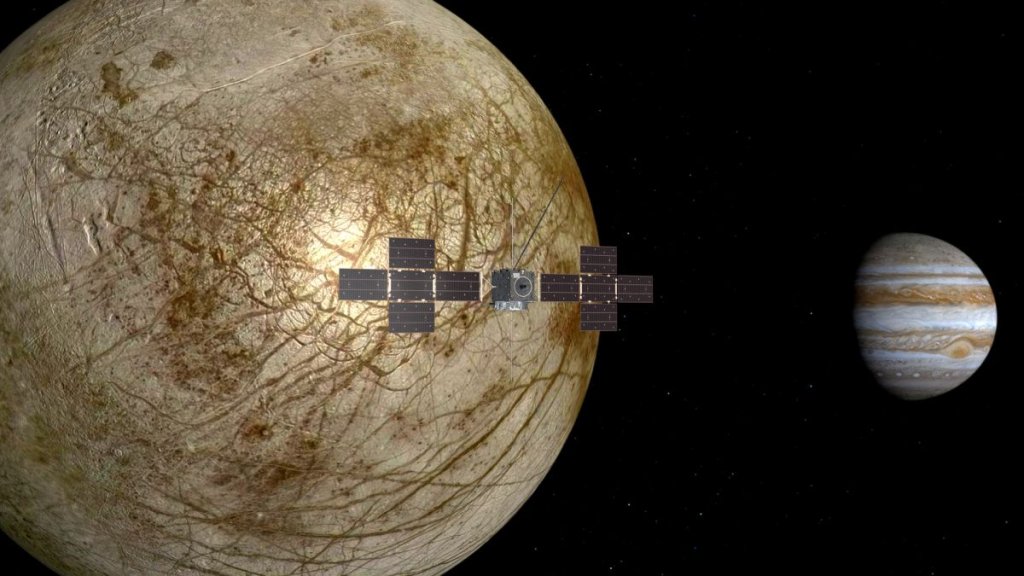

Europe’s JUICE mission will explore the Jupiter ocean moons Callisto, Europa and Ganymede. Here’s why they’re so weird (Image Credit: Space.com)

Next week, Europe will fly its first mission to the Jupiter system to explore the gas giant and three of its intriguing moons.

The European Space Agency (ESA)-led Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer spacecraft, or JUICE, will launch on Thursday (April 13) from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana. JUICE, packed with what ESA describes as (opens in new tab) “the most powerful payload ever flown to the outer solar system,” was recently cocooned inside the Ariane 5 rocket that will fly it to space.

This “means that we have seen the spacecraft for the last time ever,” ESA announced on the mission’s Twitter (opens in new tab) account on Wednesday (April 5). “And that we are one step closer to launch!”

Related: Europe’s flagship JUICE mission will study the Jupiter moons Europa, Callisto and Ganymede.

Shortly after taking off, JUICE will separate from the rocket, fan out its solar panels and kick start its 7.6-year-long cruise to the biggest planet in the solar system.

During its time in the Jovian system, JUICE’s main goal will be to study Jupiter and three of its largest moons: Europa, Callisto and Ganymede. The spacecraft does not have a lander, so it will not touch down on any of its targets, but it will fly by all moons multiple times to collect valuable data.

Between 2021 and 2034, JUICE will whisk by Europa only twice, skimming as low as 248 miles (400 kilometers) above the moon’s surface. The spacecraft will also whirl past Jupiter’s second-largest moon Callisto 21 times and conduct 12 flybys of Ganymede, according to the mission launch kit (opens in new tab).

In 2034, the spacecraft will enter orbit directly around Ganymede, making it the first moon other than Earth’s to have a spacecraft in its orbit. The mission will self-destruct a year later by crashing into Ganymede’s surface.

“[The moons] are special in the sense that we think they contain in their interiors vast oceans of liquid water, which is kind of fascinating,” Olivier Witasse, project scientist of the JUICE mission, told Space.com.

Mainly, JUICE will collect data to confirm the presence of such liquid water — crucial for life as we know it — below the surfaces of these moons, which was only hinted at by the Galileo mission back in the 1900s.

“I am really looking forward to seeing the findings after we arrive at [the] destination in 2031,” Witasse said. “I am just curious and patient (I have to [be]!)”

Related: The Galilean moons of Jupiter (photos)

Ganymede: A uniquely complicated world

Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, will be JUICE’s crucial scientific target, and for good reason.

Ganymede has a radius of 1,635 miles (2,631.2 km), which is just a bit smaller than that of Mars, and is 4.5 billion years old, placing it at the same age as its parent planet. Scientists think the moon formed from gas and dust left over from Jupiter’s formation, and the fact that it has been around since early in the solar system’s history makes it of immense scientific value.

Back in 1996, when the Galileo spacecraft ventured just 164 miles (264 km) above Ganymede’s surface, scientists were perplexed to discover (opens in new tab) its distinct planet-like magnetic field. To date, Ganymede is the only moon in the solar system known to boast a magnetic field of its own.

