How countries can increase their participation in the global space economy (Image Credit: Space News)

The question we’re most often asked by government and industry executives in our overseas travels is “How do we increase our participation in space activities?” With over 100 countries already engaged in space, there is increasing interest in developing unique national strategies to seize opportunity and scale businesses in the space economy.

Space activities are global, and the ecosystem is growing fast on a march to a $1 trillion economy. For the world to access its greatest potential in space, there are common factors that every nation will need to address. While we often think about space activities as vast and distant, in this context, just like politics, space is local.

According to the latest data from The Space Report, the global space economy is worth $570 billion. Interest in space capabilities and access is growing, and thoughtful engagement demands consideration of the many legal, industrial, workforce, infrastructure and international activities related to space. What’s needed is a focus on developing a national space ecosystem that enables a real basis for success. Because each country holds a unique mix of industrial and technological maturity, academic focus, natural resources, talent and public needs, each will inevitably take a different path developing its space ecosystem. Additionally, political realities and a country’s overall business climate have important effects, as does the national culture in which innovation has been fostered and allowed to mature.

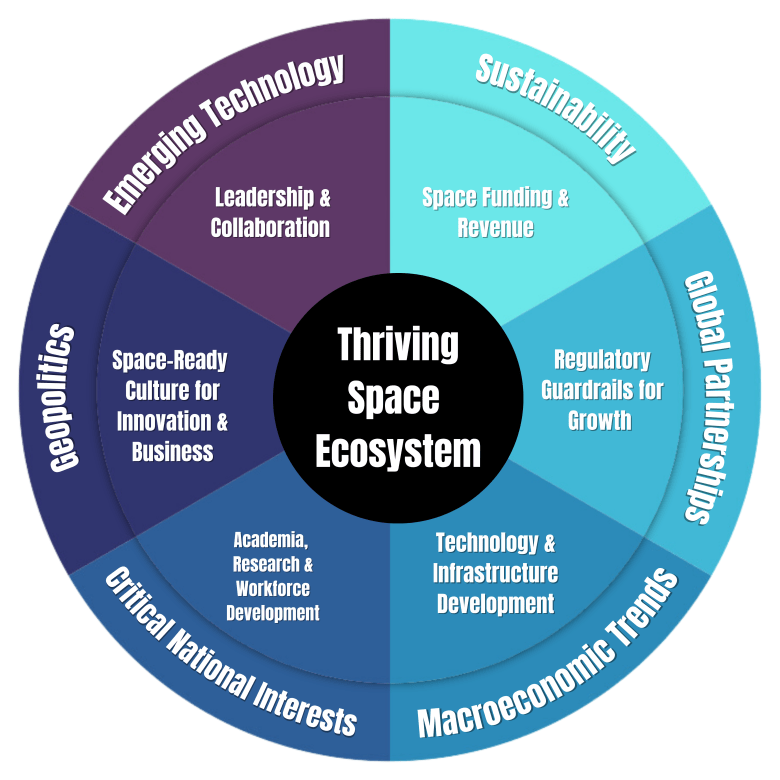

We have identified six broad components of a thriving space ecosystem. Assembling these components into a coherent framework will help leaders and policymakers identify areas for improvement, targeted investment and public sector action. While there is not a universal recipe for success, we believe that each of these factors need some focus and attention in a manner that works best for each nation. Leaders should ask themselves: which of these components are already mature, which need to be developed, which could be improved and what actions and decisions could grow out of this understanding?

Six space ecosystem components

1: Leadership and collaboration

The complexity of space activity requires national policy makers, parliamentarians, regulators and administrators to align ambitions, goals, programs and capabilities with national directives. Because space impacts so many aspects of our daily lives, national strategy demands the attention of presidents or prime ministers, and requires thoughtful development. This should involve space, science and defense agencies, as well as other departments with a stake in the space community, such as finance, diplomacy and transportation.

