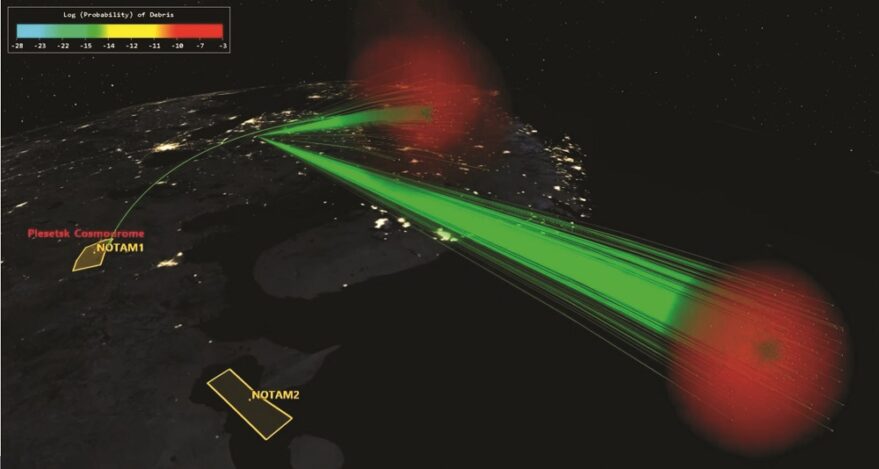

Some operators of low Earth orbit satellites are bracing for a storm of debris. Russia’s demonstration of an antisatellite weapon last November, destroying the Cosmos 1408 satellite, created thousands of tracked pieces of debris, and many more too small to be tracked.

Much of that debris remains in orbits similar to the satellite, with an inclination of 82.3 degrees. That means the debris can end up running headlong into satellites operating in sun-synchronous orbits at inclinations of 97 degrees.

“When they sync up, you have the perfect storm: they’re in the same orbit plane but counter-rotating, crossing each other twice an orbit, again and again,” said Dan Oltrogge, director of integrated operations and research at COMSPOC. They create surges of close approaches, or conjunctions, dubbed “squalls” by the company, that can last for several days before the orbits drift apart.

The worst of the conjunction squalls is forecast for the first week of April, when the ASAT debris encounters several groups of Dove imaging cubesats operated by Planet as well as satellites operated by Satellogic, Spire and Swarm. The number of conjunctions will approach 50,000 per day during that time, compared to a background level of about 15,000 per day. Fortunately, because many of those satellites are cubesats, the risk of collisions won’t rise as dramatically.

What’s notable about this analysis, beyond the existence of the squalls themselves, is that it was done by a private company, COMSPOC, and not by the Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron or the Office of Space Commerce. Oltrogge said COMSPOC has met with Planet and others, including NASA and the Space Force, about its assessment.

The COMSPOC analysis is part of a trend of growing private sector capabilities to track objects and warn of potential conjunctions. LeoLabs operates a network of radars to track objects in LEO, while ExoAnalytics and Numerica operate telescopes to keep tabs on satellites in geostationary orbit. NorthStar Earth and Space is planning a satellite constellation to track satellites from orbit. Startups like Kayhan Space and Neuraspace use various data sources to provide more accurate assessments of potential collisions.

A WAZE APP FOR SPACE

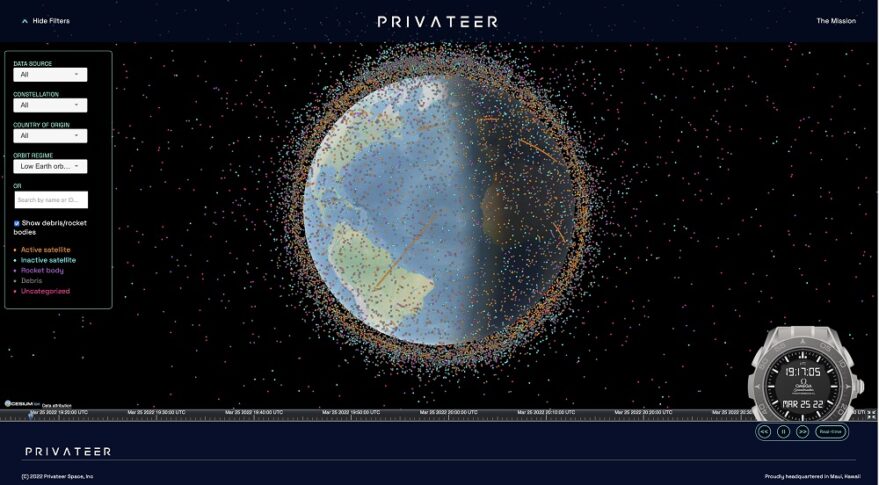

The newest entrant into the commercial space traffic management industry is Privateer. The company, based in Maui, Hawaii, had kept a low profile but attracted interest in large part because of one of its founders: Apple co-founder Steve “Woz” Wozniak.

Privateer emerged from stealth on March 1 with its first product: a visualization tool called Wayfinder that combined data from several sources, including data from U.S. Space Command and provided directly by satellite operators.

Wayfinder is based on ASTRIAGraph, developed by Moriba Jah, a University of Texas at Austin professor who is also chief scientist of Privateer. “It’s a rearchitecting of ASTRIAGraph,” he said in an interview. “ASTRIAGraph is always going to exist, but this is going to be a branch off of that.”

He described Wayfinder as a demonstration of other space traffic management capabilities that Privateer can provide. “Wayfinder will be this platform, a kind of Waze app, that people can build different services on top of,” he said. One example would be adding information about the characteristics of objects, in addition to their orbits, which would be valuable for companies planning satellite servicing or debris removal services.

