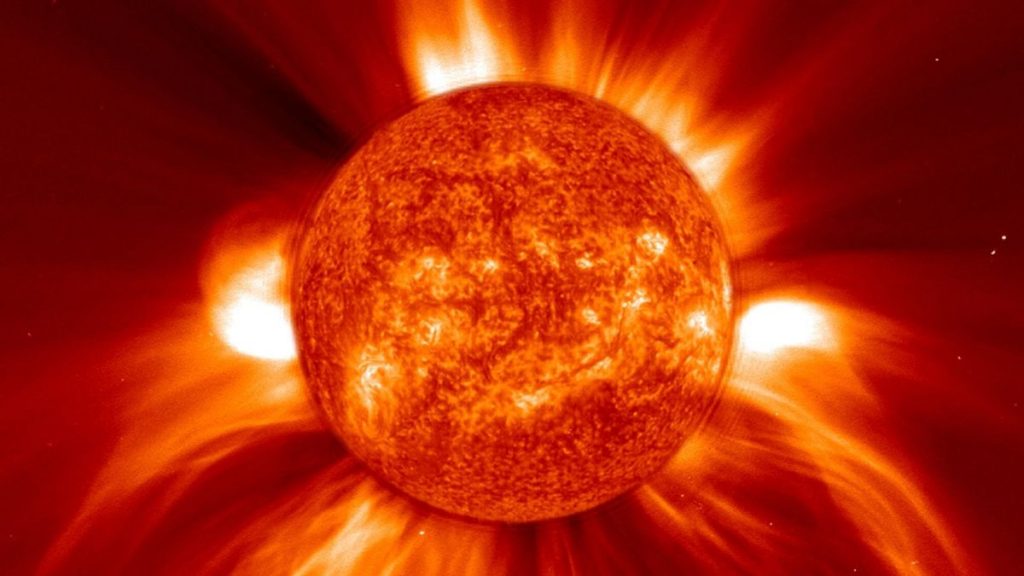

Extreme solar storms can strike out of the blue. Are we really prepared? (Image Credit: Space.com)

A surprise solar storm in 2003 disrupted hundreds of flights all over the world, caused spacecraft controllers to lose track of low Earth orbit satellites for days and cut power to tens of thousands of people in Sweden. Now, nearly 20 years later, one of the world’s leading space weather forecasters admits that our life-giving star can still catch us unprepared.

October 2003 was a quiet month at the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) of the U.S. National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA). The sleepy sun was heading toward a minimum in its 11-year cycle of activity, churning out a mediocre 100 sunspots a month. In a week, everything changed. The sun broke out with the largest cluster of sunspots in more than 10 years and pummeled Earth with a barrage of flares and plasma eruptions that unleashed the most vicious space weather event in recent history.

“I remember that October week quite distinctly,” Bill Murtagh, NOAA’s SWPC program coordinator who at that time was a space weather forecaster on duty, told Space.com. “Partly because it was my birthday, but mostly because the sun was really unremarkable. We had no idea what was going to happen just one week later.”

Related: The sun’s wrath: Worst solar storms in history

The event, which since entered history books as the Halloween solar storms, wasn’t even the worst the sun is capable of. In fact, the 2003 storms unleashed only about a tenth of the energy of the two most powerful solar storms in recorded history — the so-called Carrington Event of 1859 and the 1921 New York Railroad Storm, both of which at that time disrupted telegraph services all over the world.

Things have changed since those storms. Telegraph is a thing of the past now, but many new technologies, which we increasingly rely on, are equally vulnerable to space weather outbursts. The problem is, Murtagh says, that space weather forecasters are only marginally better at predicting those storms than they were in 2003.

“We actually identified space weather in some of our homeland security documents as one of only a couple of threats that could have a nationwide or even a global impact,” Murtagh said. “It’s kind of like the pandemic. And we’ve seen what happened with the pandemic.”

Not seeing it coming

What happened with the sun during that fateful week in 2003 when it went from quiet to mad with so little warning? It spun on its axis, the way it has done for eons, revealing a sunspot cluster 13 times the size of Earth that must have been simmering out of observers’ view for quite some time.

Sunspots are cooler regions on the sun’s surface where the star’s magnetic field is distorted so much that the magnetic lines eventually burst, releasing radiation in the form of solar flares, and plasma in the form of coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

Once that sunspot in October 2003 was aimed at Earth, a barrage of 17 solar flares and CMEs ensued, triggering widespread radio blackouts and geomagnetic storms in Earth’s atmosphere.

Related: NASA’s solar forecast is turning out to be wrong. This team’s model is still on track.

During that week, 59% of NASA’s space missions “experienced effects”, according to a NOAA report (opens in new tab). Japan’s Advanced Earth Observing Satellite 2 lost contact with ground control during the storms and never regained it. The U.S. Space Surveillance Network, which monitors objects in space, completely lost track of all satellites and space debris fragments in low Earth orbit for several days. Parts of the planet experienced radio and GPS blackouts, causing financial losses to aviation companies, which had to reroute hundreds of flights. In the Swedish city of Malmö, high-voltage power transmission lines failed; the ensuing hour-long power blackout trapping people in elevators and stopping trains in their tracks.

