Evidence of mysterious ‘recurring nova’ that could reappear in 2024 found in medieval manuscript from 1217 (Image Credit: Space.com)

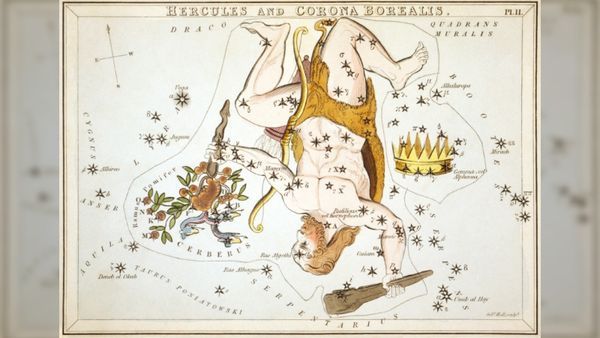

In 1217, a German monk looked to the starry southwest sky and noticed a normally faint star shining with unusual intensity. It continued to blaze for several days. Abbott Burchard, the leader of Ursberg Abbey at the time, recorded the sight in that year’s chronicle. “A wonderful sign was seen,” he wrote, adding that the mysterious object in the constellation Corona Borealis “shone with great light” for “many days.”

This medieval manuscript may have been the first record of a rare space phenomenon called a recurrent nova — a dead star siphoning matter from a larger companion, triggering repeated flares of light at regular intervals. According to new research, the “wonderful” star in question may be T CrB, which sits in the constellation Corona Borealis and dramatically increases in brightness for about a week every 80 years. But it has been scientifically documented only twice — once in 1866, and again in 1946. (The star’s next long-awaited flare-up is expected in 2024).

In a preprint paper, available on arXiv.org, astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer of Louisiana State University argues that Burchard’s record and another chronicle from 1787 constitute the first known sightings of the T CrB nova.

Related: 900-year-old Chinese supernova mystery points to strange nebula

But how can we be sure that Burchard had spotted T CrB and not some other celestial phenomenon, such as a one-off supernova or a comet? Schaefer ruled out the possibility of a supernova pretty much right away, on the grounds that if such a violent event — which occurs when a massive star dies in a dramatic explosion — had occurred that recently, it would have left behind remnants that would be clearly visible today. (The Crab Nebula, for example, is thought to be the remnant of a 1,000-year-old supernova and is visible to most telescopes today.)

Considering nobody has observed supernova remnants in the Corona Borealis star formation, it is unlikely that this kind of massive stellar explosion was the culprit. Similarly, Schaefer eliminated a bright planet from the list of suspects, as no planets visible to the naked eye wander through that region of the sky.

The possibility that the event was a comet is a bit trickier to disprove. A comet was visible in the sky earlier that year, according to a chronicle from the St. Stephani monastery in Greece. However, most monks of the time were familiar with comets, which were considered portents of doom. It’s unlikely that Burchard would have recorded a comet as something “wonderful,” or failed to mention its tail, Schaefer contends.

The 1787 sighting was recorded by English reverend and astronomer Francis Wollaston. This account describes nova-like behavior from a star whose coordinates match T CrB’s position in the sky almost exactly. While Wollaston identified this star using a name from famed astronomer William Herschel’s catalog, Schaefer believes its true identity is T CrB.

Scientists will be ready for the nova’s next expected flare in late 2024. When it comes, modern astronomers will add it to a centuries-long list of past records. In the meantime, researchers will continue digging through old archives to study T CrB’s recorded history. Hopefully, such activity will allow them to make more accurate predictions about the star’s behavior in the future.