As Ganymede orbits Jupiter — which has its own massive magnetic field — from 665,000 miles (1 million km) away, the moon’s magnetic field is partly immersed in that of the gas giant. This interaction is complicated and unique and triggers bewildering phenomena on the moon, like the dancing auroras that “rock back and forth” in response to changes in Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Ganymede is also unique in hosting a surface that betrays its history for billions of years. In addition to having the largest impact crater among all solar system bodies, the moon is scarred with many craters, which dent 40% of its surface. The remaining 60% is filled with countless grooves that crisscross for thousands of miles.

Moreover, its subsurface ocean likely harbors more water than those of Earth, and scientists recently found that younger parts of the moon could have been formed by some flooding on its surface.

Together, this variety of surface features with equally diverse ages makes the moon a scientific hunting ground to learn about the history of the surface as well as its past and current geological activity.

Ganymede’s subsurface ocean is thought to be sandwiched between layers of ice, making the moon unlikely to host alien life, researchers say (because there’s likely not much interesting chemistry going on in that water). So the JUICE team is confident that ramming the spacecraft into Ganymede’s surface at the mission’s end won’t contaminate a life-hosting world. And this action will protect a different moon thought to be more friendly to life — Europa.

Related: The 6 most likely places for alien life in the solar system

Europa: ‘A cracked egg’

Europa may be the smallest of the four main moons of Jupiter, discovered by famed 17th century astronomer Galileo Galilei, but it is thought to be one of the best places for alien life to sprout.

Europa, unlike Ganymede, is relatively active, thanks to being closer to Jupiter. Due to that closeness, the gas giant has significant gravitational influence on Europa, as seen in the moon’s large tides that stretch and compress its frozen surface. At times, such activity cracks its youthful surface, which scientists think is only 20 million to 180 million years old, forming fractures and ridges that stretch for hundreds of miles and overlap to form their own intricate design.

Such features are seen as lines that “scratch” the moon’s surface, which scientists think may also host salt brought up from the underground ocean thought to be 40 to 100 miles (60 to 150 km) deep. This newly surfaced salt is bombarded by radiation, giving it a signature reddish-brown color, but the process that leads to this mysterious material is not well understood.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Europa is the occasional glimpse it provides of a global ocean hidden underneath its 15-mile-thick (20 km) icy surface. In the last few years, scientists think they have spotted evidence of sporadic water plumes blasting from the moon’s frigid surface. Such plumes, which may rise 120 miles (200 km) high, are thought to originate from the moon’s hidden ocean. However, scientists know little about the processes that drive these mechanisms on the oceanic world.

Europa’s frozen surface also has puddles of melted water, which scientists think could be “cozy habitats” for alien life. And its ocean is thought to be in contact with its rocky core, allowing a variety of complex chemistry to occur.

Related: Europa Clipper: A guide to NASA’s new astrobiology mission

The geologically dead Callisto

Jupiter’s second-largest moon Callisto, which is almost as big as Mercury and has 142 known craters marking its surface, is among the most battered moons in the solar system.

Unlike Europa’s surface, which is young thanks to the moon regularly recycling its surface, Callisto was once thought of as an “ugly duckling moon,” because of the dormancy on its 4.5 billion-year old surface.

Countless asteroid impacts have punctured Callisto’s surface, and the resulting craters have not changed much since they began accumulating 4.5 billion years ago. For example, Earth heals itself by recycling its surface continuously through plate tectonics. Callisto, on the other hand, is unable to do the same, so the moon was long thought to be a boring place to explore, let alone search for alien life.

Although there are no water plumes blasting from Callisto’s surface, scientists think the moon does host a salty ocean below its punctured surface. They found this thanks to data collected by the Galileo spacecraft, which put the moon back on the map of interesting worlds in the Jupiter system to explore.

A second mystery involving Callisto is its mysterious ability to continuously replenish its atmosphere, which is dominated by carbon dioxide but is apparently so thin that individual gas molecules are “literally drifting around without bumping into one another,” NASA’s Robert Carlson, who was the principal investigator of the Galileo spacecraft’s instruments, said at the time. Because the atmosphere is so weak, it easily disperses into space, but scientists do not yet know how the moon seems to time and again replace it.

Unsolved puzzles about Jupiter

You might think we know all that we need to about Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system. But scientists actually know very little about the evolution of the gas giant, whose thick atmosphere and absence of a solid surface leads to interesting but puzzling phenomena.

For example, Jupiter features strong auroras at its north and south poles. Scientists have been studying these Jovian lights for at least four decades, but they still don’t fully understand how they are created. The gas giant’s ability to host multiple life-friendly moons in its system is also one of the unsolved mysteries, one that the JUICE mission will try to unlock.

To carry out its explorations of the Jupiter system, JUICE carries with it a set of 10 complex and sensitive instruments. From a technical point of view, “building JUICE was not easy,” Witasse told Space.com. Preparing the spacecraft, which needs a lot of fuel to navigate, to be robust enough to face Jupiter’s strong and dangerous radiation is no small feat. Part of the mission’s development occurred during the pandemic, adding to the complications for the JUICE team.

“But all in all, we managed, and we are ready to launch,” Witasse said.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).