Cooperation on the moon: Are the Artemis Accords enough? (Image Credit: Space.com)

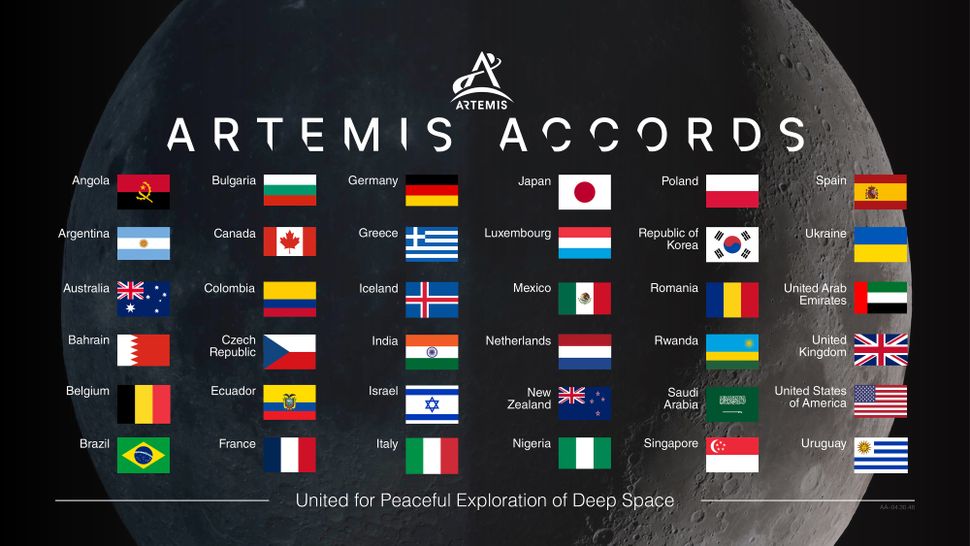

In February, Uruguay became the 36th country to sign the Artemis Accords, a set of non-binding principles to spawn responsible actions on the moon.

The Accords were established in 2020, formulated by NASA, in coordination with the U.S. Department of State. Since that time, there’s been a steady pace of countries inking the Artemis Accords, a set of principles crafted to guide cooperation in space exploration among nations, including those participating in NASA’s Artemis Program to “re-boot” the moon.

The underlying premise of the Accords is promoting “best practices and norms of responsible behavior” when it comes to lunar exploration. But that’s a tall order given the tumult of the times. Space.com pulsed specialists as to how the Accords are playing globally, as well as within the eagle-eye, legal-beagle community.

Related: Artemis Accords: Why the international moon exploration framework matters

High stakes call for basic norms

“Make no mistake. Humanity is once again in a space race,” said space lawyer Michelle Hanlon, a “Permanent Observer” of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

Hanlon is executive director of the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi School of Law, as well as co-founder of For All Moonkind.

As for a 21st century space race, Hanlon told Space.com that this time around the stakes are much higher than they were when it was just the United States and the former Soviet Union trying to outshine the other.

“Many talk about the access to resources in the moon and beyond, but it is even bigger than that. We are talking about the governance framework that will provide the foundation for all space activity for decades to come,” Hanlon said.

The Artemis Accords are not a binding Treaty, said Hanlon, they are a political commitment.

“It says that we, the undersigned, agree generally on some important aspects of space exploration. It also says that we have much more to negotiate and agree upon, Hanlon said.

“The laws and norms that will be applied to space activities cannot be formed in a vacuum; so instead, we find baselines — the Accords — and agree that these will be a starting point,” the space lawyer stated.

There are those that suggest the Accords are in competition with China’s stated ambition to plant on the moon an International Lunar Research Station, or ILRS. “And in a sense they are,” Hanlon observed.

“It’s like picking teams for the pick-up soccer game,” Hanlon added. “But there is no reason, from a policy perspective, that the ILRS parties and the Artemis parties cannot agree on basic norms for space.”

It is Hanlon’s view that “any nation that wants a say in the future of humanity should join the Accords.”

Power rivals

John Hickman is a professor of international affairs at Berry College in Mount Berry, Georgia. He said that Washington, D.C.’s Artemis Accords cannot be understood as international politics in isolation from Beijing’s ILRS venture.

“Dominated by great power rivals the USA and China, both are coalitions of space faring states engaged in competition for the moon and cislunar space,” Hickman told Space.com.

Hickman said that the Artemis Accords represent “a diplomatic effort to ‘paper over’ flaws” in the United Nations 1967 Outer Space Treaty. He particularly calls out the non-appropriation language, “which is subject to different interpretations.”

Hickman has explained what he views as the unimpressive nature of the Artemis Accords, doing so a few years ago in an opinion piece for the journal E-International Relations.

The Artemis Accords “are likely to be transient lunar phenomenon, of the political sort,” Hickman wrote in the op-ed.

Furthermore, Hickman concluded, the United States can get away with the Artemis Accords “only so long as it absorbs some of the business risk of the sketchy international legality of extraterrestrial mining projects, and if crucially neither China nor Russia decide to renounce the 1967 Outer Space Treaty by annexing their own slices of lunar territory.”

An imperfect

“I think the Artemis Accords are a contribution to the progressive development of international space law,” said Rossana Deplano, an associate professor at the University of Leicester Law School and co-director of the Centre for European Law and Internationalisation in the United Kingdom.

“My analysis of the Artemis Accords, in particular, suggests that they are fully compliant with the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which is unanimously regarded as ‘the constitution for outer space.'”

Deplano said that the Artemis Accords are only one of the possible ways in which space actors can ensure compliance with the Outer Space Treaty.

“The forthcoming Sino-Russian International Lunar Research Station may offer a different way of conducting scientific research on the moon, including a different way of implementing the provisions of the Outer Space Treaty,” said Deplano.

However, there are two imperfections of the Artemis Accords, as explained in Deplano’s review in the journal International & Comparative Law Quarterly.

Those flaws in the Accords, Deplano said, are that they do not explicitly take a position on the issue of benefit sharing. Also, they do not refer to relevant mechanisms for the settlement of space disputes.

Nevertheless, in general, Deplano said, the Artemis Accords promote transparency and due diligence in scientific space missions.

Unavoidable opposition

“Since their announcement, the Artemis Accords have proven to be highly successful,” said Almudena Azcárate Ortega, a researcher in space security within the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) in Geneva, Switzerland.

The support for the Accords is significant, despite their non-legally binding nature, Ortega told Space.com.

Moreover, the willingness of States to adopt them can serve as an indicator of State practice, Ortega added, which can contribute to the interpretation of general principles enshrined in the Outer Space Treaty “that have been very unclear and hotly debated in the space law and policy multilateral sphere.”

Ortega said that the Artemis Accords has sparked States speaking against them, namely two of the other great space powers: Russia and China.

“Both countries have expressed concerns that the Artemis Program is too U.S.-centric, and the likelihood of either of these countries signing the Accords is most likely none,” Ortega advised.

This “unavoidable opposition” is both due to substantive issues, Ortega said, but also due to the current geopolitical climate.

That hot-under-the-collar climate affects any measure or initiative presented to the international community, Ortega said, “and the Artemis Accords are no exception to this.”