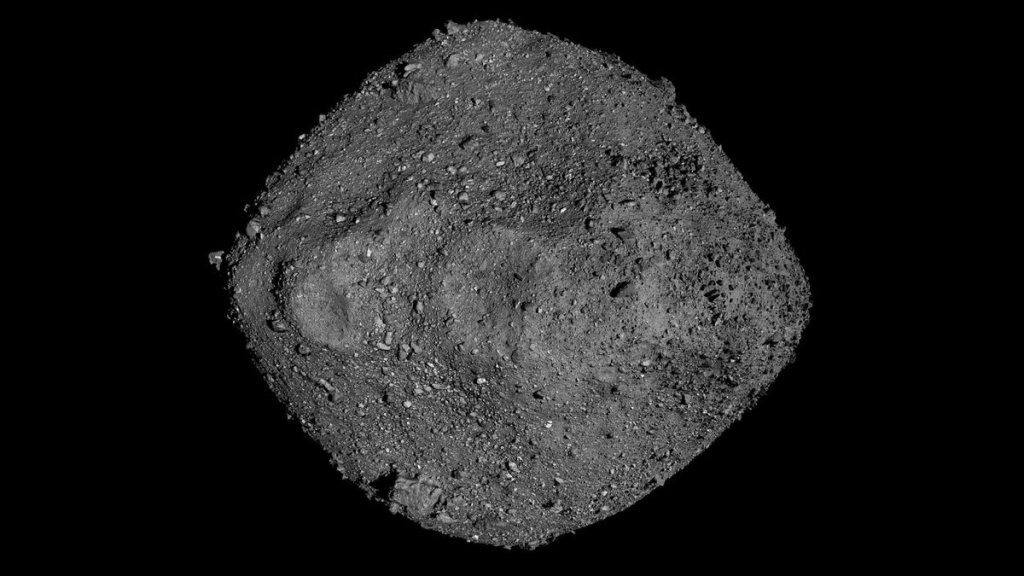

Could we defend Earth against a ‘rubble pile’ asteroid? (Image Credit: Space.com)

The last few years saw a spate of up-close encounters and smash-ups with various asteroids. Interestingly, the rubble pile composition of asteroids has been surprising in several cases.

Asteroid probes from several nations have found not solid objects, but countless pieces of gravel and boulders loosely bound together by the object’s own small gravity field.

Of late, it was the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission that left bite marks on asteroid Bennu, snagging and bagging bits and pieces of that rubble pile, then parachuting those collectibles into Utah last September. Similarly, Japan’s two Hayabusa missions hauled back to Earth specimens of the rubble piles, asteroid Itokawa (2010) and asteroid Ryugu (2020).

This revelation is drifting through the planetary defense community. How do we deal with incoming space rocks that are double trouble: Bad for Earth, but also tough to deal with due to their makeup?

Related: Rubble-pile asteroids are ‘giant space cushions’ that live forever

Go-to technique

The smashing success of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, saw humankind ace its first mission to purposely move a celestial object. After ten months of journey, DART’s kinetic, spot-on thumping of asteroid Dimorphos occurred in September 2022, altering the asteroid’s orbit period around its tiny celestial companion, asteroid Didymos.

“Pre-impact projections estimated a range of possible deflections, and the post-impact observations revealed a significant deflection of the target asteroid at the high-end of the pre-impact models,” reports NASA, citing the DART outcome as “a promising result for applying the technique in the future if needed.”

The kinetic impact method showcased by DART has been the “go-to technique of choice” if trying to deflect an asteroid headed toward Earth, said John Brophy, an Engineering Fellow at Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“They hit it very close to the center of mass. It was a good shot,” Brophy told Space.com.

On the other hand, asteroid rubble piles seemingly give rise to that Forrest Gump axiom that life is like a box of chocolates: “You never know what you’re gonna get.”

“If you hit it hard enough to deflect it, in a single impact, you are very likely to disrupt it. And disrupt it means blast it apart,” Brophy said. What takes place next is “a chaotic process with uncertain results,” he said.

Controlled process

Having kinetic impactors repeatedly strike a target in a kinder and gentler fashion is one idea, but that approach also presents challenges.

