Full Worm Moon brings 1st lunar eclipse of 2024 next week. Here’s how to see it (Image Credit: Space.com)

During the next two weeks, there will be two eclipses on the astronomical docket. The main event, of course, will be the Great North American Eclipse on April 8 that will stretch from the Pacific coast of Mexico, on to Texas and across southern and eastern portions of the United States and Atlantic Canada, before coming to an end over the north Atlantic Ocean.

But two weeks before the total solar eclipse, during the overnight hours of March 24-25, it will be the moon’s turn to undergo an eclipse; a prelude to grand event coming our way in early April. That final full moon before the total solar eclipse, March’s Worm Moon, will quietly slip into Earth’s outer shadow, known as the penumbra.

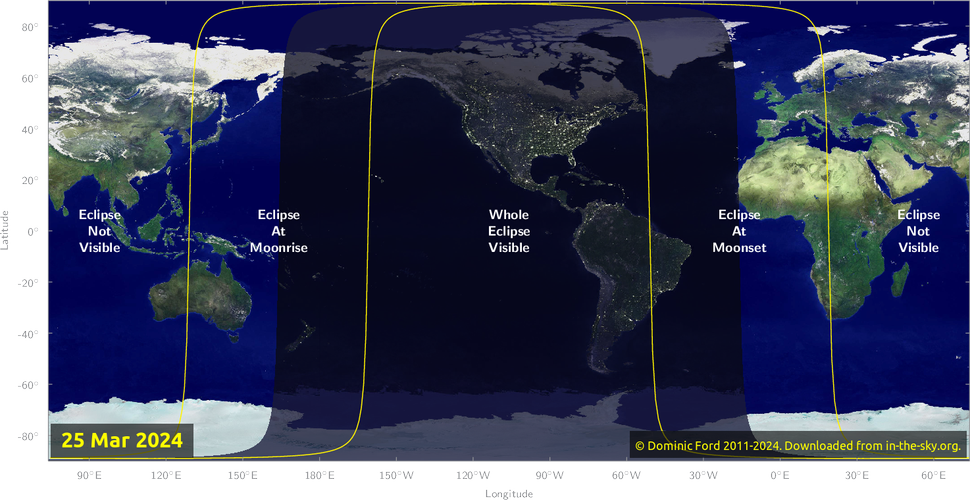

The continents of North and South America are in the best position to see this lunar eclipse, as it occurs high in their sky while the night of March 24 transitions to March 25. The moon will take 4 hours and 40 minutes to glide across the pale outer fringe (penumbra) of Earth’s shadow, never reaching the shadow’s dark umbra.

Related: March full moon 2024: The Worm Moon gets eclipsed

Read more: Lunar eclipses 2024: When, where & how to see them

Both the lunar and solar eclipses are, of course, related. A solar eclipse can occur only when the moon is at a node of its orbit. (The nodes are the two points where the moon’s path on the sky crosses the sun’s path, called the ecliptic). During the solar eclipse on April 8, the moon will cross the ecliptic from south to north. But a half orbit earlier, on March 24-25, the moon will cross the opposite node from north to south, encountering the Earth’s shadow. The timeframe when this geometry can allow for eclipses to occur is called an “eclipse season” and in this case runs from March 16 through April 23. All this is a fine example of how an eclipse season works.

In this particular case the moon is going to pass very deep into the penumbra. In fact, at the moment of the deepest phase/greatest eclipse (7:12 UT) the penumbra will reach to an extent of 95.8 percent across the lunar disk. Put another way, the lowermost limb of the moon will be 282 miles (453 km) away from the unseen edge of the Earth’s umbra.

However, penumbral eclipses are rather subtle events which are usually difficult to detect; the shadow is pale. In fact, first contact with the penumbral shadow is all but impossible to detect. But a little over an hour later, those with exceptionally acute perception might be able to detect an ever-so-slight shading of the moon’s lower left limb.

Admittedly, however, a rather underwhelming event.

The schedule

Our timetable below gives the moments for the key events of the eclipse for five time zones: Eastern, Central, Mountain, Pacific and Hawaii. All times are for the calendar date of March 25, except when accompanied by an asterisk (*), in which case the calendar date is March 24.

For the eastern U.S., maximum darkening occurs about a couple of hours before the break of dawn on March 25. Along the West Coast, it will be just past midnight, while for Alaska and Hawaii it will be during the mid-to-late evening hours of Sunday, March 24.

| Event | EDT | CDT | MDT | PDT | HST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moon Enters Penumbra | 12:53 a.m. | 11:53 p.m.* | 10:53 p.m.* | 9:53 p.m.* | 6:53 p.m.* |

| Faint smudge appears? | 2:38 a.m. | 1:38 a.m. | 12:38 a.m. | 11:38 p.m.* | 8:38 p.m.* |

| Maximum ‘darkest’ eclipse | 3:12 a.m. | 2:12 a.m. | 1:12 a.m. | 12:12 a.m. | 9:12 p.m.* |

| Faint smudge disappears? | 3:46 a.m. | 2:46 a.m. | 1:46 a.m. | 12:46 a.m. | 9:46 p.m.* |

| Moon Leaves Penumbra | 5:32 a.m. | 4:32 a.m. | 3:32 a.m. | 2:32 a.m. | 11:32 p.m.* |

The penumbral eclipse from the moon

It might be easier to understand why the penumbral shadow of Earth is so faint, by imagining actually being on the moon when Monday’s event takes place. An astronaut on the moon during this time will see an eclipse of the sun, but it would all depend on where on the moon our hypothetical moonwalker is located.

Near the moon’s upper limb is the region known as Mare Frigoris — the “Sea of Cold.” From here, the Earth’s silhouette will appear to take a small nick out of the top of the sun; hardly enough to cause any noticeable diminishing of light on the surrounding lunar landscape. That’s why the upper part of the full moon will appear to shine normally.

In contrast, as seen from Tycho, the famous brilliant lunar impact crater whose rays make it appear like a sunflower on the southern part of the moon, Earth will appear to cover more than nine-tenths of the sun’s diameter; consequently, the brilliant solar illumination of the surrounding lunar landscape will turn considerably more somber.

And this diminished effect of the glare and illumination of sunlight on the moon’s surface is precisely what assiduous sky watchers will be trying to detect during the deepest phase of the eclipse when concentrating their gaze toward the lower rim of the moon during the maximum phase of Monday’s early eclipse.

Coming attractions

Another lunar eclipse is scheduled for later this summer. On the evening of Sept. 17, the moon will slide through the lower part of the Earth’s shadow, with its uppermost limb giving a glancing blow to the dark umbral shadow of Earth. At greatest eclipse, 8.5-percent of the moon’s diameter will be within the umbra, giving the impression that the top of the moon is slightly dented.

Next year, on the night of March 13-14, 2025, the moon will undergo a total eclipse. For 65 minutes, the moon will become completely immersed in the Earth’s shadow; always a most interesting, and usually, colorful spectacle. Once again, the Americas will have a ringside seat, with all the action taking place high in the late winter sky; during predawn hours in the East and around midnight in the West.

Mark your calendars!

If you’re interested in taking photographs of the penumbral lunar eclipse of the Full Worm Moon, check out our helpful how to photograph the moon guide for the best lunar photography tips and tricks. We also have guides to the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography if you need to gear up for this or other celestial events.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications.