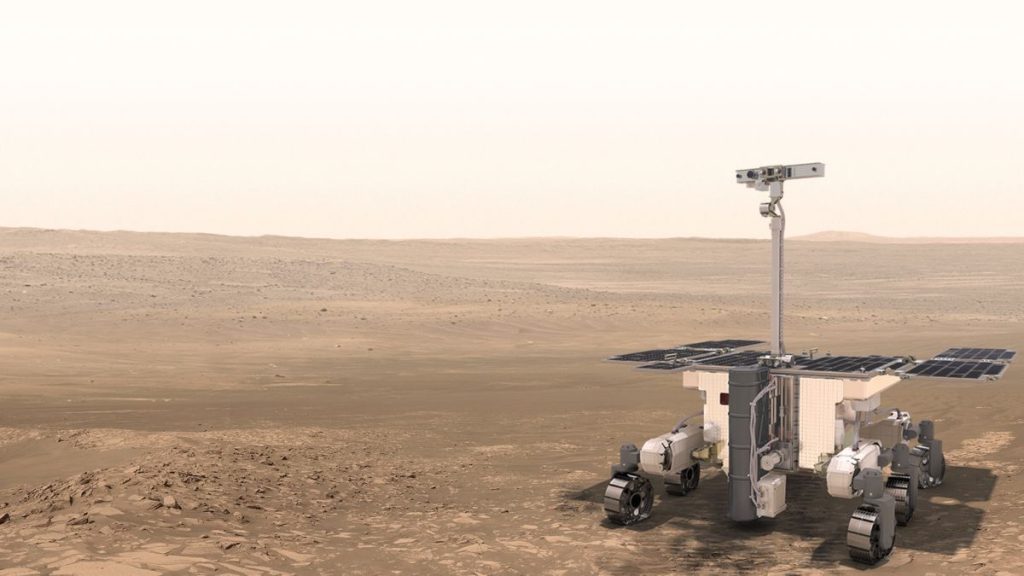

Europe’s life-hunting Mars rover unlikely to launch before 2028 due to Russia-Ukraine war (Image Credit: Space.com)

The European ExoMars rover, which was scheduled to lift off toward the Red Planet in September, is now unlikely to launch before 2028 as the European Space Agency (ESA) will have to replace its Russian-built landing platform due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Speaking at the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group meeting on Tuesday (May 3), ESA’s ExoMars project scientist Jorge Vago said the agency is currently considering its options and will soon present feasible plans to its member states.

The ExoMars project, developed in partnership with Russia, will require a significant funding boost if its rover, named Rosalind Franklin, is to make it to the Red Planet, as replacement systems for several Russian-built technologies will be needed. The rover mission, which was set to cost €1.3 billion ($1.37 billion) if launched in September 2022 with Russia, will require a new landing platform, a new rocket and several other technologies that were originally provided by Russia’s space agency Roscosmos.

“In July, we’re going to go to member states with a recommended way forward,” Vago said at the meeting. “This recommendation will have a financial forecast for how much it will cost to put the Rosalind Franklin rover on Mars.”

Related: Ukraine invasion’s impacts on space exploration

ESA officially discontinued cooperation with Russia in March after European countries rolled out sanctions against the space power in the wake of its actions in Ukraine. The ExoMars program was probably the greatest casualty, as the rover mission, already delayed and over budget, was finally on track for launch. (The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter launched in 2016, along with a landing demonstrator called Schiaparelli. Schiaparelli did not land safely, but the orbiter continues to study Mars from above today.)

Russia was to launch the rover on its Proton rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Roscosmos also built the Kazachok landing platform, which was not only supposed to deliver the rover to the planet’s surface, but also had its own scientific program at the landing site.

Vago said that while ESA can build most of its own landing platform, it will seek to obtain from NASA some technologies that it currently cannot produce at home.

“We don’t have the sort of descent engines that we could use,” Vago said. “We will need to use the jets that were used for delivering Curiosity or Perseverance, perhaps fewer engines but the same type. The other thing we need to replace are the radioactive heating units, which we also don’t have in Europe.”

Rebuilding the landing platform and reconfiguring the mission, however, will take time, and, if the mission is to go ahead, the launch is unlikely to take place before 2028, Vago said.

“We could launch in 2024 with Roscosmos on the Proton, but the way things are going geopolitically, I think this is becoming less and less probable,” he said. “2026 would be theoretically possible, but in practice, we think it would be very difficult to reconfigure ourselves and produce our own lander. So realistically, we will be looking at a launch in 2028, but even that requires some help from NASA.”

Launch windows for Mars missions open only every 26 months, when Earth and the Red Planet align properly.

NASA was ESA’s original partner in the ExoMars program, but the American agency withdrew in 2012 following budget cuts by the administration of President Barack Obama. At that time, the mission was rescued by Russia, which stepped in to fill NASA’s shoes.

The 2028 launch date would mean the ExoMars rover would get to Mars with a 10-year delay compared to the original plan. The mission was originally scheduled to lift off in 2018 but was held back due to problems with landing parachutes.

This delay would mean that ExoMars would likely not reach Mars long before the Sample Return Mission, on which ESA and NASA are set to cooperate. Astrobiologists, however, still see value in the ExoMars rover, as it is fitted with a 6-foot-long (2 meters) drill that will enable it to collect samples from deep underneath the planet’s surface. It is at those depths that scientists expect the likeliest survival of any traces of past or present Martian life.

Due to the absence of a magnetic field and the planet’s thin atmosphere, Mars is constantly battered by the solar wind, which effectively sterilizes its exposed surface. NASA’s Perseverance rover, which has already commenced collecting samples for a future return to Earth, has a much shorter drill, and therefore cannot reach as deep.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.