Here’s how to see ‘horned’ comet 12P/Pons-Brooks in the night sky this month (video) (Image Credit: Space.com)

You might get a chance to catch sight of a comet this month.

All you’ll need to see comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, besides fair weather and a little luck are good binoculars or a telescope and sky map to help guide you to where this celestial vagabond happens to be. The comet bears the names of two of the most renowned comet hunters of all time.

First, let’s talk about how it was discovered, then, how much we know about it from an historical standpoint and then finally, when and where you should look for it.

Related: Comets: Everything you need to know about the ‘dirty snowballs’ of space

The discoverers

Jean-Louis Pons (1761-1831) was a French astronomer, who went on to become the greatest visual comet discoverer of all time. In today’s world, comets are routinely found when they are far out in space, beyond the ability of being picked up by human eyes, but are caught using robotic cameras attached to large telescopes either here on Earth or from satellites out in space.

In contrast, Pons made most of his discoveries using telescopes and lenses of his own design; his “Grand Chercheur” (“Great Seeker”) was an instrument with a large aperture and short focal length, similar to telescopes that our modern-day amateurs would refer to as a “comet seeker.” Pons is noted today for visually discovering 37 comets (still a record) from 1801 to 1827.

One of those discoveries came on July 12, 1812. When first sighted, Pons described it as “a shapeless object with no apparent tail,” but over the next month, the comet became bright enough to be dimly visible to the naked eye. On Aug. 15 that year, it reached its peak brightness at fourth magnitude (Magnitude indicates an object’s degree of brightness. The lower the figure of magnitude, the brighter the object.) The new comet also possessed a split tail measuring approximately three degrees.

Orbital calculations suggested that comet Pons was periodic, taking somewhere between 65 and 75 years to circle the sun.

On Sept. 2, 1883, British-born American comet observer William R. Brooks (1844-1921) accidently found it. Like Pons, Brooks was a prolific discoverer of comets. In fact, his total of 27 visual discoveries is second only to Pons. Not until the first orbital calculations of Brooks’ discovery was made, was it realized that this comet and the comet found by Pons of 1812 were one of the same. So, this comet now bears the surnames of both observers.

With an orbital period of roughly 71 years, comet Pons-Brooks is considered to be a “Halley-type” comet, that is, a comet with an orbital period between 20 and 200 years, often appearing only once or twice within one’s lifetime. Other comets with a similar orbital period include 13P/Olbers, 23P/Brosen-Metcalf and the most famous of all, 1P/Halley. Because it was the twelfth comet to have a definitive orbital period calculated, it is cataloged today as 12P/Pons-Brooks.

Past performances

That 1883-1884 apparition of 12P/Pons-Brooks was quite favorable because it made its closest approach to Earth of 58.6 million miles (94.3 million km) on Jan. 10, 1884, just 16 days before it passed closest to the sun (perihelion) at a distance of 72.5 million miles (116.7 million km). During this time frame the comet reached third magnitude and in binoculars displayed a tail measuring some 20-degrees in length.

It also seems that whenever this comet arrives at perihelion in late fall or early winter, is when it puts on its best displays. In 2020, German astronomer, Maik Meyer demonstrated that the appearance of a naked-eye comet mentioned by the Chinese in November 1385, and another that was observed by an Italian astronomer in January 1457 were probably relatively bright apparitions of 12P/Pons-Brooks. And there is some evidence that an ancient record of a bright comet dating back to 245 A.D. might also have been 12P.

Also, of special interest in 1883-1884 was that, on a few occasions, this comet seemingly was prone to sudden outbursts or flare-ups in brightness, helping to brand it as a famously capricious comet.

In fact, en route toward its next return to the vicinity of the sun in May 1954, 12P/Pons-Brooks experienced four more unexpected outbursts. But at its closest to the Earth that year, the comet was more than 2.5 times farther away compared to 1884 and so it was not as bright or as impressive, peaking at magnitude +6.4 (near the threshold of naked-eye visibility) and producing a tail that measured only a half-degree in length.

Flare supply

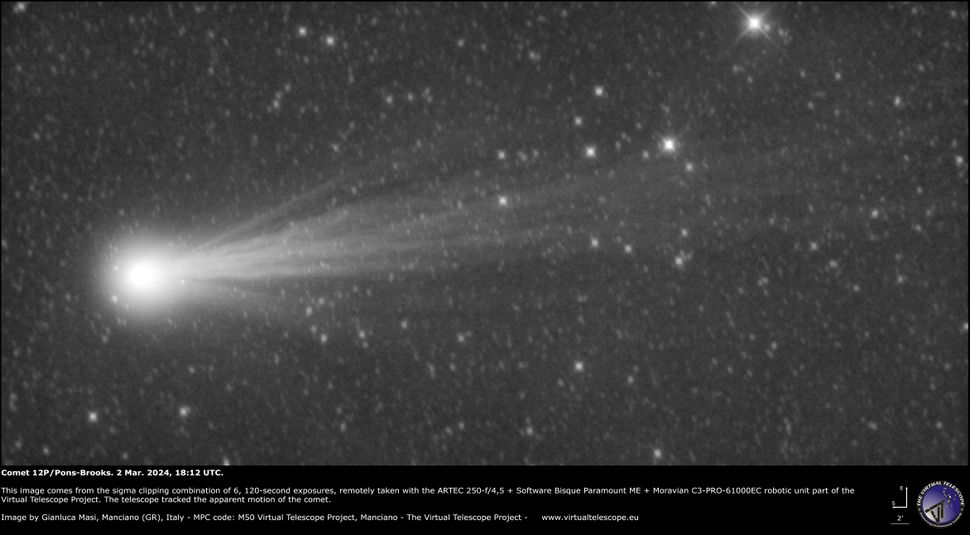

This year, 12P/Pons-Brooks will arrive at perihelion on April 21, but it is already up to its old tricks regarding sudden flare-ups in brightness. Last July 20, an unexpected brightness outburst caused it to briefly become about 100 times brighter and, the shell of expanding gas surrounding its nucleus (called the coma) expanded to resemble, for some, a horseshoe.

