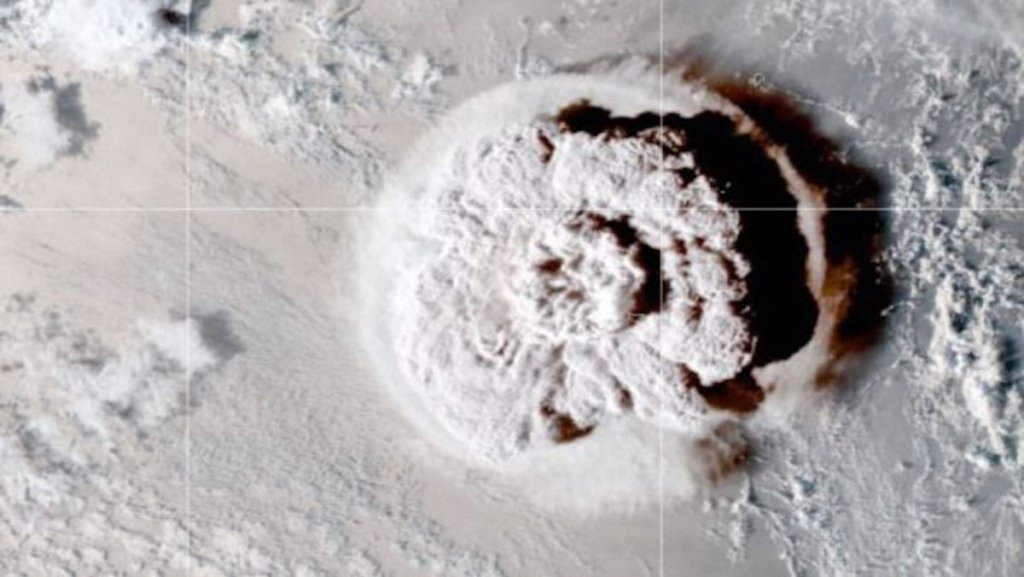

Did the Tonga undersea volcano eruption cause this year’s extreme heat? (Image Credit: Space.com)

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption in January 2022 was one of the biggest volcanic eruptions in recorded history. Detonating underwater with the force of 100 Hiroshima bombs, the blast sent millions of tons of water vapor high into the atmosphere.

Some commentators have speculated in recent weeks that the volcano is to blame for searing summer temperatures and are even using the volcano to cast doubt on the role humans are playing in climate change, as reported by The Hill.

So is the gigantic eruption responsible for this summer’s sweltering conditions?

“The short answer is no,” Gloria Manney, a senior research scientist at NorthWest Research Associates and New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, and Luis Millán, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Live Science together in an email.

“Even though El Niño has made the global temperature higher and the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption might have affected some regions for a short time, the main culprit is climate change,” they said.

And numerous studies show that the massive eruption isn’t causing this climate change — human activites such as the burning of fossil fuels are the driving factor.

Related: Tonga eruption’s towering plume was the tallest in recorded history

Why are some people blaming the volcano?

Massive volcanic eruptions usually reduce temperatures because they spit out vast amounts of sulfur dioxide, which form sulfate aerosols that can reflect sunlight back into space and cool Earth’s surface temporarily, the researchers explained. But the Tonga eruption had another effect because it occurred underwater.

“The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption is peculiar because, in addition to causing the largest increase in stratospheric aerosol in decades, it also injected vast amounts of water vapor into the stratosphere,” Manney and Millán said.

Water vapor is a natural greenhouse gas that absorbs solar radiation and traps heat in the atmosphere. The aerosol and water vapor impact the climate system in opposing ways, but several studies have proposed that, due to its larger and more persistent water vapor plume, the eruption could have a temporary net surface warming effect, Manney and Millán said.

A study published in the journal Nature Climate Change in January estimated that the eruption increased the water vapor content of the stratosphere by around 10% to 15% — the biggest increase scientists have ever documented. Using a model, they calculated that the water vapor could increase the average global temperature by up to 0.063 degrees Fahrenheit (0.035 degrees Celsius), Eos magazine reported in March.

Some commentators linked the eruption to warming because of this finding, and other studies suggesting a potential warming effect, but researchers involved in these studies have been clear that the volcano isn’t a major factor in our wild weather.

“It’s probably fair to say that the influence of [the volcano] on this year’s extremes is quite small,” Stuart Jenkins, a climate scientist and postdoctoral researcher at Oxford University in the U.K. and lead author of the January study, told The Hill.

The bigger climate picture

Earth’s warming trend predates the eruption. July may have been the hottest month on record for global temperatures, but the five hottest Julys have all been recorded in the past five years, according to NASA.

Manney and Millán said that more detailed models are needed to reveal how much impact the eruption had on global temperatures relative to burning fossil fuels and the El Niño, but the effects are expected to be much smaller than those from burning fossil fuels.

“Last July’s record-breaking global temperatures are just a preview of what may happen if we do not take more bold and ambitious climate action,” they said.

In May, the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization warned there’s a 66% chance that annual mean global surface temperatures will likely cross a dangerous 2.6 F (1.5 C) warming threshold at some point in the next five years.

At 2.6 F of warming, extreme heat waves will become more widespread, with higher chances of droughts and reduced water availability, according to NASA.

Going above 2.6 F could trigger climate tipping points such as the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets.