these craters are very stable, scientists think they could provide an ideal environment for next-generation space telescopes that would enable researchers to peer deeper into the universe than is currently possible.