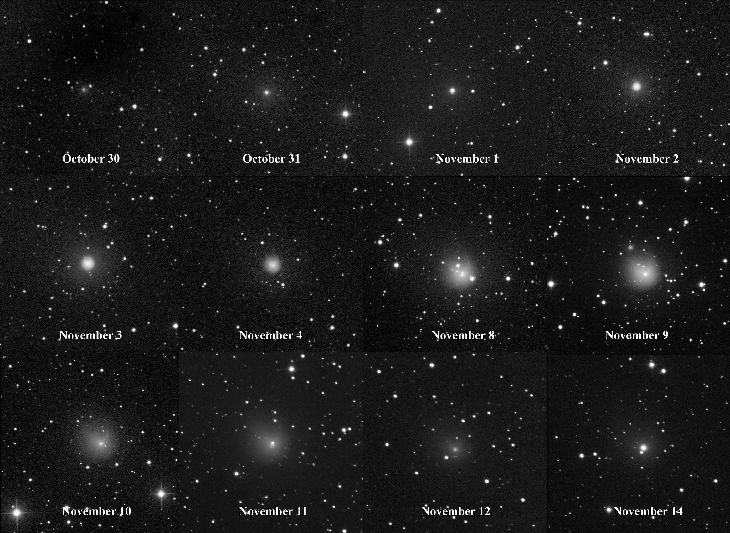

Others, however, suggested a horseshoe crab, the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars, the cartoon character Yosemite Sam, or even — as many news media outlets christened it — the horns of a devil, a.k.a. “The Devil’s Comet.” Other outbursts occurred on Oct. 5, Nov. 1 and 14, Dec. 14 and most recently on Jan. 18.

And additional flares seem possible as we move through this month.

The exact cause of these flares is unknown, although Richard Miles of the British Astronomical Association thinks 12P may be one of 10 to 20 known comets with active ice volcanoes. The “magma” is a cold mixture of liquid hydrocarbons and dissolved gasses, all trapped beneath a surface which has the consistency of wax. These bottled-up volatiles can explode when sunlight opens a fissure.

For this reason, some have dubbed 12P as a “cryovolcanic comet.”

Tracking the comet

From now, through the end of March, 12P/Pons-Brooks will be visible in the early evening sky, within the constellation of Andromeda the Princess, to the upper left of the Great Square of Pegasus and hovering about 20-degrees above the west-northwest horizon at the end of evening twilight.

With the aid of a good sky chart and a dark sky, it should be readily accessible in binoculars. Its apparent night-to-night motion will now be accelerating as it draws nearer to the sun. By mid-month, it will have shifted into Pisces, the Fishes; now perhaps a 6th-magnitude object, it should be a fine sight for binoculars.

And by the end of March, it may brighten to 5th-magnitude, reaching naked-eye visibility against the backdrop of the zodiacal constellation of Aries. By now, a short tail may also have formed.

Thereafter, the comet will disappear into sunset glow during April and will arrive at perihelion on April 21 at a distance of 72.6 million miles (116.8 million km). 12P/Pons-Brooks passes 22-degrees northeast of the sun in mid-April, but then will fade very rapidly and largely become an object for Southern Hemisphere observers. It will have probably dropped to 6th or 7th magnitude by the end of May and 8th or 9th magnitude by the end of June.

Future flares and the solar eclipse

There has been some talk that should 12P/Pons-Brooks undergo another flare-up in the coming weeks that it might become a very bright, even spectacular object. Unfortunately, that does not appear to be likely. Space.com asked the well-known comet expert, John Bortle for an assessment of how the comet may “perform” in the days ahead.

His belief is that while 12P/Pons-Brooks brightened dramatically last summer when the comet was far from the sun and just beginning to get active, that for any flare-ups in the near-future, the comet will not appear to brighten very much because the overall brightness of the comet has increased significantly as it now has moved much closer to the sun.

“As a result,” notes Bortle, “the outburst brightness cannot overwhelm the overall brightness of the comet’s coma as easily.”

So, any additional flares or outbursts will probably result in only a minor surge in the comet’s brightness.

There has also been talk that 12P might be visible during the total solar eclipse on April 8. “But,” adds Bortle, “I would think that much more a fantasy than anything else.” Indeed, the comet is not expected to get much brighter than magnitude +4.5 around eclipse time; far too dim — even with a little help from a flare — to see.

Next time?

After 12P/Pons-Brooks moves back out into space, it will take another 71 years for it to complete another full circuit around the sun. For most of us, this year’s appearance will be the only time we will see it.

But the very young who are around now, perhaps might get a second opportunity in the summer of 2095. The Japanese orbital expert Hiroshi Kinoshita of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) has calculated that 12P will arrive at perihelion on August 10th of that year.

If you want to see comet 12P/Pons-Brooks or any other comet in the night sky for yourself, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you’re looking to take photos of comet 12P/Pons-Brooks or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to view and photograph comets, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.