Good Mars weather lets NASA’s power-starved InSight lander live a little longer (Image Credit: Space.com)

Martian weather has given a lander extra time to catch marsquakes.

NASA’s InSight lander touched down on Mars in November 2018 with tools meant to help scientists see deep into the Red Planet. InSight runs on sunlight and dust has covered its solar panels, leaving the lander able to generate just a tenth of the power it could harvest as a Martian newcomer. Scientists expected that the lander would run out of power by the end of the summer, but InSight is still eking out science data and may continue to do so for several months to come — potentially even into January.

“However, if we get a dust storm or anything like that, then it can be sooner,” Chuck Scott, project manager for InSight at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, which manages the mission, told Space.com. “We’ve gotten down so low now that if we get any kind of Mars weather, that could spell the end of the mission.”

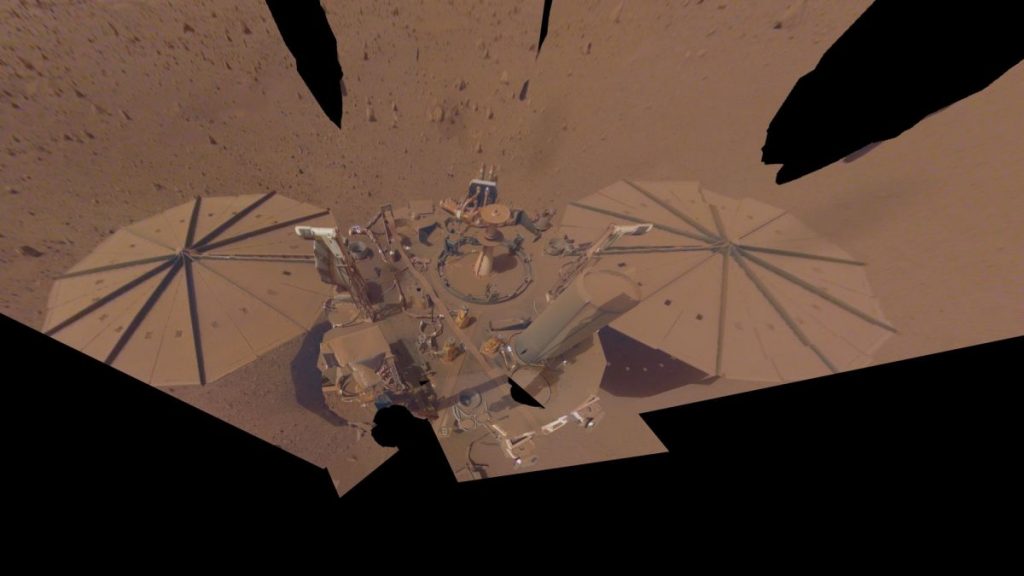

Related: NASA’s Mars InSight lander snaps dusty ‘final selfie’ as power dwindles

How much power InSight can produce each Martian day, or sol, depends on two factors: the dust piled on its solar panels and the dust in the Martian atmosphere. During a dust storm, both factors can cause trouble.

Plenty of Martian explorers have faced the same problem: Although the Perseverance and Curiosity rovers use nuclear power, their predecessors the twin Spirit and Opportunity rovers both battled dust buildup, and a dust storm ended the Opportunity mission.

But Spirit and Opportunity found unexpected aid from “cleaning events,” likely bursts of wind — from, ironically, dust storms — that removed dust and boosted their power production. InSight hasn’t had that kind of luck, and attempts to shake the dust off and to mimic a cleaning event by drizzling dust near the panels didn’t do much.

So as early as June 2021, InSight personnel estimated that the lander would be forced to shut down this spring. By May, they thought the spacecraft could continue through the end of the summer and implemented a mode meant to prioritize getting power to the seismometer. The team also reset InSight’s rules to avoid the protective “safe mode” that spacecraft usually enter when something is wrong — it will work right up until it doesn’t.

But the lander is still working. “Since then, we have changed our operations a little bit and we have also had a bit of Mars weather that’s lucky for us, because we haven’t been having any big dust storms or anything,” Scott said.

Now, InSight is entering a season during which scientists usually see some regional dust storms, which they thought would speed the lander’s demise. But the season is beginning more gently than it has in the past, offering InSight a reprieve.

“We were kind of expecting that there would be some regional dust storms and that would cause a problem for us,” Scott said. “But in looking at the weather this year, the people that forecast that Mars weather, they are believing that we’re not going to see any regional storms still for another couple of weeks.”

When InSight landed, it could generate 5,000 watt-hours each sol (which is about 40 minutes longer than an Earth day). Ever since, the power has decreased. “Every time there’s a storm or something on Mars, it’ll go down,” Scott said. Some storms knocked 100 watt-hours off production, some more like 1,000, he added. “It’ll vary depending on how large the storm is.”

The spacecraft is currently producing about 400 watt-hours each sol, putting it at less than one tenth the capacity it had at landing. The lander needs to make about 300 watt-hours each sol to keep the seismometer, communications and basic functions running, Scott said.

Some day, when the lander hasn’t hit that, it will put itself into what mission personnel call “dead bus,” when the spacecraft silently runs out the last of its battery. “It’ll get to a point where the battery will fail and there’ll be no way for it to reboot itself,” Scott said.

Mission personnel aren’t sure exactly how long the final battery drain will last, but it could potentially take a couple of years. And there is a small chance that a friendly gust of wind during that period could clear enough dust for the solar panels to get back to work.

“Based on what we’ve seen, we think the likelihood of that during the period of time before the battery actually fails is maybe 10%,” Scott said. “So once we go into dead bus, that’s pretty much going to be the end of the mission.”

But even with “dead bus” looming, the team is working to get every piece of data from InSight it can. Mission scientists have determined that the lander can go down to eight-hour observing sessions and still yield useful data. For now, the lander is using about half the day to recharge and half the day to run its seismometer. As power supplies dwindle, that balance will shift until the lander observes for eight hours at a time then takes a couple of sols to recharge between sessions.

“We are still getting quakes; we can still see things occuring in the seismometer,” Scott said, noting that the lander caught a marsquake at the end of August.

“We expect that to continue all the way down until the mission ends,” he said. “We’re just trying really hard to get as much science as we can out of the vehicle, all the way down to the very end till it actually dies.”

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.