One of those new products is a collision warning service that Alex Fielding, chief executive of Privateer, calls Relssek, or “Kessler” spelled backwards: a play on the Kessler Syndrome of runaway growth of orbital debris. That will combine catalogs with data from satellite operators themselves or other sources to provide more accurate predictions of conjuctions. “We’ll use anybody’s assets that are already there,” he said.

That includes potentially its own satellites. Privateer is working on a three-unit cubesat called Pono-1 that will launch later this year with 42 sensors to collect space situational awareness data. Fielding said the company was considering flying more sensors as hosted payloads on other companies’ satellites rather than their own. “We really don’t want to create more stuff in space.”

GOVERNMENT PARTNERSHIPS WITH INDUSTRY ON STM

While companies speed ahead, the development of government solutions is moving slowly. NOAA, which hosts the Office of Space Commerce, provided the first public demonstration in February of the open architecture data repository (OADR) it is developing to host space situational awareness data. But, officials said it won’t be ready to enter service, and take over the civil space traffic responsibilities assigned to the Commerce Department in Space Policy Directive 3 in 2018, until 2024.

That mismatch between the public and private sectors is prompting calls to reconsider their respective roles. That includes, some argue, a greater role for companies to shape both space traffic management and the development of norms and rules for safe operating in increasingly congested orbits.

“I’m really worried that we’re not doing enough, we’re not moving fast enough here,” said Kevin O’Connell, former director of the Office of Space Commerce. “How are we going to stay agile and adaptive? It’s largely through the efforts of the private sector.”

O’Connell, speaking at the FAA Commercial Space Transportation Conference in February, said he supports Space Policy Directive 3, the 2018 policy that assigned civil space traffic management responsibilities to the Commerce Department, which hosts the office he once led, but that the scale of the problem means that the office needs to work more closely with those private-sector capabilities.

“It’s not the government versus the private sector. That’s a silly way to think about it,” he said. “Where we need speed and innovation, we need to leverage the private sector.”

How that cooperation would work in practice, though, is still a work in progress. SPD-3 envisioned that the Commerce Department would cooperate with both commercial and international partners on its civil STM system, incorporating their space situational awareness data into the OADR to improve the accuracy of conjunction predictions.

NOAA issued a request for information (RFI) in February, seeking details about commercial data that could be incorporated into the OADR. That request included an emphasis on data from assets in the southern hemisphere and the capability to track “high-priority objects” on short notice.

That RFI is the start of NOAA’s efforts to engage with the private sector in space traffic management. Stephen Volz, NOAA assistant administrator for satellite and information services, said at the FAA conference there will be workshops and other meetings with companies. “You can see where we’re going and where we can learn and improve,” he said.

SPD-3 envisioned that Commerce would provide a basic level of space traffic management services free of charge. Companies would then be able to provide more advanced services using data from the OADR and other sources.

Volz confirmed that he expected the Office of Space Commerce to provide “a basic set” of such services. “We do not see that as the role of NOAA or the DoC to provide everything to everyone, but to provide a certain minimum and growing capability standard that everyone can rely on.”

What the difference is between basic and advanced, though, is not clear. O’Connell warned it may be difficult to quantify that, which can affect the business plans of companies planning to offer such services. It’s in the interest of global leadership of the United States to make some space safety data freely available to all, he said, but “we don’t want to get in the way of companies that want to go above and beyond that.”

“THE CLOCK IS TICKING”

The same interactions between the public and private sectors apply to regulatory issues. The Federal Communications Commission is examining how to best evaluate the collision risk of new satellite constellations, including evaluating the aggregate risk of those systems to the overall orbital environment, rather than looking at the risks of individual systems.

“One of the things that we’re advocating for is an understanding of what are limits to sustainability, quantitatively, on a global basis, because it’s a globally shared resource,” said Mark Dankberg, executive chairman of Viasat, who backs the FCC effort.

But who does that quantitative assessment? “I think that, in the U.S., a government organization should be able to do that. So far, none have stepped forward,” he said.

One approach would be for the FCC to work with private or nonprofit organizations with expertise in space sustainability, such as The Aerospace Corporation. Another option is the Space Sustainability Rating, a scale modeled on the LEED rating system for buildings to measure how well satellite systems follow best practices for space sustainability. A consortium organized by the World Economic Forum developed the rating system, which is being administered by Swiss university EPFL.

“One of the things you might imagine is that a government licensing authority would want a rating. They may collect a fee from an applicant and then hand that fee to someone like EPFL and ask them to provide a rating,” Dankberg said. That would get around companies paying EPFL directly for sustainability ratings, which pose conflicts of interest concerns.

There’s no lack of expertise in the FCC to tackle this issue, he argued. “I think what is lacking is the will to deal with it,” he said, particularly among FCC leadership. “I think that it opened a can of worms that is not as palatable on the eighth floor as it is in the satellite bureau.”

Meanwhile, low Earth orbit is getting more crowded and dangerous, as the recent conjunction squalls identified by COMSPOC showed, even as companies plan new constellations, commercial space stations and other emerging space applications.

“Lots of people think that improving conjunction analysis is the endgame. No, it’s the starting game for a whole new set of services in terms of space safety to enable all of these exciting things,” said O’Connell, referring to those new markets. “We’re going to have to pick up the pace on the many different things we’re doing, and leveraging the private sector is a critical tool for being able to do that. The clock is ticking.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of SpaceNews magazine.