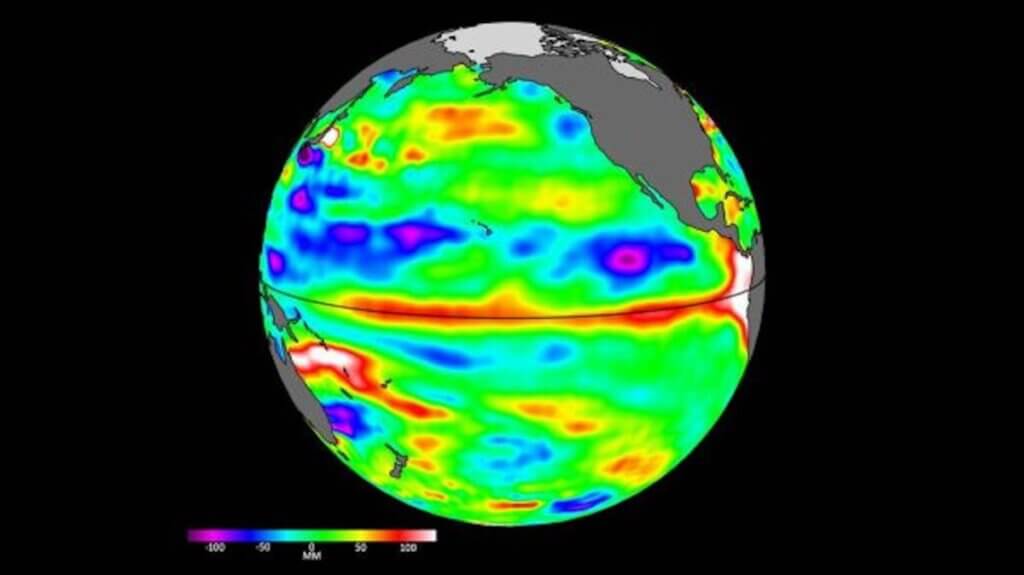

El Nino is officially here and may cause temperature spikes and major weather events, scientists warn (Image Credit: Space.com)

For the first time in 7 years, El Niño conditions have developed in the Tropical Pacific, prompting expert to urge that preparation for extreme weather events will be necessary to protect lives and safeguard livelihoods.

El Niño is a naturally occurring climate phenomenon that is connected to ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The United Nations World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has warned that El Niño conditions signal the possibility of a surge in global temperatures and disruptive weather. The WMO added that there is a 90% probability El Niño conditions will continue into the latter half of 2023 and until the end of the year.

“The onset of El Niño will greatly increase the likelihood of breaking temperature records and triggering more extreme heat in many parts of the world and in the ocean,” WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement.

Related: Climate change hits Antarctica hard, sparking concerns about irreversible tipping point

“The declaration of an El Niño by WMO is the signal to governments around the world to mobilize preparations to limit the impacts on our health, our ecosystems, and our economies,” Taalas added. “Early warnings and anticipatory action of extreme weather events associated with this major climate phenomenon are vital to saving lives and livelihoods.”

The last major El Niño event occurred in 2016, a year that remains the joint hottest 12 months on record, tied with 2020. 2016’s status as a record hot year due to a “double whammy” of a powerful El Niño event and the effect of greenhouse gases on climate change.

According to the WMO, the 8-year period containing 2016 and 2023 has been the hottest since record-keeping began in 1880.

El Niño is a “wake-up” call about climate change targets

According to the Met Office in the U.K., El Niño conditions are declared when sea temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific rise half a degree above the long-term average. This occurs on average every 2 to 7 years in bouts that last between 9 and 12 months.

Despite the fact that El Niño is a natural phenomenon, it can’t be viewed in isolation from human-driven (anthropogenic) climate change.

In a report published in May this year, the WMO was already predicting a 98% chance that one of the next five years, and this five-year period as a whole, would be a record-breaker in terms of global temperature, displacing 2016 and 2020 from the top spot as the warmest years on record.

The report also suggested there is a 66% possibility that the annual average near-surface global temperature will, at some point between 2023 and 2027, reach 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels for at least a year.

“This is not to say that in the next five years, we would exceed the 1.5°C level specified in the Paris Agreement because that agreement refers to long-term warming over many years,” WMO Director of Climate Services Chris Hewitt said. “However, it is yet another wake-up call, or an early warning, that we are not yet going in the right direction to limit the warming to within the targets set in Paris in 2015 designed to substantially reduce the impacts of climate change.”

El Niño and La Niña in 2023

El Niño events are usually linked to an increase in rainfall and even flooding in parts of the southern U.S., southern South America, the Horn of Africa and Central Asia.

On the flip side of this, the phenomenon is believed to lead to severe droughts across Central America, northern South America, Australia, Indonesia, and parts of southern Asia.

The effects of El Niño are generally considered to be the opposite of those of another climate-driving event, La Niña, periods of cooler than average sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific. The last La Niña ended in March 2023.

A month prior to the end of La Niña, average sea surface temperature anomalies in the central-eastern equatorial Pacific rose from nearly half a degree below average in February to around almost a full degree above average in mid-June. This, coupled with atmospheric observations, strongly hinted at the onset of El Niño conditions.

A fully established connection between ocean and atmosphere temperatures could take another month to fully couple in the tropical Pacific.

“As warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures are generally predicted over oceanic regions, they contribute to the widespread prediction of above-normal temperatures over land areas,” the WMO recently said in its regular Global Seasonal Climate Update (GSCU) for July, August and September. “Without exception, positive temperature anomalies are expected over all land areas in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere.”

Rainfall conditions for these three months are forecast to be in line with what would be expected for an El Niño period. The WMO said that the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) will now monitor El Niño conditions and their impacts on rainfall and temperature on national and local levels. In addition to this, the WMO said it will issue updates on El Niño over the coming months as needed.