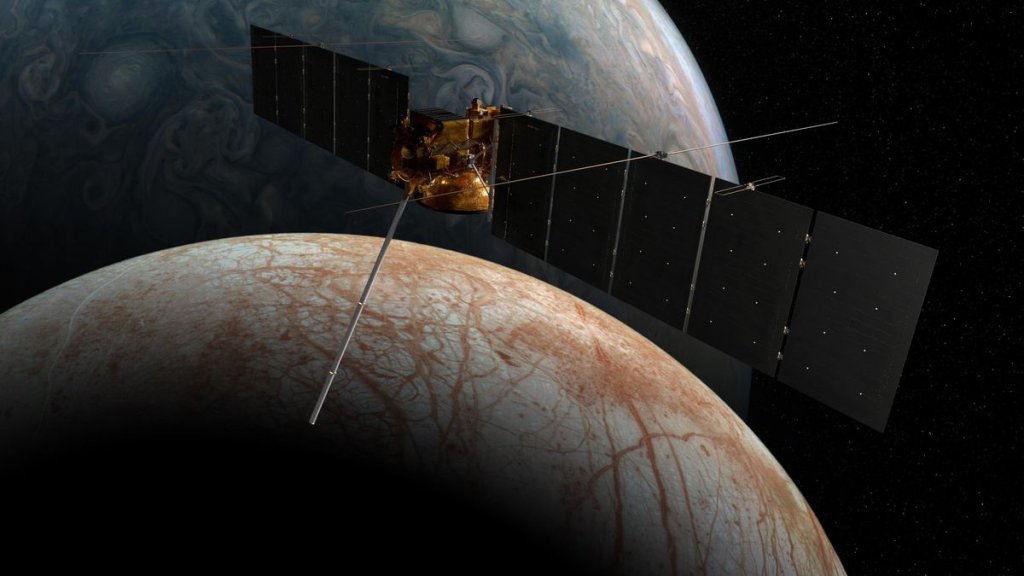

I’m sending my name to Jupiter’s moon Europa on a NASA spacecraft — and here’s why you should, too (Image Credit: Space.com)

In 2024, if all goes to plan, a spacecraft named the Europa Clipper will embark on a journey to an icy, gray moon of Jupiter covered in rust-colored gashes. It will swim along the Jovian satellite’s gravitational tides, half facing the orb from orbit, half exposed to the airless ocean of space. And alongside its high-tech spectrometer, radar system, optical imager and other instruments built to search for proof of alien habitats, the Europa Clipper will be bringing my name. It can bring yours, too.

You just have to sign up for NASA’s free “Message in a Bottle program” here. The campaign closes at 11:59 p.m. EST on Dec. 31 (0459 GMT on Jan. 1); at the time I’m writing this, almost 900,000 names have been entered.

If you’re unsure why this matters, however, you’re not alone. Right after signing my name, and honestly before I even knew what that would entail, I thought pretty deeply about why I want this to happen. After all, the spacecraft won’t be landing anywhere. There’s no one on Europa to receive our message. Each name is one among hundreds of thousands of others. Even our names are simply intangible concepts created to denote our existence, an idea that linguists and philosophers have plunged into for years. Without us, what are our names? Without anyone to read them, where have they truly gone?

This sent me into a spiral. It felt like I was taking part in a highly abstract concept.

I eventually decided that the point of this might not be to yield any physical consequences, or even any notable theoretical consequences for that matter. I think I sent my name to Europa because that’s where it’s not supposed to be. I’m tethered to Earth, so if my name is meaningless without my existence, perhaps it should stay here too. Yet, thanks to modern technology, it doesn’t have to.

Even if my name doesn’t have a concrete presence in reality, and should therefore be able to “travel” across light-years and perhaps transcend dimensions, I am not sure it can “be” somewhere unless there’s someone in that place to think of it. And there’s no one on Europa (I suppose, to the best of our knowledge) to think of it. Or to think of yours. So maybe NASA is offering us the next best thing, allowing our names to take residence somewhere besides the neighborhood of Earth, the only neighborhood in which they’ve been thought of.

So after sorting through all this, and telling my family members I signed them up as well (to which my father expectedly responded with a thumbs up emoji and the word “ok”) I figured out how, exactly, Message in a Bottle works.

In a nutshell, scientists with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory designed a special “silicon wafer” that looks something like a super shiny, metallic disk. They are then able to turn small images like, say, a bubble letter “A” into very tiny, readable text. Those small images are called “bitmaps.” Each name entered into the project will undergo this process, eventually becoming text on the scale of 75 nanometers, or a thousandth the width of a human hair. All the names can then be “stenciled” on silicon microchips, built from the original wafers, via an electron beam.

All those chips can then be loaded onto the Europa Clipper, which will hopefully travel over a billion miles while catapulting itself through the forces of other planets until it reaches the gravitational embrace of Europa. The spacecraft will then make nearly 50 flybys of the moon at closest-approach altitudes only 16 miles (25 kilometers) above the surface. Meanwhile, it’ll dutifully be searching for proof of subsurface oceans and perhaps even evidence of biosignatures.

So, to take a line from one of my favorite paragraphs in the novel “Red Mars,” microchips engraved with words that represent almost 1 million humans will sit in a location from which the Earth appears as only a star.

Ultimately, this whole exercise may not change anything except my perspective, but I think that’s enough.