Humans are pumping out so much groundwater that it’s changing Earth’s tilt (Image Credit: Space.com)

Earth’s tilt has changed by 31.5 inches (80 centimeters) between 1993 and 2010 because of the amount of groundwater humans have pumped from the planet’s interior.

In that period, humans removed 2,150 gigatons of water from natural reservoirs in the planet’s crust. If such an amount was poured into the global ocean, its surface would rise by 0.24 inches (6 millimeters). A new study has now revealed that displacing such an enormous amount of water has had an effect on the axis around which the planet spins.

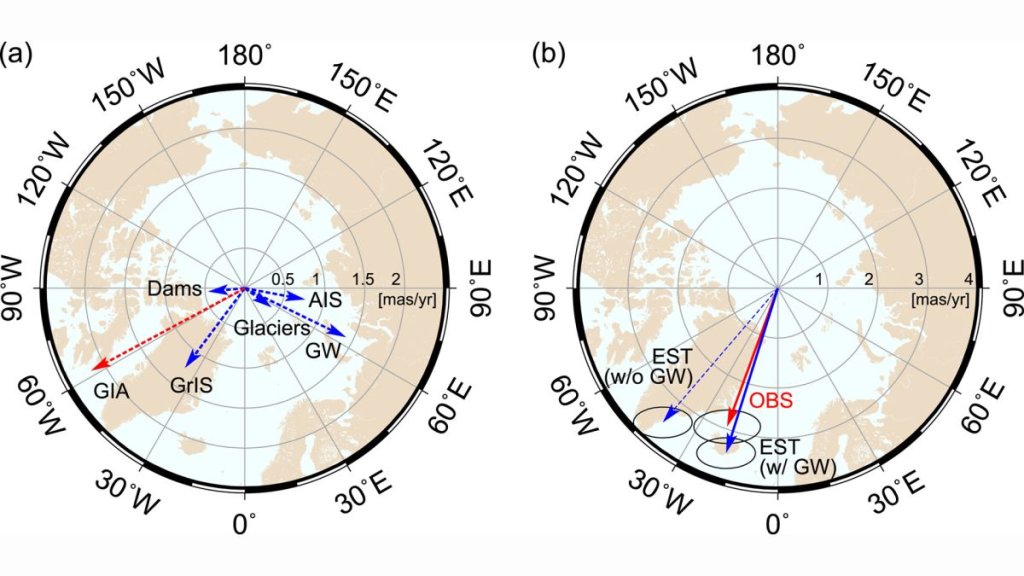

Scientists arrived at this conclusion by modeling the changes in the position of Earth‘s rotational pole, the point at which the planet’s imaginary axis would stick out of the surface if it were a physical object. The position of the rotational pole is not identical with the geographical north and south poles and actually changes over time, so the rotational axis cuts through different spots on the planet’s crust at various points in time.

Related: Climate change has altered the Earth’s tilt

Since 2016, scientists have known that the rotational pole is affected by climate-related processes, such as the thawing of icebergs and the redistribution of the mass of the water locked in them. But until the researchers added the pumped-out water into their models, the results hadn’t perfectly matched observations. Without the pumped-out groundwater, the model was off by 31 inches (78.5 centimeters).

“Earth’s rotational pole actually changes a lot,” Ki-Weon Seo, a geophysicist at Seoul National University who led the study, said in a statement. “Our study shows that among climate-related causes, the redistribution of groundwater actually has the largest impact on the drift of the rotational pole.”

Since the tilt of Earth’s axis can have an effect on seasonal weather on the planet’s surface, scientists now wonder whether the shifts of the rotational pole could contribute to climate change in the long-term.

“Observing changes in Earth’s rotational pole is useful for understanding continent-scale water storage variations,” Seo said. “Polar motion data are available from as early as the late 19th century. So, we can potentially use those data to understand continental water storage variations during the last 100 years. Were there any hydrological regime changes resulting from the warming climate? Polar motion could hold the answer.”

Overall, the Earth’s rotational pole shifts by several meters a year. How much drained groundwater reservoirs contribute to this shift depends on where on the planet they are located. The study showed that water removed from mid-latitudes has the largest effect on the planet’s tilt.

Managing how groundwater moves around the globe could therefore help limit the shifts of the rotational pole and thus the potential climate effects that come with them.