Many countries already have space experience; their leaders and lawmakers may reshape government bodies to oversee space activity, or even create new agencies. They should seek to craft a space mandate that informs public policy, strategy and funding mechanisms to foster space activity. The United States’ National Space Council is one example of how to integrate diverse public and private interests over routine intervals, and prioritize action.

National laws and regulations should be agile and transparent, subjected to regular review and adapted as new space capabilities and activities rapidly emerge. At the same time, compliance with the Outer Space Treaty and other international agreements signal a commitment to responsible and cooperative behaviors in the pursuit of space activities. Countries should also look abroad for technology or capacity-building partnerships that will ultimately enhance their own space activities.

2: Space funding and revenue

Economics matters. While recent technology and modern business models have lowered barriers to entry, space activity is still characterized by high upfront costs with time-to-return on investment (ROI) measured in years and sometimes decades. Government missions typically measure ROI in non-economic terms, such as new scientific understanding or enhanced security, and ROI across different space market segments varies depending on space technology, industrial maturity and stakeholders.

Startups and entrepreneurs need funding to innovate and scale. Government funding is generally suited to high-risk, long-term endeavors (such as deep-space exploration or novel technology applications) while private investment is appropriate for fueling business growth in an existing or emerging market segment (such as downstream satellite data processing). That said, we are finally seeing the return of venture funding to higher risk space initiatives. To support these latter examples, a spectrum of capital sources must be available, including venture capital, private equity and bank lending. Preparing the investment community for space requires engagement from public sector leaders who can help investors examine opportunities, understand the risk profile associated with technology development in different space market verticals, and navigate the policies and regulations that could alter the speed and direction of business.

Governments can support revenue growth by creating credible demand signals, connecting private sector offerings to government demand and facilitating efficient evaluation and acquisition processes. Governments should ultimately strive to be an initial customer (but not the only customer) and be clear about their commitment timelines for a specific space capability.

Customer base diversification is critical to scaling space companies, and governments are often best positioned to buy first and validate a product or service, which can inspire confidence from other interested parties. Additionally, governments should explore public-private partnerships to help fund the innovation cycle — from demonstration to scale — to ensure that capital is available at every stage of development.

3: Regulatory guardrails for growth

A growing space ecosystem requires domestic regulations tailored to modern space challenges and opportunities. The modern-day space industry grew out of the Apollo era, during which space activities were overwhelmingly focused on government priorities and directed from the top down. Not only has the space industry grown over the past six decades, so have the ways we build spacecraft and pursue space activities. Some 90% of all spacecraft put into orbit in 2023 were commercial, whereas 93% of all spacecraft launched up until the 1990s was done so by the Soviet Union and the U.S. Space technologies and activities have evolved, and so too must a nation’s regulatory environment.

Whether creating new rules or amending those in effect, the regulatory regimes surrounding space activity need to permit (rather than restrict) speed and flexibility, and must create a business climate conducive to start-ups and enterprise growth. Past U.S. policies have mandated the streamlining of regulations on commercial use of space or emphasized high-priority areas like positioning, navigation, and timing resilience or cybersecurity of space systems. Regulations must be developed jointly with industry to ensure their relevance and effectiveness in a global space market. Industry stakeholders and the local start-up community should be engaged from the beginning to discuss the barriers to entry, current technical focus areas and future capabilities. It helps everyone understand and prepare for the coming landscape and also helps public sector leaders strategically design space regulations based on market realities, rather than top-down.

Additionally, since space is a global domain, government leaders should consider how international regulatory regimes (and specifically, the Outer Space Treaty) impact their space activities and growth goals. For example, space safety and sustainability need to be incorporated into every aspect — government, commercial and international — of national space strategy.

4: Technology and infrastructure development

Space activity is technology and infrastructure intensive. Far more than just rocket launches and satellites, space access requires coordinated supply chains, communications and data infrastructures and cutting-edge innovation. Significant advances in space technology have been accelerated by the convergence of other emerging technologies that have applications in the space domain. Nations seeking to increase participation in space should leverage the strengths and maturity of in-country adjacent industries, whether traditional ones like defense and mining or newer ones such as artificial intelligence, robotics, cloud computing, data science and analytics and high-precision manufacturing. These industries are already working with technologies that have valuable space applications. To encourage collaboration, industry leaders must be educated in current and future space opportunities and understand how their idea, product, or service enhances the space value chain. Demand from these other industrial sectors will begin to drive new innovations in the space economy.