Brophy was a study lead for a new planetary defense idea known as ion beam deflection. “You direct the ion beam to impact the asteroid, along its velocity vector. With ion beam deflection you spread that power out over months or maybe even a year or two,” he said.

Using this ion beam concept has several benefits, Brophy added. For one, it is a very controlled process. It also works on rubble piles and doesn’t care what the strength of the object is or its make-up or how the space rock is rotating.

Ion beam deflection “is a potentially attractive approach that can help mitigate the issues of deflecting rubble piles,” Brophy said. Then of course, he noted, there’s use of a nuclear device for deflection purposes, but that’s seen by many as a technique of last resort.

Read more: 8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons, paint and Bruce Willis

Big dog

Ed Lu is executive director of the Asteroid Institute, which is a program of the B612 Foundation. As a NASA Astronaut, he flew three space missions, logging 206 days in Earth orbit, to help construct and live aboard the International Space Station.

Lu is also a co-inventor of the Gravity Tractor, a controllable means of deflecting asteroids, using only a spacecraft’s gravitational field to convey the required impulse. Testing out the concept in space in experimental mode is under study, he said.

From a planetary defense standpoint, Lu has long been saying that deflection is not the difficult issue. “It has never been the hard part. It has always been finding, tracking, and getting a complete catalog and know when something is going to hit,” he told Space.com.

The big asteroid news, Lu said, is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, currently under construction on Cerro Pachón in Chile. It is expected to excel at spotting new asteroids as the facility will monitor large areas of the sky every night and can detect very dim moving objects.

“It is the really the big dog and can make most of those discoveries over the next few years. The first several years of its operation are the most prolific. That’s when everything is easy pickings,” Lu said.

Governance issues

A recent public poll said keeping an eye on Earth-bruising trajectories of asteroids should be NASA’s top priority.

“Monitoring asteroids that could potentially hit the Earth ranks at the top of the public’s priority list for NASA. Monitoring the planet’s climate system also ranks highly as a priority for NASA. But relatively few Americans say it should be a top priority to send human astronauts to the moon or Mars,” reported a July 20 Pew Research Center “fact tank” finding.

Technologically dealing with rubble piles is one thing, but more work also appears needed to hash out the political and sociological aspects of fending off asteroids that have cross-hairs on Earth.

Nikola Schmidt works as a senior researcher and is head of the Center for Governance of Emerging Technologies at the Institute of International Relations in Prague. He is author of a recent look at 30 years of planetary defense governance.

“The problem is that we do not know what is under the surface of the rubble piles,” Schmidt told Space.com. “There could be hollows inside or spaces between bigger rocks might be fully filled by regolith. This is something we do not know and can cause significantly different effects. So yes, the structure is a problem and about 70-80% of the asteroid population is believed to consist of rubble piles,” he said.

Security regimes

In Schmidt’s paper appearing in the January issue of the journal Acta Astronautica, he observes that today, we are not in a situation in which the Earth would be smoothly defended.

“This is not to say that the United Nnations bodies, expert entities and the whole planetary defense scientific community are not communicating and sharing information.” They are, Schmidt quickly adds, but the fact that states want to keep decision-making in their own hands runs counter to being prepared on a planetary level and avoiding unnecessary international discussions in the event of of an imminent threat.

“This is why states have developed international cooperation in the form of multilateral security regimes,” Schmidt said. “They lay down procedures for decision-making that will not be changed due to elections in particular states and can provide security assurance to all for unequal contribution, which is crucial for the security of small states and legitimacy of action for powerful states — each can contribute what they can, but all enjoy same security from the cooperation.”

Cosmopolitan responsibility

Schmidt told Space.com that he has been arguing for years that planetary defense is about cosmopolitan responsibility, “which is constituted by the ongoing production of new scientific knowledge about asteroids and their orbits. The knowledge changes our perception of the world around us that traverses the borders of nation-states and their power to do anything about it. Therefore, states must find a way to cooperate or they fail to fulfill their principal reason of existence — provide security to the citizens.”

Cosmopolitan is also not the kind of language to be sold to the public, Schmidt concludes, “but planetary defense is rearticulating social contract as anything else in the continuously transforming society.”