Handle Mars with care: Guidelines needed for responsible Red Planet exploration, experts say (Image Credit: Space.com)

Astronauts who explore Mars should be careful not to leave too heavy of a footprint, experts stress.

Indeed, human exploration of the Red Planet poses risks to gathering possible evidence of life on Mars, scientists say. After all, here on Earth, comparable sites of scientific interest have suffered significant damage.

“We risk the same for Mars without legal or normative frameworks to protect such sites,” suggests a new research paper that calls for “geoconservation” principles applied to space — a term dubbed “exogeoconservation.”

Related: Life on Mars could have thrived near active volcanoes and an ancient mile-deep lake

Nascent field

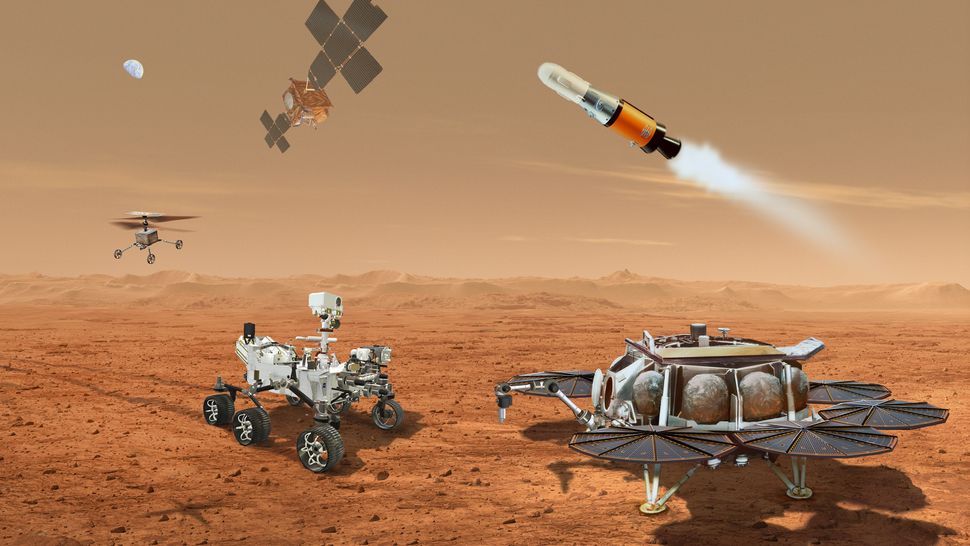

At present, exogeoconservation is a nascent field, one that is unorganized and practically ineffective. Furthermore, there is urgency to develop international agreements and accepted norms on exogeoconservation in the study of Mars, given the growth of government missions to the Red Planet, including robotic sample gathering, and as private Mars missions get underway.

Toss in future human excursions to Mars, as well as projected colonization and chatter about potentially terraforming the Red Planet, transforming it to Earth-like conditions.

This budding new phase in Mars exploration brings with it potentially devastating impacts to palaeoenvironments and geology. Current policies and laws guiding human activity in space, including Mars, are extremely limited in terms of conservation, the new study stresses.

Geoheritage value

The research paper, titled “Exogeoconservation of Mars,” and a set of recommendations are authored by Clare Fletcher of the Australian Center for Astrobiology in Sydney, along with center colleagues Carol Oliver and Martin Van Kranendonk, who is also with the School of Earth and Planetary Science at Curtin University in Perth, Australia.

The thrust of the paper, they comment, is to ensure that locales of geological significance on Mars do not suffer the same damage as many sites on Earth have faced. Sites on the Red Planet can be practically conserved while still allowing science and exploration to continue, they say.

“Geoconservation allows humanity to protect Earth’s story and geological history,” the researchers observe, “so that present and future generations can experience Earth’s aesthetic beauty, conduct scientific research, connect with various cultures, adequately protect and ensure the functioning of Earth’s biology and ecosystems, and learn about the history of our planet.”

Geoconservation, the research team points out, “does not preclude continued human activities in an area, but seeks to ensure a balance between human activities and maintaining the geoheritage value of a site.”

Impactful activities

In terms of Mars, understanding the planet’s geological, climatic and potential astrobiological history, the research group argues, “raises questions regarding the protection of key geoheritage sites that provide insight into understanding Mars’ history and the possibility of life elsewhere in the solar system.”

Existing and yet-to-be-defined key sites on Mars that are of universal geoheritage value, the researchers advise, will require “urgent protection,” given that the nature of Mars exploration is evolving to become more sample-oriented — such as those now being collected by NASA’s Perseverance rover — leading to “increasingly impactful activities” due to human sojourns to the Red Planet.

Geovandalism

Spotlighted in the paper are two case studies here on Earth involving the Komati River Gorge in South Africa and the Pilbara Early Life Sites in Australia. They exemplify significant damage to geological sites of outstanding universal geoheritage value.

“Both sites provide insight into Earth’s geological evolution and are of astrobiological significance, meaning that they are analogous to sites of astrobiological and palaeoenvironmental importance on Mars,” Fletcher and colleagues explain.

That said, the Komati River Gorge suffered from “geovandalism,” while the Pilbara Early Life Sites underwent extensive sampling soon after its discovery. It no longer contains any evidence of ancient life, and the site was deemed not worth conserving.

Special regions

Already identified on Mars by expert teams are “special regions,” places where terrestrial organisms on the Red Planet might survive and thrive.

“Conserving sites of scientific value is incredibly important, keeping in mind that conservation does not mean ‘ringfencing’; sites, but rather applying enough protection to allow continued study and ensure current and future researchers can understand a site and learn of the scientific value[s] contained at a site,” Fletcher told Inside Outer Space.

“There is no difference in exogeoconservation priority between scientific sites and special regions,” Fletcher continued, “but they require different protections, and therefore different studies to be conducted.”

On the same page?

Having the entire global space community on the same page when it comes to exogeoconservation is vital, Fletcher says, “as any one actor has the ability to forever change a site.”

This applies not only to different nation-states, but also to private organizations, consortiums, etc.

“This is where traditional legal frameworks become tricky, too, particularly as United Nations treaty ratification has decreased for every subsequent space-related treaty, and we now see the introduction of entirely new legal frameworks such as the Artemis Accords,” Fletcher pointed out.

NASA, in coordination with the U.S. Department of State, established the Artemis Accords in 2020. They were spurred by countries and private companies performing missions and operations around the moon, so a common set of principles to govern the civil exploration and use of outer space was deemed necessary.

Precautionary approach

As for Mars, “understanding what norms can be created and co-opted by the global space community provides an avenue to affect change without issues associated with changing legal frameworks and attaining signatures and/or ratification of such frameworks,” Fletcher added.

Fletcher noted that follow-on work is centered on more practical measures for exogeoconservation, such as what studies need to be undertaken to determine what scientific sites get conserved — and in what way.

“A precautionary approach, international cooperation, in both legal regimes and norms, interdisciplinary work, and understanding the mistakes and successes that have occurred on Earth,” the research paper concludes, “will ensure that exogeoconservation on Mars protects important sites without compromising continued exploration and scientific studies.”