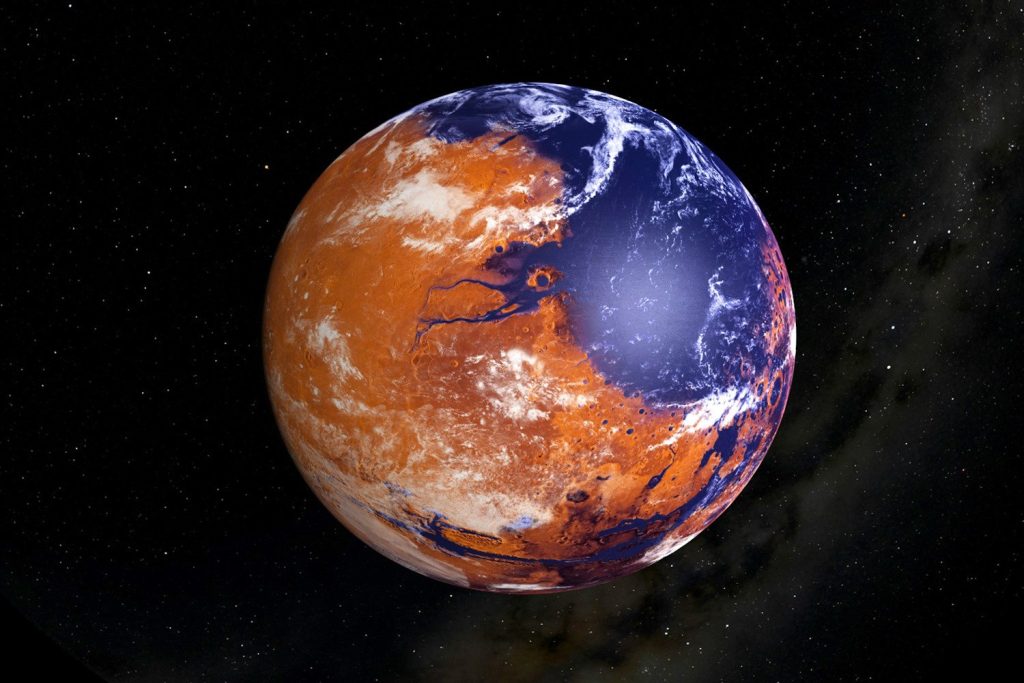

Curiosity Rover Finds Clues to How Mars Became a Lifeless Wasteland (Image Credit: Gizmodo-com)

NASA’s Curiosity rover has added a new wrinkle to the theory that the surface of Mars was once hospitable to alien life. New chemical analysis of Martian dirt hints at eras in the planet’s past where the conditions necessary for life may have been met, but only for relatively short periods of time. The very processes that led to elements vital to life being present in Martian soil, may also have led to the waterless conditions currently present.

The trundling robot, which has been exploring Mars’ Gale Crater since 2012, analyzed soil and rock samples from the planet’s surface as part of an effort to find carbon-rich minerals. Carbon is often seen as being vital to life, as its ability to form strong bonds with a host of other atoms makes molecules like DNA and RNA possible. What the rover found suggests that Mars is not only a hostile environment today, but that any periods when the planet could have been habitable may have been brief. However, as the saying goes, life finds a way. More research is needed to determine if microbes might have thrived in more hospitable conditions underground.

NASA’s rovers have found evidence that Mars once had lots of organic compounds rich in the carbon-bearing minerals known as carbonates, and a meteorite with Martian origins has been found to contain carbon, as well. To figure out which isotopes of carbon and oxygen are present in those carbonates, the Curiosity team turned to the rover’s Sample Analysis at Mars instruments. The equipment heats collected samples to over 1,650 degrees Fahrenheit (899 Celsius) and then uses a laser spectrometer to analyze the gasses that are produced.

When the data was transmitted back to Earth, NASA scientists determined it contained higher levels of certain heavy carbon and oxygen isotopes than had previously been found in Martian samples.

Both elements are vital to the carbon cycle, in which carbon goes through different forms, thanks to processes such as photosynthesis. The carbon cycle is an integral part of life here on Earth, but the researchers found the proportion of heavier isotopes of carbon and oxygen in the samples was far higher than what’s found on Earth.

As the geologists explained in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, there are actually two ways the soil could have become home to this particular mix of isotopes. In one, Mars underwent an alternating series of wet and dry periods. During the latter, water would have evaporated, bringing the lighter versions of those elements up into the atmosphere with it, and leaving the heavier isotopes behind. Because liquid water didn’t last long, there were only brief periods where the planet could have been home to life.

In the other, the carbonates formed in very salty water that was exposed to extreme cold. Not a great place to be if you’re alive, even if you’re an amoeba.

“These formation mechanisms represent two different climate regimes that may present different habitability scenarios,” said Jennifer Stern, a space scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who worked on the paper, in a statement. “Wet-dry cycling would indicate alternation between more-habitable and less-habitable environments, while cryogenic temperatures in the mid-latitudes of Mars would indicate a less-habitable environment where most water is locked up in ice and not available for chemistry or biology, and what is there is extremely salty and unpleasant for life.”

While it might seem like a setback for the search for Martian life, that’s not necessarily the case. David Burtt, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA who led the study, said that while the findings point to a history of extreme evaporation, life could still have found refuge in underground biomes. He also didn’t rule out the possibility of an even more ancient atmosphere, more friendly to life, that could have existed before these particular carbonates formed, or that different climate conditions could have existed in other areas of Mars.

The search for life on Mars has been something of a mixed bag. While there have been compelling signs, it would be a stretch to call any of the evidence conclusive. The hunt continues as Curiosity, and its comrade Perseverance, continue their slow trek across the Martian terrain. NASA hopes to send a crewed mission to Mars in the 2030s or 2040s, and, should that happen, it could be the first time living, breathing entities ever take in the harsh vistas.