“Over the course of that two-week period, we had what I often call the Great Awakening,” said Murtagh, who later led a team behind the extensive NOAA report investigating the impacts of the incident. “There were so many different sectors suddenly affected and interested in our alerts.”

Do we know any better?

Fast forward nearly 20 years. The sun keeps spinning on its axis, and space weather forecasters still have very little information about what’s happening on the side facing away from Earth.

By monitoring visible sunspots, they get a rough idea of the probability of a solar flare or a CME to occur. They have, however, no way of knowing the exact time and strength of an impending outburst, and only a limited ability to predict its impact on Earth.

The mayhem of the Halloween storms was caused by solar flares and CMEs alike. Both of these phenomena originate in the sunspots when the twisted magnetic fields in those regions break and reconnect. The two often come hand in hand but arrive at Earth on different time scales.

“The solar flare is electromagnetic radiation, that is essentially light, including visible and all other wavelengths including gamma rays and radio frequencies,” Juha Pekka Luntama, the head of space weather at the European Space Agency (ESA), told Space.com. “The moment we see it, it’s already affecting Earth’s ionosphere and causing disruption.”

The radiation from solar flares “ionizes the upper atmosphere at altitudes above 80 kilometers [50 miles],” said Luntama. “It excites the atoms and molecules there and that can impact signal propagation from [GPS and GNSS] satellites. If you have a GPS or GNSS receiver, then you will see a navigation error because the characteristics of the upper atmosphere change.”

Solar flares come at different strengths, with the most powerful ones classed as X-flares. The strength of the flare is further specified by a number, with each successive digit representing a multiple of the basic strength. During the Halloween storms, the sun fired off a record-breaking X28 flare, the most powerful ever measured, which, according to NASA (opens in new tab), temporarily overloaded satellite sensors. That flare, Luntama said, threw off GPS systems in North America for several hours. According to NOAA, the positioning error of the GPS-based navigation systems used in aviation was so large that the system was completely unusable.

While the impact of the solar flare affects the day side of the globe immediately, the CMEs, which frequently arise from the sun during the same bursting of the magnetic field lines, allow space weather forecasters some time to prepare.

“The effects of the solar flare last a few hours in the worst case,” Luntama said. “The conditions return to normal, and then the CME arrives and the geomagnetic storm starts. So there is the first impact, then there is a bit of a gap. And then there is another impact. And they all come from the same solar event.”

CMEs take up to three days to reach Earth. In some cases, the orientation of their magnetic field is such that they get repelled by Earth’s magnetic shield and no geomagnetic storm ensues.

NOAA’s Deep Space Climate Observatory, or DSCOVR, about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth toward the sun, provides an advanced warning of the strength of the upcoming geomagnetic storm about an hour before the CME reaches Earth. The Halloween storms, however, produced one CME so strong that its impacts were clear almost as soon as it burst from the sun.

“That particular event that occurred on October 28 was so impressive that we understood how big the impact would be long before it reached [DSCOVR],” said Murtagh. “We were actually forecasting the most extreme geomagnetic storm [directly] from the eruption on the sun. That might have been the only time we’ve ever done that.”

Getting prepared

Despite decades of research, scientists still know very little about the activity of the sun and the intricacies of the space weather that it produces. While in many countries, severe solar storms are on the lists of hazardous events that could have nation-wide impacts, the progress to mitigate possible consequences is not as fast as it, perhaps, should be, Murtagh admits. However, he says, awareness has improved and there are policies in place to minimize the disruption.

“There’s no doubt we’re better now than we were in many areas,” Murtagh said. “For example, in the energy sector, the U.S. government requested businesses involved in electricity transmissions to do vulnerability assessments of their equipment to these geomagnetic storms and do something about it. On the other hand, there are new problems now, for example with the new satellite mega-constellations.”

An incident in February 2022 demonstrated the severity of the problems that space weather can cause for satellite operators when SpaceX lost a batch of brand new Starlink satellites after launching them into a mild geomagnetic storm. The disturbances in the upper atmosphere caused the satellites to lose altitude and fall to their demise. Other operators, too, have been reporting problems with maintaining altitudes of low-Earth-orbit satellites.

A storm of the scale of the Carrington event or even the Halloween storm would wreak havoc on satellites today, Murtagh admits, and it still could arrive with as little warning as the CMEs and solar flares in October 2003. In the future, space weather forecasting will get a little easier, as a new mission, called Vigil (opens in new tab), will be launched by the European Space Agency in 2025, finally allowing the forecasters to look “round the corner” at what is happening on the not yet visible side of the sun.

“This mission is going to be a huge development and will help us a lot not to be caught by surprise just like we were in 2003,” said Murtagh. “It will also help us to have a side view of a CME leaving the sun and coming toward Earth. It will help us improve the tracking,” and with that, the predictions of future space weather events.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.