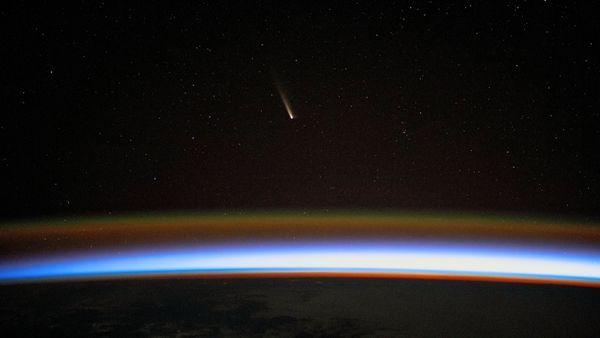

Hopes dim for another bright October comet after Tsuchinshan-ATLAS (Image Credit: Space.com)

While skywatchers around the world have been raving about the performance of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, there has been talk on social media of yet another spectacular comet due to make its appearance at the end of this month.

The lineage of this second object apparently connects it with a family of comets, some of which have been among the most brilliant ever observed. For this reason, some might have already branded it as “The Great Halloween Comet.”

Unfortunately, it now appears likely that this will not happen.

We’ll get into the specifics in a moment, but first let’s explain why there was an immediate surge of excitement when the discovery of this new comet was announced.

Discovered on Sept. 27 in Hawaii by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) project, the object was initially cataloged as “A11bP7I.” But shortly thereafter, enough observations came in to confirm that this very faint 15th-magnitude object — nearly 4,000 times dimmer than the faintest star that can be perceived without optical aid — was indeed a comet and not an asteroid. And once its existence was confirmed and an orbit for it was derived, that’s when the excitement began.

Related: The dazzling Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is emerging in the night sky: How to see it

For the newfound object, which we’ll call Comet ATLAS, is a Kreutz sungrazer.

The sungrazing family of comets

In 1888, astronomer Heinrich Kreutz (1854-1907) noted that sungrazing comets all follow approximately the same orbit. Apparently, they are all fragments of a single giant comet that broke apart in the distant past. And it’s quite probable that these fragments have themselves broken up repeatedly as they’ve orbited the sun, resulting in periods ranging from about 500 to 800 years. In honor of his work, this special group of comets are named the Kreutz Sungrazers. Two of these sungrazers (in 1843 and 1882) not only developed very long tails but also achieved the rare distinction of being bright enough to be seen in broad daylight with the unaided eye.

That helps explain the excitement around Comet ATLAS. When the comet broke onto the scene last month, social media interest in viewing it increased almost exponentially overnight. Orbital calculations showed that it was destined to indeed “graze” the sun on Oct. 28, coming within a mere 341,000 miles (548,000 kilometers) of our star.

Ikeya-Seki 2.0?

Back in October 1965, another Kreutz sungrazer, Comet Ikeya-Seki, became so brilliant that at its peak it reportedly was 10 times brighter than the full moon and was visible even in the daytime, merely by blocking the sun with a hand or behind a building.

In the days following its sweep around the sun, Ikeya-Seki was a spectacular sight in the late October and early November morning skies. An incredibly brilliant, twisted tail stretched up from the east-southeast horizon an hour or two before sunrise, appearing like a slender searchlight beam about as long as the Big Dipper.

At its maximum length, Ikeya-Seki’s tail extended for 70 million miles, ranking it as the fourth-largest ever recorded. Only the Great Comets of 1680, 1811 and 1843 had tails stretching farther out into space. While Ikeya-Seki’s head faded rapidly, the tail continued to be visible well into November even as the comet moved rapidly away from the sun.

Since the newfound Comet ATLAS was moving in a similar orbit and would be also moving around the sun just a week later in the calendar compared to Ikeya-Seki’s 1965 performance, many arbitrarily assumed that we’re in for another spectacular comet show this year at the end of October into November.

But sungrazing comets are far from rare.

Most ‘grazers are tiny, but Comet ATLAS is (relatively) big

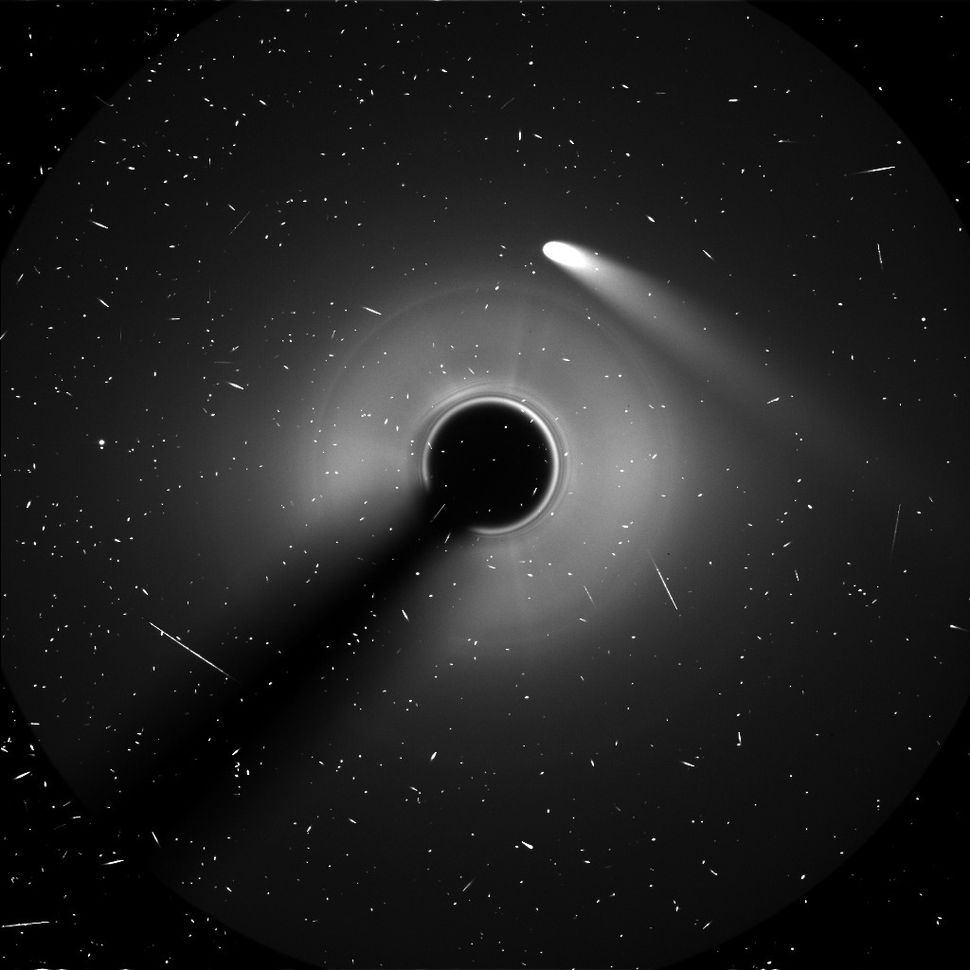

Beginning in 1979, orbiting space observatories began to detect sungrazing comets using instruments called coronagraphs. A coronagraph is designed to look at the solar atmosphere by blocking out the bright disk of the sun. Tiny sungrazing comets, which normally would be too faint and too near to the glare of the sun for us to see, can be picked up using a coronagraph.

In fact, sungrazers are now routinely being discovered using the Large Angle Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) satellite, a joint effort of the European Space Agency and NASA. Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS (which is not a sungrazer) passed within the field of view of LASCO coronagraph for a few days centered on Oct. 9.

Amateur astronomers have discovered thousands of comets using SOHO imagery on the internet, and SOHO comet hunters come from all over the world. More than 5,000 SOHO comets have been identified as Kreutz sungrazers. Some are probably just a few meters across; none have survived their sweep around the sun.

Comet ATLAS, however, appeared to be much larger, perhaps a mile or two (2 or 3 km) across, causing some to speculate that it could become very bright. For instance, Japanese comet expert Seiichi Yoshhida has suggested that it might reach magnitude -4.5 — as bright as the planet Venus.

But, sadly, these forecasts now appear to be overly optimistic.

Low expectations for a good show

Based on the latest observations from the Comet Observation Database (COBS), Comet ATLAS has been excruciatingly slow to brighten as it approaches the sun. The latest estimates place it at a magnitude of only 12 or 13 — still very faint. Some observers have even suggested that it has dimmed slightly in recent days, and that its nucleus has even split into two pieces. That break-up was apparently confirmed on Oct. 9, by The Astronomer’s Telegram.

Perhaps the most damning statement about the future of Comet ATLAS was recently posted on the International Comet Quarterly Facebook page by John E. Bortle, a renowned amateur astronomer who has made a special study of comets, having observed more than 300 in his lifetime.

He writes:

“This latest Kreutz family comet has no real chance of surviving. Around 30 years ago, I did an analysis of the photometric behavior of all the then known Kreutz group members seen from 1843 until the 1980s. In that study, I determined that the great Comet of 1965 (Ikeya-Seki) was actually the intrinsically faintest member of the surviving Kreutz group family in the past 150 years. Those only a bit fainter than this essentially do not survive their closest approach to the sun (perihelion) intact at all. Such was the case with the Great Comet of 1887 and the more recent Comet Lovejoy of 2011, surviving only as tail remnants as far as ground observers were concerned. Most even fainter members simply fade out completely within hours of their closest passage to the sun.”

“Given that Comet ATLAS seems to be several magnitudes fainter compared to Comet Ikeya-Seki,” concluded Bortle, “I firmly anticipate that, even under the best of circumstances, this newcomer can only hope to present itself as a short-lived disembodied tail post-perihelion, if any sort of remnant at all.”

Shades of the Great Pumpkin

As previously noted, some social media sites have suggested that Comet ATLAS could get “super-bright” by Halloween. But unfortunately, based on the evidence that we at Space.com have presented here, that does not look to be the case. Indeed, there now appears to be a good chance that, when Comet ATLAS arrives at its closest point to the sun on Oct. 28, the tremendous heat and tidal forces of our star will cause its nucleus to completely fragment, disintegrate or simply dissolve, perhaps leaving in its wake (as Bortle suggests) nothing more than a disembodied tail.

In a way, it harkens back to the story told annually in the “Peanuts” comic strip about The Great Pumpkin. In that story, Linus believes that, on Halloween night, The Great Pumpkin will rise out the pumpkin patch, delivering toys to those who believe in him. Of course, The Great Pumpkin never appears, leaving Linus greatly disappointed.

So, it would appear that those who believe they will get a view before sunrise of a “Great Halloween Comet” in 2024 will, like Linus, almost certainly be disappointed.

Anticipation . . .

But just when will another large and spectacular member of the Kreutz group, like Ikeya-Seki, appear? No one can say for sure. The last Kreutz Sungrazer to become bright was Comet Lovejoy in 2011. It’s not possible to estimate the chances of another very bright Kreutz comet arriving in the near future. But given that at least a dozen have reached naked-eye visibility over the last 200 years, another great comet from the Kreutz family will almost certainly arrive at some point.

Indeed, these comets are like trains of all sizes moving along the same railroad track while passing our station (Earth) in space.

And, like an impatient commuter, we can only watch and wonder what awaits us up the track!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.