Further, few countries have the wherewithal to develop space infrastructure across multiple verticals, like launch, remote sensing, communications, lunar exploration and others. Decisions must be made about which segments should remain fully indigenous and which can be explored via international cooperation. Industrial competitiveness should be an important consideration whereas protectionist approaches will ultimately slow progress.

5: Academia, research and workforce development

Space ecosystems thrive on talent, and growth demands steady pipelines of human capital. Reaching the space economy’s full potential will depend on a range of technical and non-technical talent. Space begins in the classroom, and we need future generations to reach for opportunities in space and see themselves as part of the ecosystem.

Focus must be placed on enhancing and expanding STEM learning and on educating the business and investment communities about space opportunities. The future is dependent on the involvement of people with a range of backgrounds, skillsets and interests — and nations should match training and education curricula to the space workforce needs of the future. This means investing in STEM learning and engagement while developing transferable soft skills (such as critical thinking and communication) for students at all levels, as well as focusing on business and financial literacy. Engagement in space is not just technical, and the ability to identify, interpret and act on market opportunity is just as valuable as the ability to develop space capabilities.

Meanwhile, private sector stakeholders need to deepen our understanding of the business of space and where capabilities and technologies fit into the ecosystem. Space business models are still uncertain, leaving business leaders and academics with the work of clarifying and improving them. Industry can develop private education and training programs to fuel their future workforce. As a part of this, governments and industries need to prioritize technology transfer and research commercialization out of universities — uniting talent pipelines, research and entrepreneurial opportunity, which together fuel private sector competitiveness and growth.

6. Space-ready culture for innovation and business

Advancing in space means leaving behind the status quo. To access the greatest potential opportunities and bring about rewards that benefit all, spacefaring nations need to nurture a daring research, business and investment community with a high-risk tolerance. A significant challenge is encouraging a culture of entrepreneurship that not only champions new businesses and start-ups but also accepts that many entrepreneurial ventures fail. Countries should focus on instilling national pride and confidence in solving hard problems in novel ways — and pivoting when the business case or innovation necessitates it. While pushing the envelope, countries and entrepreneurs need to adapt ecosystem investments and decisions to capitalize on their unique local culture and space legacy. This can include leveraging existing space infrastructure (such as ground-based telescopes, satellite arrays and military facilities) to promote research, learning, commerce and exploration.

Impact on the path ahead

These six components of a thriving space ecosystem are all necessary, but perhaps not equally straightforward to achieve. Strategy, rulemaking, investments and entrepreneurship that underpin successful space programs are shaped by external forces that impact decisions and frameworks: geopolitics, macroeconomic trends, changing critical national interests, global partnerships, the need for sustainability and the convergence of emerging and maturing technologies. The future is hard to predict and change is inevitable, but it can be monitored and adjusted, which is why a dynamic space ecosystem must be agile — from laws and regulations, to capital sources, to pivoting a startup in the face of new capabilities and market opportunities.

There is another factor, however, that will determine the long-term public appetite for space activity. People want to see real-world Earthly benefits from space programs and investment. Space activities need to make sense in a domestic context, and their impacts need to be tangible. While the public may not always fully appreciate the extent to which they rely on space every day, enhancing communication and education about how space activities and investment impacts them can narrow the knowledge gap and help increase support for national objectives.

Kevin M. O’Connell has worked on space commercialization for over three decades. He is the former Director of the Office of Space Commerce at the U.S. Department of Commerce and today runs Space Economy Rising, an international advisory firm on strategy, finance, and regulation for space companies.

Kelli Kedis Ogborn is the Vice President of Space Commerce & Entrepreneurship at Space Foundation, where she drives organizational and product growth in disruptive technology commercialization of space and defense innovations.