Egg-shaped galaxies may be aligned to the black holes at their hearts, astronomers find (Image Credit: Space.com)

Black holes don’t have many identifying features. They come in one color (black) and one shape (spherical).

The main difference between black holes is mass: some weigh about as much as a star like our Sun, while others weigh around a million times more. Stellar-mass black holes can be found anywhere in a galaxy, but the really big ones (known as supermassive black holes) are found in the cores of galaxies.

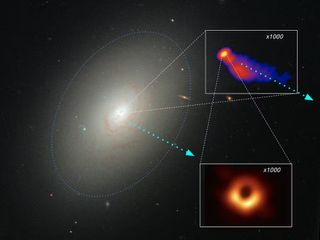

These supermassive behemoths are still quite tiny when seen in cosmic perspective, typically containing only around 1% of their host galaxy’s mass and extending only to a millionth of its width.

However, as we have just discovered, there is a surprising link between what goes on near the black hole and the shape of the entire galaxy that surrounds it. Our results are published in Nature Astronomy.

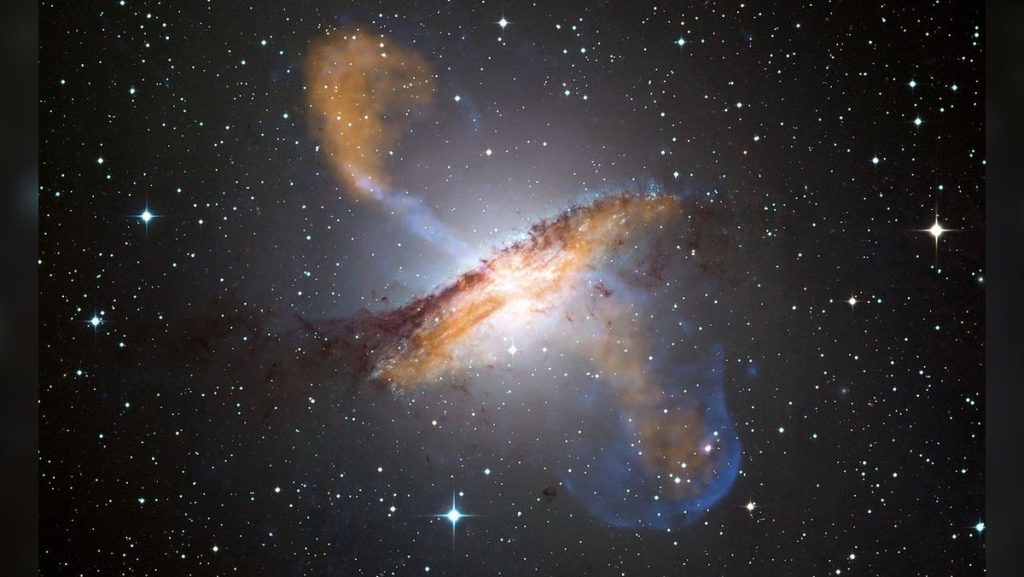

Related: Stunning image shows dark tendrils masking giant Centaurus A galaxy near Earth

When black holes light up

Supermassive black holes are fairly rare. Our Milky Way galaxy has one at its centre (named Sagittarius A*), and many other galaxies also seem to host a single supermassive black hole at their core.

Under the right circumstances, dust and gas falling into these galactic cores can form a disk of hot material around the black hole. This “accretion disk” in turn generates a super-heated jet of charged particles that are ejected from the black hole at mind-boggling velocities, close to the speed of light.

When a supermassive black hole lights up like this, we call it a quasar.

How to watch a quasar

To get a good look at quasar jets, astronomers often use radio telescopes. In fact, we sometimes combine observations from multiple radio telescopes located in different parts of the world.

Using a technique called very long baseline interferometry, we can in effect make a single telescope the size of the entire Earth. This massive eye is much better at resolving fine detail than any individual telescope.

As a result, we can not only see objects and structures much smaller than we can with the naked eye, we can do better than the James Webb Space Telescope.

When black holes light up

Supermassive black holes are fairly rare. Our Milky Way galaxy has one at its centre (named Sagittarius A*), and many other galaxies also seem to host a single supermassive black hole at their core.

Under the right circumstances, dust and gas falling into these galactic cores can form a disk of hot material around the black hole. This “accretion disk” in turn generates a super-heated jet of charged particles that are ejected from the black hole at mind-boggling velocities, close to the speed of light.

When a supermassive black hole lights up like this, we call it a quasar.

How to watch a quasar

To get a good look at quasar jets, astronomers often use radio telescopes. In fact, we sometimes combine observations from multiple radio telescopes located in different parts of the world.

Using a technique called very long baseline interferometry, we can in effect make a single telescope the size of the entire Earth. This massive eye is much better at resolving fine detail than any individual telescope.

As a result, we can not only see objects and structures much smaller than we can with the naked eye, we can do better than the James Webb Space Telescope.