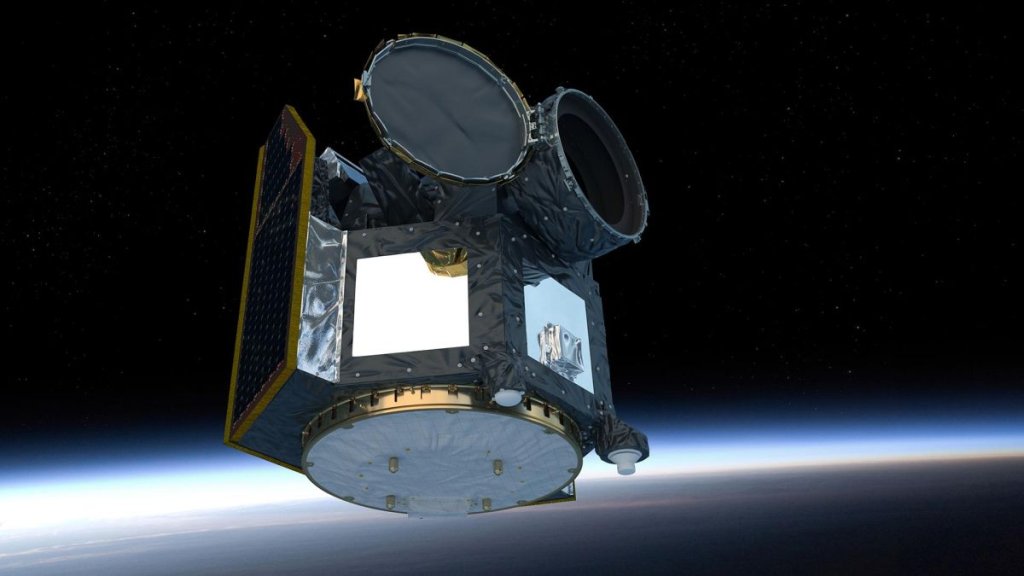

Europe’s exoplanet-hunting CHEOPS mission extended through 2026 (Image Credit: Space.com)

Europe’s CHEOPS spacecraft will continue investigating planets outside our solar system until at least 2026.

The European Space Agency (ESA) announced on March 9 that CHEOPS will continue its exoplanet-studying mission — which includes selecting “golden target” worlds for deeper investigation by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — for at least another three years, with the potential to extend this further until 2029.

Launched in December 2019 from ESA’s spaceport in French Guiana, CHEOPS (short for “Characterising Exoplanet Satellite”) is designed to study planets with sizes between that of Earth and of Neptune as they cross, or transit, the face of bright stars. But it has had impressive results with objects well outside this size range.

Related: 9 alien planet discoveries that were out of this world in 2022

The mission has taken exoplanet science beyond simple detection, to a deeper investigation of the atmospheres of these worlds as well as accurately measuring their size and shape. Exoplanets with interesting atmospheric compositions can then be passed to more powerful telescopes like JWST, meaning CHEOPS plays a key role in our hunt for planets that could potentially support life.

“In this respect, the mission has been extremely successful,” CHEOPS consortium head Willy Benz, a professor emeritus of astrophysics at the University of Bern in Switzerland, said in a statement (opens in new tab). “The precision of CHEOPS has exceeded all expectations and has allowed us to determine properties of several of the most interesting exoplanets.”

An example of CHEOPS’ contribution to science was the discovery that the gas giant WASP-103 b, first spotted in 2014, has a distended, flattened shape similar to that of a rugby ball. The ESA spacecraft made this determination in 2021 by examining the brightness drop the planet causes as it transits the face of its star.

The compressed shape of WASP-103 b is believed to be the result of tidal interactions with its parent star, and the revelation marked the first time the shape of an exoplanet had been so well defined.

CHEOPS has also had an impact closer to home. Just this year, observations from the spacecraft were used to discover that Quaoar, a dwarf planet in our solar system, is surrounded by a ring of dust. The ring is exceptional because it is farther out from its parent body than any ring previously discovered, challenging theories of how such structures form.

The primary science mission of CHEOPS was only initially planned to last for three and a half years, until September 2023, but ESA said the spacecraft is in excellent health after over three years in Earth orbit.

During this time, CHEOPS has coped admirably with the rigors of space, such as the bombardment of cosmic rays and high-energy radiation, while on Earth its operating team worked to keep the spacecraft operational through the global pandemic.

There are many exciting observing opportunities left for CHEOPS. For example, the mission team hopes to use the spacecraft to discover the first exomoon — a moon orbiting a planet outside the solar system. Exomoons are tough to spot due to their comparatively small size and thus the faint signature they cause as they pass in front of a star, but the CHEOPS team thinks the spacecraft is sensitive enough to make such a detection.

“We have only scratched the surface of the capabilities of CHEOPS. There is much more science that can be done with the satellite, and we look forward to exploring it during the extension,” Benz said. “Scientists are eager to find out what surprising results CHEOPS will bring next; what is sure now is that CHEOPS will continue to make new discoveries for years to come.”

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).